Berkeley's District 4 Election

My take on the District 4 election that's ongoing and thoughts about the district as a whole.

Disclaimer:

I agreed not to make political endorsements due to my data science job. While I can still do political advocacy and have opinions, I must make clear that none of my views represent Terner Labs or Terner Center at UC Berkeley. Moreover, I do not grant permission by any campaign to use any of my statements as endorsements for a candidate.

If I were to vote in District 4, the Daily Californian's endorsements and the Sierra Club's linked here would be on my ballot. These are not endorsements.

—

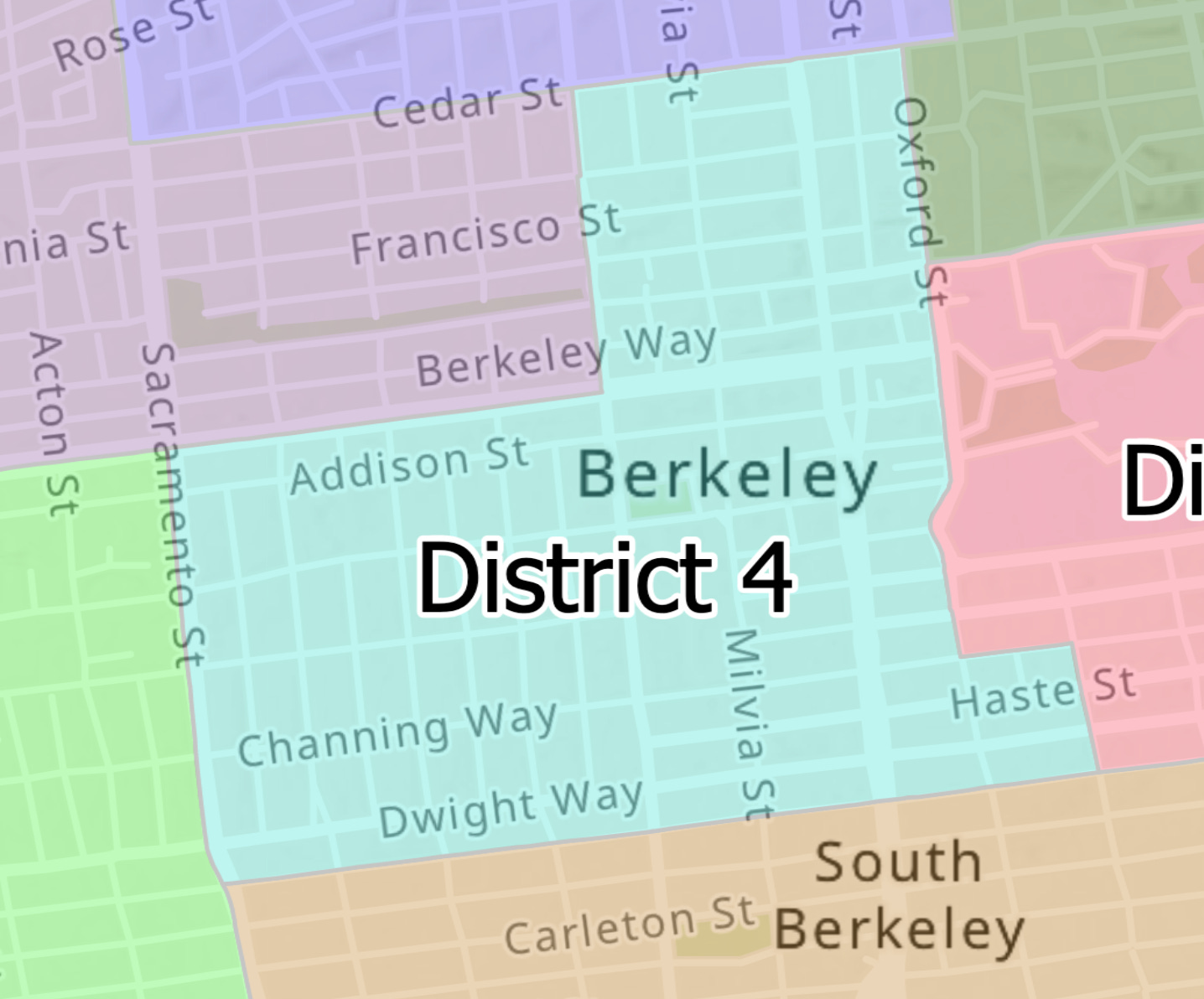

Councilmember Kate Harrison who represented downtown and central Berkeley resigned from the city council several months ago. A replacement election is to be held on May 28th. You have received a ballot in the mail if you're registered and if you haven’t, you need to go to your polling place and register ASAP.

