Berkeley’s Culture War : EE vs. FF

My long awaited rant on why you should vote Yes on Measure FF and no on Measure EE in Berkeley.

Point of clarification: Measure EE does not ban the expansion of bike boulevards but it doesn’t fund expanding more of them outside the existing seven.

Berkeley voters will decide between two competing ballot measures on street paving.

Measure FF — endorsed by almost all elected Berkeley representatives and two of the three mayoral candidates: Adena Ishii and Kate Harrison — raises a 17-cent per square foot parcel tax to meet the city’s repaving and sidewalk repair goals. The measure also funds safety improvements with re-pavings, such as painting new crosswalks, sidewalk repair, bus and bicycle lanes, pedestrian flashers, road diets, and school zone speed limits where deemed necessary traffic engineers and the community.

Measure EE — written and endorsed by an anti-bike lane coalition — raises a 13-cent tax for street paving and sidewalks, but prohibits any expansion of the city’s 7 bicycle boulevards, allocates little to pedestrian improvements on the remaining 544 car-only roadways, and gives no priorities to public transit. Whichever measure receives the most votes and reaches 50 percent “Yes votes” shall be the enacted one.

Both Measures FF and EE have oversight committees, except EE’s is independent and FF’s is appointed by councilmembers. The appeal of an independent committee for Measure EE is that the appointees would mostly be from a lottery of random citizen applicants, rather than people with engineering expertise and people from neighborhood electorates whose residents generally vote for street safety. The types of people who would bother to applying to an independent committee are going to be pro-driving people who are personally motivated to contradict initiatives to make alternatives to driving safer.

The origins of these competing measures began with the city’s poor paving and skyrocketting injuries and deaths on Berkeley streets. The City Council put up a massive bond measure (Measure L) in 2022 to fund street repairs and low income housing, but only a majority and not a super-majority voted for it so it failed. (Vote Yes on Prop 5 to lower the bond threshold for low income housing bonds from 66.7% to 55% so we don’t get silly measures like these). Measure L’s opposition was as diverse as its support: suburbanite progressives who don’t like urbanism and fiscal moderates who don’t like taxes.

An array of ideologies from all over the city, pro-Measure L, anti-Measure L, pro-car, pro-bike, pro-transit and everything else came together to work on a street paving measure as a truce which eventually led to Measure FF. Most of the pedestrian, bike and transit advocates made concessions to the car supporters — despite the fact that three-fourths of Berkeley residents do not drive their cars to work, making it and San Francisco the least car-dependent cities west of the Mississippi River.

Safety advocates surrendered bike lanes on Hopkins Street to appease the pro-car residents there and wrote into Measure FF that funds could not build a cycletrack there. Originally, FF would completely cover all identified expenditures for street paving and safety improvements with a 35 cent tax, but to appease the anti-tax constituency they cut Measure FF in half to 17 cents. Then they added a completely pointless and redundant oversight committee to FF, to appease the conspiracy theorists who charge that traffic engineering decisions are done by sinister planners.

For most part it was a fruitful endeavor, as Measure FF has an unusually diverse body of support. Prominent anti-Hopkins Street bike lane people like former councilmember Laurie Capitelli and Stephani Alan sit alongside the same pro-bike and transit activists they had fought against on the Measure FF steering committee. 8 out of the 9 Berkeley city councilmembers endorsed Measure FF, including councilmember Susan Wengraf of the Berkeley Hills who represents the highest concentration of car ownership and driving residents in Berkeley. The entire Berkeley School Board endorsed FF because the biggest threat to school children is being hit by drivers en-route to school. The Firefighters Union, whose priorities are decreasing response times to medical and fire emergencies, backed Measure FF because they defer to research that street parking and car congestion is the primary cause of longer response time and disaster evacuation.

The anti-Hopkins bike-lane people consisted of two contingents: normal people who had criticisms of the project, and they’re on board with Measure FF. The pro-car ideological zealots that engaged in conspiracy theories about "Agenda 21" and “paid bike lobbies” simply pretended to be interested in a truce just to wear down Measure FF. The most fervently pro-driving contingent of the Hopkins Bike-Lane War had no intention of ever allowing a single dollar to go to any other transportation in Berkeley except cars. The Measure EE people known as “Berkeleyans For Better Planning” revealed their red-line during negotiations: there shall not be any road re-designs and safety engineering with any re-pavings, and no funds from this measure will go to expanding the city’s Bike Boulevards beyond the woefully inadequate and geographically limited 7 out of 551 roads.

