Good Preservation vs. Bad Preservation

A supporter of development makes a case for why landmarking and preservation is really good but can be misused.

We’ve all seen it before. First, a housing project is proposed somewhere and then a group of people declare this somewhere a historic site and landmark it. It happens regularly throughout the country, from landmarking houses, gas stations, parking lots, murals, parks, neighborhoods and even vantage points. It’s negatively polarized many development enthusiasts against historic preservation and landmarking. This bothers me because I love spending my weekends reading about landmarks, but I also support more development. I don’t think landmarking nationally significantly impedes development, but it does occur more frequently in older and major cities.

Any conversation about historic preservation and landmarking must acknowledge the following: what qualifies as historic is 100% subjective. Nobody 100% agrees on how best to honor or display the history of something. I can’t possibly declare strict criteria, but I can articulate what I believe people broadly value about preservation and how to best go about honoring that.

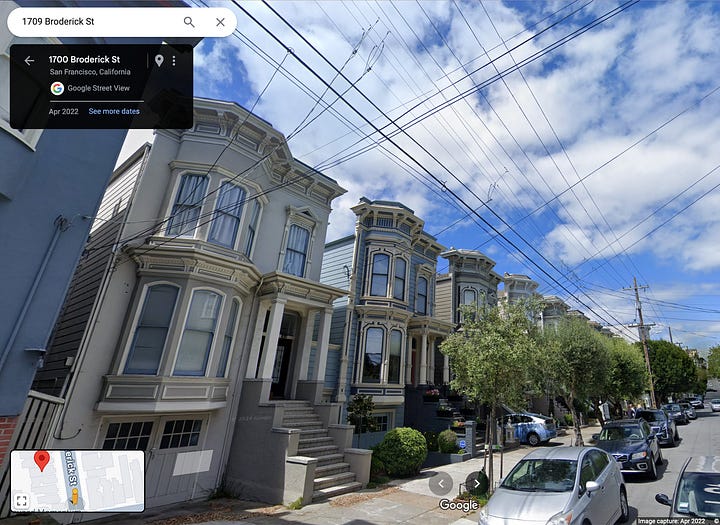

Many U.S. cities have landmarking criteria that make properties older than 40 years old eligible for preservation. I don’t believe something being old makes it worthy of preservation or that newer things should be ineligible from landmarking. I’m also wary of landmarking or implicitly protecting styles of old houses. While I admire Boston rowhouses, Brooklyn Brownstones or Queen Anne Victorians in San Francisco, the common examples of these are mass-produced market housing of an older era. These homes are usually not specially designed houses by top architects or artisans of their time, but are boxes built en-masse by real estate developers plastering industrial-cut ornaments onto front-facing facades — hardly different than glossy modern construction projects today.

San Francisco landmarked an entire wealthy neighborhood to make it immune from a state duplex law, angering the YIMBYs. But I diverged with both the city and pro-housing activists on this historic status. The public art of Saint Francis Wood (the fountains, pillars, landscaping, entryways and the tract office) do exemplify a very rare style created by top architects that warrants preservation and is clearly eye-popping. However, most of the homes built there are dime-a-dozen catalog mansions found in other wealthy subdivisions of the era, or upscale but not unique designs by elite architects. The timing and intent of the landmarking were abusive.

Mass production of something doesn’t disqualify landmarking, but it discounts the uniqueness of that something being landmarked and lends more to just valuing old things. Victorian houses are pretty, but Victorians were common architecture for the 1800s and can be found in nearly every old town in America. Often of much better quality and craftsmanship than the common ones in San Francisco which are mostly plain boxes with fancy but mostly identical mass-produced facades. If people want to argue they just think the homes look better than modern architecture, by all means, but I would oppose its preservation as historically important. Even the famous Parisian Haussmann buildings are essentially the same style copy-and-pasted endlessly with very little uniqueness about them.

I do validate landmarking places based on the people or actions and not just the aesthetic of a building. Gettysburg, The Haymarket Square, Spanish Missions, slave plantations, Lorraine Motel, you name it, are worthy landmarks. Even the small stuff like the first barn in a town or an activist’s home can warrant a landmark. But it becomes debatable whether conveying the history with a preserved presentation outweights the social gains of a project and a historical plaque.

