Berkeley Rents Fall Amid Construction Boom

The city's government rental registry reveals that rent controlled apartments are declining in price as Berkeley undergoes a housing boom.

If you’ve been to Downtown Berkeley or along San Pablo Avenue in the last couple years, there’s been a large development boom of apartment homes. A lot of newcomers to Berkeley don’t know that this is a very unusual sight for a city that in the last 50 years built virtually no new housing up until recently. Since the 1990s, there has been a debate over whether allowing developers to construct housing again would tame housing costs or worsen them. We finally have some answers.

Berkeley is among eight cities in California that has a “rental registry” where certain landlords must register their homes with city and report what their rents are with each new lease or change. This registry was made to monitor and make enforceable Berkeley’s early rent control ordinances passed in the 1970s. The registered units consist of any apartments built before 1980, i.e. rent controlled ones, and some single-family homes renting out bedrooms. (If you’ve ever been curious what the rents are in a rent controlled complex, you can search the registry and find out.)

While state law prohibits imposing rent control and therefore the registry on homes built after 1995, Berkeley had effectively banned new housing from the late 1970s till the 1990s. Most apartments in Berkeley long predate 1980. So the rental stock not in the registry is the more expensive, market-rate complexes downtown built in the 21st century. Rental data for any city is usually tracked by a sample of rental units of varying ages from real estate companies like Apartment.com. But Berkeley’s rental registry is far more powerful in that it’s a live snapshop of rents for almost our entire pre-1980 housing stock.

Among researchers, the evidence is near unanimous that building market housing reduces home prices. An emerging debate is whether development lowers rents for everyone or if it’s only lowering rents for similarly expensive rentals. The fact that the city’s rental registry almost exclusively consists of older apartment properties that overwhelmingly house the city’s low income renter population aides this quest.

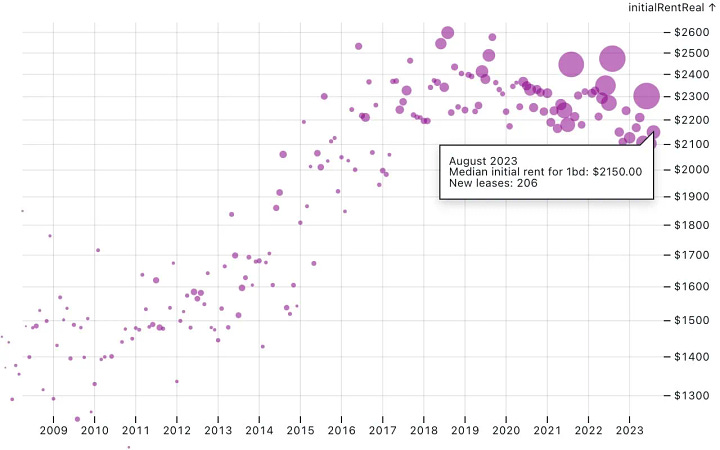

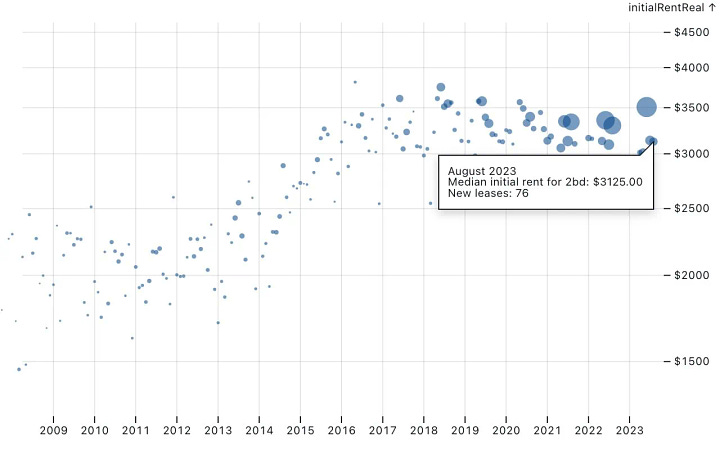

Data scientist Jeff Baker has analyzed and plotted the rental registry to give insight on Berkeley’s older rental housing stock. Note that when a rent controlled tenant vacates, the landlord has the power to reset rents to whatever they want, but increases are limited for the duration of tenancy. Those new lease rents are what’s reflected in the data below.