Knowing this would be rejected, they broke away only after many concessions were made, and challenged FF with a competitor “Measure EE”. But since the 1950s are over and being blatantly pro-car doesn’t sell well in a highly-educated and cosmopolitan town, nor with its new generation of young families who don’t like driving, they wrote a ballot measure to resemble FF. To obfuscate EE’s lower tax ploy with an empirical basis, the 13 cent tax is based off the “deferred maintenance” (i.e. delayed street improvements) cost estimates from the City of Berkeley. FF’s was based off both deferred and projected maintenance costs because it makes no sense to pave streets that are behind schedule and not also street pavings that are due.

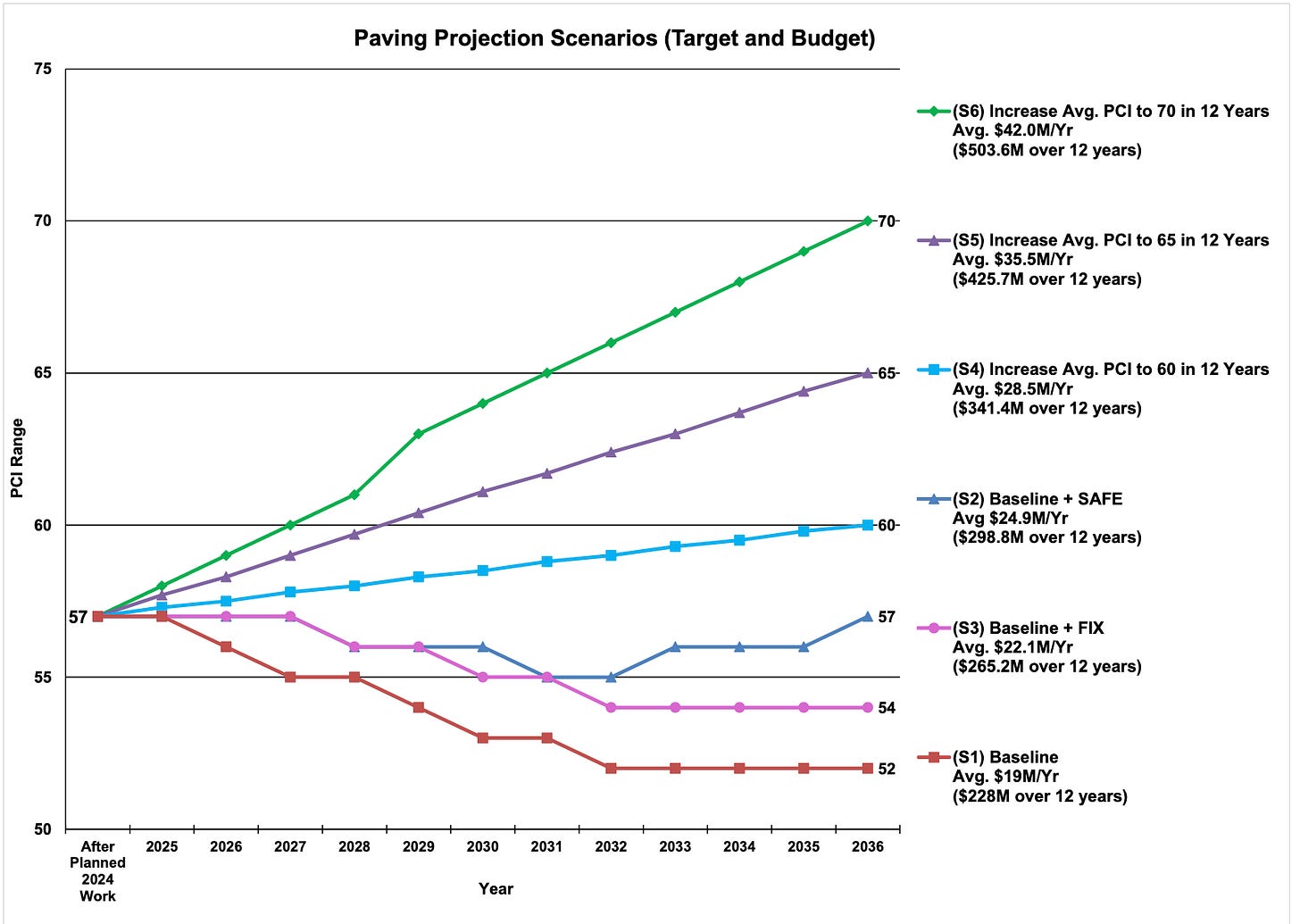

Both measures however were dunked on by the bombshell city report that neither FF or EE would raise enough money to reach the city target rating of 70 out of 100 for roadway pavement conditions, due to the dramatic inflation of construction costs. However, the non-partisan report also found that Measure FF’s budget would maintain the city’s pavement quality score from 57 in the next decade, while Measure EE would decrease our score from 57 to 54. (It’s the image at the top).

So why would driving enthusiasts put up a measure that worsens roadway conditions for drivers? Because the point of Measure EE is not to fix Berkeley’s paving problems, and they probably don’t think their measure will pass anyways. It is a culture war measure whose sole intent is to peel away enough voters who do not understand any of this stuff, who will opt for the smaller tax and buzzwords like “independent committee” and punish the city’s climate action plan of making alternatives to driving safer. If you look at their few endorsements, its a Who’s Who of “I Don’t Like Change In Berkeley” veterans that have been fighting against Berkeley changing since forever.

The old culture war of “I want Berkeley to be like the 1950s and suburban” vs. “I want Berkeley to grow and not be car-centric” plays out on lawns throughout North Berkeley. The people with “No Towers at BART” signs swapped them for “Save Hopkins” signs and now Measure EE. The people with “Housing Not Parking Lots” signs swapped them for “Bike Lanes on Hopkins” signs and now Measure FF. Throughout the years I’ve witnessed neighbors in District 5 curse each other out or argue vigorously. One North Berkeley woman even berated my girlfriend to the point of making her cry with fanatical conspiracy theories about us being secret outsiders trying to force everyone on bikes.