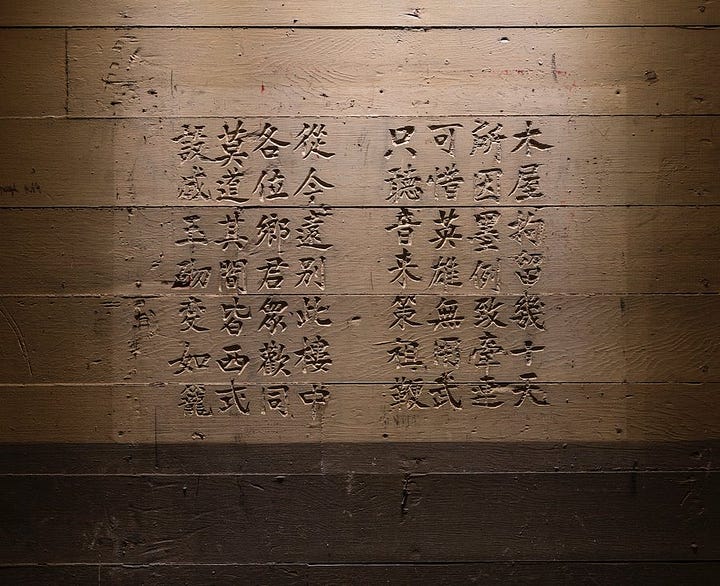

Take People’s Park in Berkeley, which was a very controversial example of how to convey historic importance. The fundamental tension between pro- and anti-housing development sides is —or was — that locals felt the park as it had existed did not honor the history of the anti-war and free speech protest of 1969, versus protesters who thought the act of protesting and rioting for the park was itself conveying its history. I noticed that most passersby learned its history from the eye-catching mural across the street from the park. I’d argue the enduring legacy of the 1969 protest was the free speech that came after it which moved student protests from the park to the Berkeley campus. That legacy isn’t erased from history even when the housing is finished and the park comes back in shruken form.

For a not-controversial example of landmarking, the Cable Cars in San Francisco are historic preservation at its finest because they’re beautiful, have a practical use, communicate history yet impact the present, are rare, and their historical value is notable beyond a handful of historians. Landmarking at its worst was probably this controversial house in my neighborhood that made national news for my famous neighbor attempting to preserve it. It hits all my boxes for what’s unworthy of preservation. The house is ugly, the architecture isn’t novel, its significance cannot be conveyed for people today, it wasn’t even recognized beyond a small clique of local historians, and the landmarking disproportionately depended on it simply being old.

I recall when activists in Berkeley attempted to landmark a view of the Golden Gate Bridge at a very particular vantage point to block a mid-rise apartment. This case was very transparently bad faith but even in Japan, a developer blocking a view of Mount Fuji was forced to tear the condos down! On landmarking views, I believe we need to tread carefully and ensure there is widespread consensus about the significance of that view. Too often these view preservations are unusually broad, the vantage points beneficial to a very small group of wealthy people, and fundamentally change a city that large portions of a city don’t agree with. Such as the fight over 4-story housing for farm workers near a California beach.

When historic preservation devolves into a niche club declaring the significance of places over the political or social will of the electorate as a whole, that’s when it goes awry. Especially when landmarking prevents more landmarks. The Transamerica Pyramid, Coit Tower, hell even the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco were derided for their appearance at ruining a historic view — until they were complete and became the historic view.

There’s history behind every brick in every city. I went to Los Angeles last week and went on a Dingbat Tour! They’re one of the most derided apartment styles in history, but to me is rich with political history and iconic styles. That doesn’t mean that because I find historic value in something that it can’t ever be replaced. The people of a city should plan its future, not the landmarkers alone, and if the latter constantly finds itself in conflict with the former, it calls into question what preservation is even about.