District 4 is small but contrasts between the low-density Central Berkeley and the high-density Downtown. The Central Berkeley neighborhood is split between two prominent and opposing generations: new, younger, urbanist white and Asian families of upper-middle class wealth; and older, Prop. 13 benefiting, white homeowners who moved in after the counterculture days. The once prominent Black community in Central Berkeley has been on a 50-year decline and barely exists anymore. Central Berkeley is my childhood home and my family lived there for four generations, but I left that district and my family left Berkeley in 2016.

In 1970, Central Berkeley, my home, was different. It was an integrated and diverse district: 20% Black, 60% White, and 20% non-white, with an overall population of 4,700. Back then, Berkeley added almost double the housing we build today, but the homes were ugly dingbat apartments, which were blamed for deteriorating Central Berkeley with population growth and the demolition of historic houses.

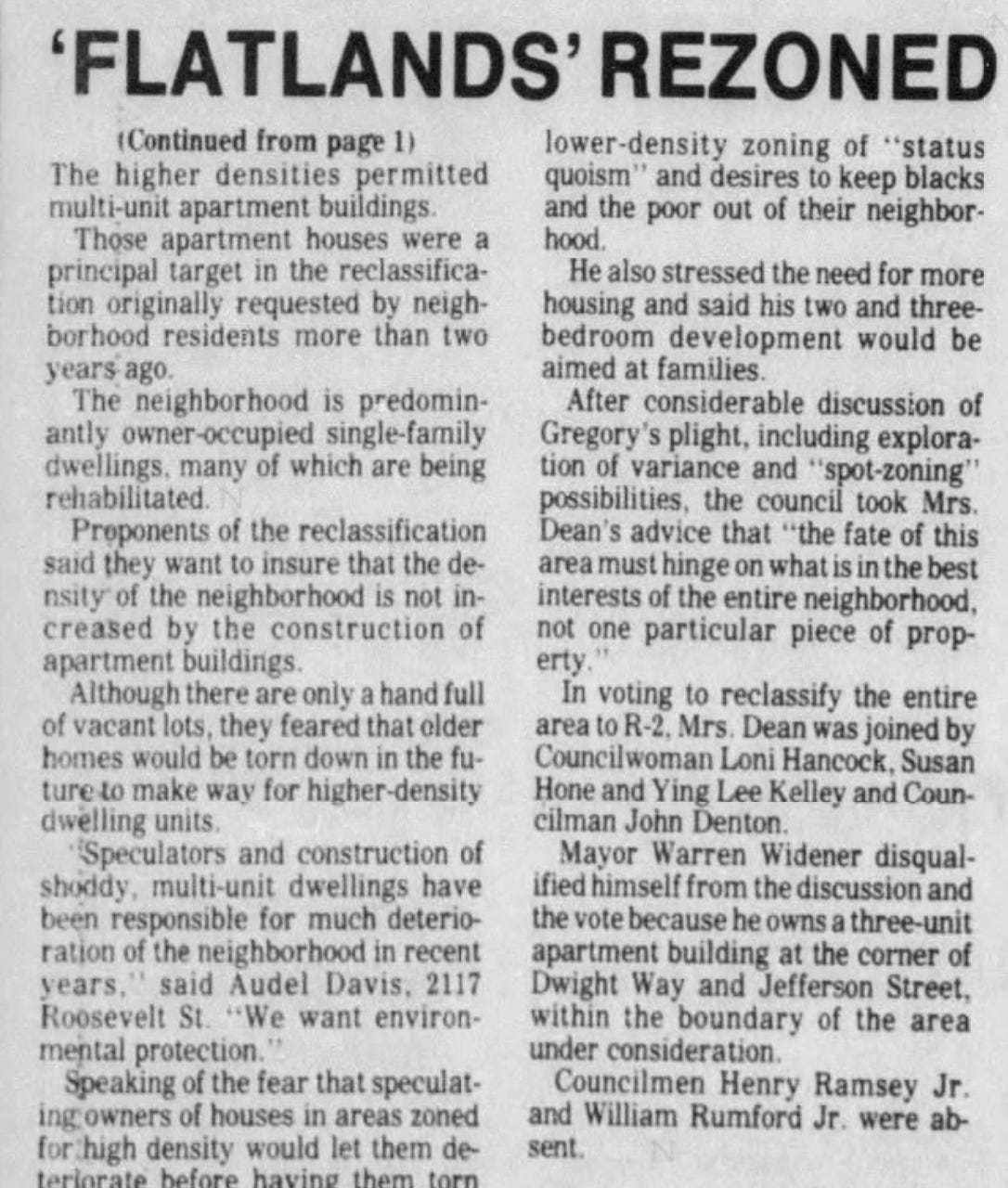

In 1975, pro-preservation neighbors and the city council joined hands to reverse this urban decline by down-zoning and banning high-density apartments in Central Berkeley. One dissident property owner predicted the outcomes and motivations of banning apartments to the City Council: “He accused supporters of lower-density zoning of "status quoism" and desires to keep blacks and the poor out. . . ”

I doubt they were racist but there was certainly demographic change after housing construction ceased in Central Berkeley post-downzoning. The old houses that were being bulldozed for dingbat apartments were saved. Those houses were bought by the first wave of white families who aged out of the counterculture by the late 1970s. This followed subsequent generations of ever-wealthier families who bought the old houses of Central Berkeley, replacing Black homeowners or Black tenants in subdivided rental housing converted back single-family owner-occupied.

This valiant history of preservation is immortalized on plaques throughout the district. Despite California growing by 20 million people since 1970, this district has remained capped at 4,700 people, with little physical change since 1970, except one. The Black population in Central Berkeley dropped 26% in the 5 years after the downzoning. While the white population is identical to its size as it was in 1970, Central Berkeley's Black population has been in free-fall, from 1,000 Black residents to just 285, or a 70% decline.