Even though tensions are high in North Berkeley, in the long-run Berkeley shall move away from the car-centrism of the 1950s no matter what. There’s an clear generational pendulum swinging from suburbanism to urbanism; parallel battles are happening in San Francisco with it’s Proposition K to turn a useless highway into a park. Every day, I walk through the Northbrae neighborhood and can see that when a new family replaces an older empty nest family, a lawn’s signs flip from anti-housing to pro-housing, and from pro-car to pro-transit and bikes. It’s just a matter of time, but unfortunately, neither our climate action plan or the death and injuries on our streets can simply wait this out.

The media has framed these Hopkins and the city’s culture wars broadly as between drivers and cyclists, but that’s actually not true. Many car-owners are supporting Measure FF. Councilmember Susan Wengraf, who represents the most senior citizen heavy, the most car-centric part of Berkeley, and has always been primarily concerned about fire safety is retiring and has no political incentive to support FF. She’s doing it because she sees the cars careening down Marin Avenue regularly, the people being killed in crosswalks, and the parked cars congesting evacuation corridors as not being sustainable.

Conversely, Measure EE’s chief architects and many prominent opponents of the Hopkins bike lanes are themselves cyclists. This has baffled me and many others for quite some time. Why would people advocate against their own safety? I didn’t understand it until councilmember Sophie Hahn, who has remained neutral on EE and FF because a high concentration of EE people and pro-FF people like me who live in her district, told me casually one day: it took a long time to force people into cars and it’ll take a long time to get them out. That’s when I understood that it’s a generational ideology that supersedes personal interests and why the dueling lawn signs have such a clear age correlation.

Most Americans who grew up between World War 2 and the 1980s have been taught and trained that the only way to move is by automobile. Berkeley was originally built as a relatively dense streetcar suburb for trains, bikes, pedestrians, automobiles and horses. But by the 1970s, the fossil fuel and car industry indoctrination succeeded at demolishing our trolleys and giving their right-of-ways to cars, blocking our buses with endless traffic, killing walkable businesses for car-oriented supermarkets and gas stations, widened roadways and conquering curbs for street parking.

The bike riders who grew up in the middle 20th century and back Measure EE see their bikes as more of an enthralling sport or recreational exercise rather than a legitimate means of transportation. In conversation with one neighbor regarding the EE provision that no funds to go expanding bike boulevards, I asked if she felt comfortable enough to let a child or senior bike down Gilman Street by themselves. “Of course not,” she replied, but she thought that it was impossible to ever make a city safe enough for cycling and that not everyone, especially seniors, could be fit enough to ride a bike.