—

Cities are often faced with two polarizing extremes: freeze themselves into museums or develop at the sacrifice of the past. Tokyo is one of the most affordable metropolises on Earth but in terms of old or homogeneous and historic architecture, it’s notoriously lacking. The homes in Japan have a lifespan of 30 years, are frequently demolished and redeveloped, and lack any consistency in neighborhoods rich or poor. In contrast, the French preserve the core of Paris as a living museum for the rich and a lottery of long-timers under rent control, while rapidly developing its suburbs with high-density modern housing, connected with regional rail for most new families, refugees and immigrants.

Though it’s never said outright, older cities like San Francisco in the 1970s adopted the Parisian approach of treating all housing over the age of 40 as untouchable and unchangeable — whether it’s a Victorian, a dingbat, or a stucco box. The city mostly develops its former industrial lands for offices and service jobs, and depends on its suburbs to develop its farms and open space for future San Francisco workers. It’s a philosophy of stagnation that San Francisco pays for with virtually every neighborhood in the city having a median income in the rich or upper-middle income category, with only a few exceptions. Los Angeles is often worse, threatening the oldest oak trees on earth with sprawl to preserve the core of the city from changes.

The neighborhood shops, cafes, farmers markets, public services and economic engines that keep historic cities in statis are entirely sustained by workers and families for whom the preservation structure excludes from residency. Cities that outsource their working class needs to stagnate themselves in their core aren’t really cities, but museums and vacation towns for the rich and a few housing lottery winners. Much like Venice, which isn’t a real city anymore but a preserved, tourist playground.

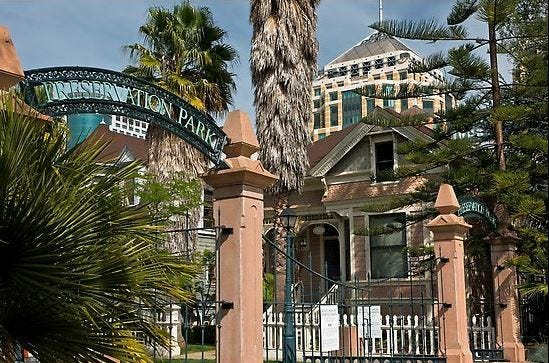

This binary of growth and preservation is fake. Great growing cities like Singapore for example I think do some of the best historical preservation. Chinatowns are good examples of preservation. Historic preservation is good because it’s not only a living history lesson for curious onlookers like myself, not only because you can experience different lifestyles lost to time, but you appreciate a city’s changes by having an earlier point to measure it. What’s the point in traveling to different cities if they’re all just solely modern metropolises in a globalized world?

One of my favorite local examples of preservation is Preservation Park in Oakland which collected an assortment of high quality and unique Victorians and placed them into a district. It’s a truly immersive feeling that conveys what life was like for rich people during the old times. I’ll also admit that some of the best history lessons are over landmarks that no longer exist. It’s enthralling to examine old pictures at a plaque and wonder what was. Sometimes its more enthralling than the history itself whose preservation can be underwhelming.

Pro-development individuals who, in indignation at bad preservation rules, declare all or most historic preservation pointless and opportunistic are dumb. I strongly oppose the idea that all or most historic preservation is worthless just because the system is misused by some people or that debates are contentious. They should be contentious!

I would reform landmarking so that a decennial Census would be conducted to determine the historical merit of every structure and area of a city. This would allow for a comprehensive look at history rather than a selective one. It would also bar landmarking in between these periods to discourage bad faith use of preservation to just circumvent general planning.

Okay, here’s a cool project I’ve been working on that I can use your help with!

When I was a kid, I used to sit on these huge pillars while waiting for my bus after going to the library. As an adult, I did some research and discovered that they are decayed relics of an East Bay streetcar station that used to have beautiful lanterns on them designed by the lead architect of the University of California campus. When automobiles replaced the streetcars, the lanterns were destroyed but the pillars remained in decayed form. This is one of the three sole remaining streetcar stations still surviving in the Oakland metro area, however, it has decayed and become a curiosity to the public.

I’ve been knocking on doors every weekend to restore colorful lanterns on this station for future bus riders and library patrons. My leading this campaign was a surprise to local preservationists whom I’ve butted heads with but also proof that I do care about history! I’ve raised 2/3rds of the funds so far and have only $5,000 left for the lantern maker! (Link here).

If any readers donate I will thank you by name and personal card at the grand reveal!