Since 2018, initial lease rents in older apartments have stopped rising relative to inflation. Since 2021, monthly-reported median real rents (inflation adjusted) in older 1-bedroom Berkeley apartments have been dropping 2.5% annually. Real rents for 1-bedrooms are below 2016 levels and in nominal dollars (absolute price not adjusted for inflation).

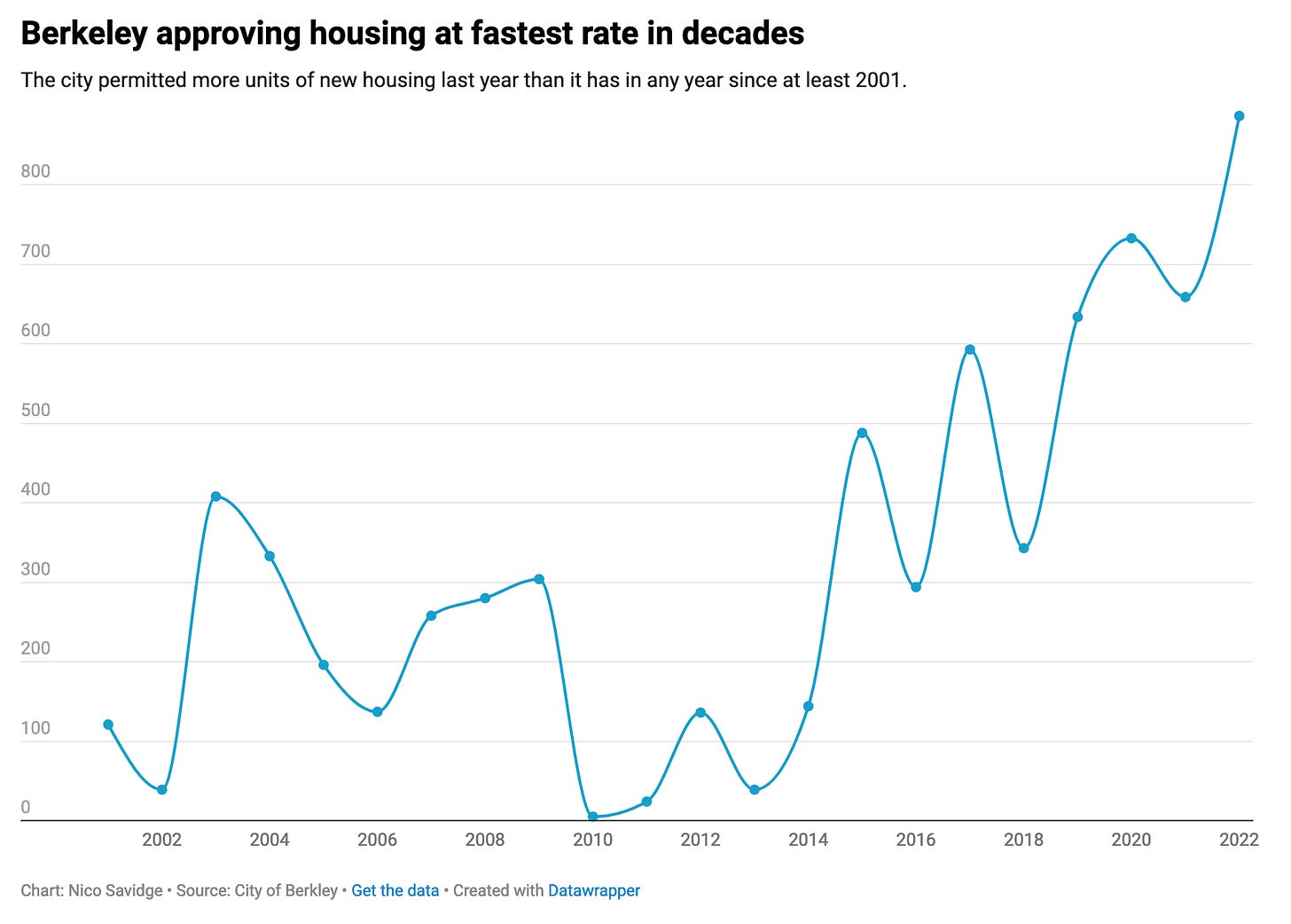

This is in stark contrast to the rest of the country where rents dropped in 2020 but rebounded back to growing in 2021. The declining rents coincides with the data from Berkeley’s Planning Department showing the city has been approving more housing than it has since the 1960s. Over 800 new homes were approved just last year alone. Berkeley has outpaced San Francisco by 50% per-capita last year in home approvals. The swell of new rentals downtown is pulling thousands of people away from the older housing stock. This increase in competition is forcing landlords to drop rents, who cannot continue to charge ever-higher prices for older rentals.

What happened in the mid-2010s that led to this filtering down of rents we see today?

After two decades of community debate, Berkeley voters overwhelmingly approved in 2010 and 2012 to re-zone downtown for a housing construction boom. But downtown housing projects were constantly held up in litigation by NIMBY groups and the city council. In 2017, the courts neutered a lot of methods to block new housing by ruling that Berkeley (and all California cities) had a legal obligation to follow its own zoning laws.

High profile losses for the NIMBYs by growing YIMBY residents and student uproar indicated a citywide attitude shift on housing. Since then, the city council has increasingly supported housing projects that would’ve been considered controversial years ago and the city’s anti-housing development legacy has declined significantly. The population of Berkeley now seems to be in agreement that if new housing should be allowed anywhere, it’s downtown and around campus.

Some will ponder if there aren’t other factors at play like a declining population. There is no de-population occurring in Berkeley like San Francisco. In the midst of the 2020 lockdown, Berkeley posted its highest population count ever at 124,000 residents. The latest 2023 statewide population estimates indicate that Berkeley is number 5 in California for population growth since 2022. Rent declines aren’t being caused by declining student enrollment either. The University of California has enrolled an additional 14,000 students to the Berkeley campus since 2019 and numbers have held steady all the way up until the latest headcount in 2022.