Of course, in many countries outside the United States, it’s more common for children and seniors to ride bikes safely on the majority of their roads than it is to expect them to get a license and operate a car. Even the identity of “cyclist” reveals how the status-quo is “motorist” in the United States. Outside the country, nobody but bicycle enthusiasts would identify themselves by a common means of transport like a bicycle. If you ever want a laugh or cry, accompany foreign UC Berkeley students on their tours of the city, and it’s hilarious watching them react to our car-centrism. All of them come away saying the same thing: they don’t want anything like our streets back home. One Chinese friend of mine from UC Berkeley explained it succinctly: “In Asia, cars are a luxury for the rich; in America they’re a necessity for the poor.”

Putting aside the pro-cars zealots, the average anti-bike lane people, especially my elderly neighbors in Northbrae who support EE, genuinely fear total isolation if their cars are taken away. (Nobody’s actually taking cars away, but when cars dominate every inch of space, any reduction can feel like oppression.) They can’t imagine themselves feeling comfortable enough to ride a bike even though its far more common and economical in the rest of the world for seniors to use bikes than cars. The bus doesn’t come that often and they can’t walk with a handful of groceries. For them, making it harder to drive inherently means taking away their mobility and their livelihood — isolating them from friends and family.

That’s the irony of the whole culture war: the people whose age warrants alternatives to driving the most are usually the ones isolating themselves with mandated car-centrism. The anti-bike lane people always say in their blogs with dripping grievance and condescension how the bike advocates are young and fit and they are old and not. They complain they can’t take the bus because it doesn’t run enough — that was a common line on Hopkins Street. Yet, many of EE’s same supporters are the same people who 14 years ago successfully killed bus-only lanes in Berkeley, in defense of parking.

For people new to Berkeley, the Battle of Bike Lanes today was the Battle of Bus Lanes a decade ago. And they won that one: Berkeley has no bus priority lanes so buses get delayed and snarled downtown. It’s the same people who spent the last 10 years fighting bus-only lanes on San Pablo Avenue and killed San Pablo Avenue bike lanes. It’ll be the same people fighting against a bus lane on University Avenue in the future. The consequences of these actions have been reduced AC Transit ridership because buses are delayed by car traffic, resulting in service cuts to senior-heavy areas, and cutting off Berkeley’s direct bus service to Kaiser Hospital.

Imagine if the time and effort put into Measure EE instead went to fighting AC Transit cuts that will strand seniors in the Berkeley Hills and cuts on Paratransit for people with disabilities. Not one of those folks showed up to stop public transit cuts, but the Measure FF supporters did. The car people oppose any change to make it easier and safer to traverse Berkeley by bus, bike and on foot, then cite that impossibility as to why everyone must drive. The energy behind Measure EE really is motivated by irrational grievance at the perceived superiority of non-drivers, but in their bid to try and harm us, the only people they’re really harming are seniors they purport to defend.

My elderly neighbors complain constantly about hitting these little bumpers in the intersection at The Alameda and Hopkins Street, designed to stop drivers from hitting school kids and cyclists near the curb. I have also driven through this intersection and it’s the easiest thing to world to avoid hitting by simply doing a proper turn and using your eyes. Anyone who cannot see these bumpers is a bad driver or is too impaired to drive. But my neighbors don’t want to admit they’re approaching the age where they can’t see things on the road so they just blame the traffic improvement instead. And when they lose their license, they’ll be isolated at home because there won’t be safe alternatives to get around.

I’m not a cyclist. I take transit and walk but I use a car to get between North and West Berkeley. I used to cycle in high school but after getting hit off my bike by a driver on MLK, I refuse to ride again until there are safe East-West bike street that don’t require extensive detours. If there was a fully protected bike lane on Hopkins Street or Rose Street, I would dump my car tomorrow. But there isn’t, so I will continue to drive, which means I will contribute to traffic congestion. I will park on the streets directly in front of businesses and force people with chronic pain to walk further. I live right by the Northbrae fire station and I will slow down fire and ambulance response time on MLK Jr Way. I don’t have a choice; the pro-car people are forcing me to drive.