The clearest evidence that this is development-related is the homeowner market. Berkeley’s not building any new homes you can own, only rentals, and has strong rules against converting rentals into condos. Berkeley now has one of the worst homebuyers markets in the United States because there’s no new inventory for single-family homes and condos. Berkeley repeatedly ranks #1 in houses that sell over asking in the U.S. and consistently leads the Bay Area in the same metric. You cannot become a homeowner in Berkeley unless you’re a millionaire, which was not the case even a decade ago. The town is highly, highly desired to live in but we are not building ownable homes due to how we impose fees on condos and condo legal issues.

After so many years of debate, we now see the results of Berkeley’s building boom. It’s not only reducing rents in older apartment complexes, it’s probably keeping students closer to campus and out of quieter neighborhoods. If only we had done this decades ago instead of in 2018. The evidence was always clear that ending the monopoly landlords had on the market by swelling the city with lots of new housing would force rents to drop.

However, Berkeley continues to face many housing issues. Berkeley is not meeting our state-mandated low income housing quotas despite the city producing more subsidized housing than in recent memory. We are not producing owner housing so families are forced to move out if they’re not millionaires.

This doesn’t take away from the importance of declining rents in older properties, which prevents gentrification-induced displacement, homelessness and makes rents more affordable for housing seekers. Rent control has necessarily stopped extreme rent hikes, but building housing is sending rents downwards — they work best together. Moreover, Berkeley and the Bay Area must raise additional bond measures to finance low income, subsidized housing and re-examine barriers discouraging condo development over suburban sprawl. If we can get those production numbers up, existing prices will drop even faster and everywhere.

—

Props to Jeff Baker for plotting the rental registry’s rather clunky and hard to access data. Give him a follow if you like Bay Area data.

Update: Berkeleyside did an article on this holding off on making similar pronouncements until the latest preliminary report was confirmed. The latest report indeed shows rents continued to drop as of November 2023.