Every person not in a car is more parking and less congestion for workers and seniors who truly need to drive. Of course, not everyone can ride a bike or take a bus. That’s why re-engineering more than 7 of our 551 roads to accommodate people who shouldn’t have to drive is necessary. We can give space to the motorists who truly need their cars, which is significantly lower than that actual people who drive. Since the protected bike lanes have gone up on Milvia Street south of University Avenue, car traffic has plummeted and the street is full of cyclists. It’s so safe you can walk in the street now and people do regularly.

Despite this, I have criticisms of Berkeley’s safety improvements. I think Milvia by University Ave. was a missed opportunity to fully bar vehicles from traversing more than one block. All too often, the traffic engineer compromises with pro-parking merchants and the result is no one is satisfied. I would like to see more European approaches to bicycle safety that are not overly complex such as roads like these.

Measure EE states that the seven existing bike boulevards are good enough for cyclists and that we don’t need more, but right now, pro-EE commentators are on Berkeley NextDoor are making posts complaining about bike boulevard getting safety improvements. And every other post by them advertising for their measure is complaining about the Milvia bike lanes impeding their ability to drive. I’m doubtful they’re satisfied with even the 1.2% of streets being accessible to bikes.

I live close to Rose Street and already see the consequences of Measure EE going citywide. The street was recently paved with zero safety improvements and now Rose is less safe than its ever been. Cars that used to go 25 MPH with pot holes have now sped up to 40 MPH, often right in front of middle and elementary schools. Lack of safety improvements resulted in a teenage girl getting knocked off her scooter by a speeding motorist at MLK Jr Way a year ago. Councilmember Sophie Hahn said that before everyone wanted the street paved, and now everyone wants the cars to slow down. It’s the folly of not doing safety improvements with re-pavings: drivers get comfortable, speed more, and it is only a matter time until someone gets killed when we could’ve done it right the first time.

I wish Measure FF was going to transform Berkeley into Amsterdam, Tokyo or Paris but it simply repaves the streets to get closer to the city’s street paving goals. Even if you don’t like supporting other modes of transportation besides cars, objectively, more streets will be paved under FF than EE and most neighborhood streets will simply be paved without any changes.

But when Alcatraz gets paved, perhaps pedestrian signals will be added to make drivers stop so residents don’t have to gamble for their lives when walking. When Gilman gets paved, bulb outs and mirrors can be built so drivers pulling onto Gilman can clearly see cars coming. It may mean relief for the tens of thousands of bus riders delayed every day by a handful of delivery drivers blocking bus stops on Durant. FF ensures that roads in the Berkeley Hills are paved and sidewalks can finally be added where there weren’t any before. It means innovative road engineering to facilitate slow driving by schools like Allston Way in front of Berkeley High.

And for most motorists who have to drive, it means streets safe enough that you don’t have to live with the trauma of killing someone with your car. People being killed by drivers is an increasingly common crisis that can be committed by drivers of any age when your street engineering is as unsafe as Berkeley’s.

Vote for Measure FF as soon as you get your ballot, and equally important: vote No on EE.

So many falsehoods here (in addition to the one you just corrected). For starters, re "[EE] prohibits any expansion of the city’s 7 bicycle boulevards, allocates little to pedestrian improvements" -- absolutely false. Show me where there is any prohibition on cycle tracks in EE. What EE does is require that we study the new cycle tracks that have gone in before we build more -- there has been none of that, so unfortunately we have no baselines to measure usage or safety. This suggests that these tracks are something of an ideological project. Cycle track backers seem very afraid of studying these things.

Re "three-fourths of Berkeley residents do not drive their cars to work" -- maybe, but less than four percent commute by bike, according to the U.S. Census American Community Survey. Yet, FF would spend up to $100 million on cycle tracks and NOT fix all of our sidewalks, which pose tripping hazards to everyone and create barriers for the disabled. Here are the figures on the sidewalk allocations of both measures from the same city report that you referenced:

FF = $ 1,971,981 per year (See table 3)

EE = $ 2,933,291 per year (See table 6)

EE is for everyone, especially pedestrians. FF is for the relatively few cyclists.

More at FixBerkeleyStreets.com. Full disclosure: I am on the steering committee.

Love that old dude's dapper outfit in the bottom right.

I feel like there needs to be some ways to make walking and biking "cool" and driving "uncool" to the mass public. I don't know what those ways are, though. It's very healthy to walk and bike, maybe there's something there.