This is how gentrification has manifested in Berkeley: the residents inside the same old homes replaced with wealthier inhabitants. The city and neighborhood's population is limited by zoning, despite intense bidding wars for homes and crowded open houses for rental apartments. It’s falsely implied in media and discourse that Berkeley’s overpopulated and crowded, but Berkeley’s population never eclipsed its 1950 size of 110,000 people for 50 years. It wasn’t until 2020 where it reached 124,000 — growing only after the downtown plan of 2009.

The downtown plan was the product of former Mayor Loni Hancock. After seeing the severe homelessness crisis and gentrification in the '70s and '80s despite rent control, Hancock and the once prominent leftist party proclaimed the down-zonings went too far. Hancock launched the downtown plan in 1990, and once again allowed privately-financed multi-family housing to be built in Berkeley, but only in downtown which had been dead and struggling. After two decades of intense battle between the anti-development and the pro-development sides, voters overwhelmingly permitted high-density housing to return to Berkeley in 2010, but in downtown and along Shattuck.

Downtown Berkeley is one of the only districts in the city whose Black population has grown and whose income and racial diversity increased. Downtown is now majority-minority, and in the last 10 years, the Asian, Black and Latino populations have all individually grown faster than the white population per-capita. Downtown's primary census tracts added 3,000 residents since 2000: 554 of them white, 423 Black, 1,298 Asian, 400 Latino and 188 Mixed-Race.

Downtown has a median income half of Central Berkeley. About half of downtown's population are college students, although that's one-fourth for Black residents. The subsidized housing is inhabited by low-income families since students don't qualify for "affordable housing" as dependents. The students move into the market-rate apartments, which ease up the student housing shortage since UC Berkeley dorms are at 99% occupancy. It has successfully kept students away from the rent-controlled older apartments in the rest of Berkeley.

Fiscally, housing development has been positive for Berkeley. Thanks to Prop 13, one apartment complex downtown pays as much property tax as 1,000 single-family homes, almost single-handedly keeping Berkeley in fiscal solvency rather than dooming us to bankruptcy like other suburbs. The climate benefits have also been tremendous. Downtown Berkeley, along with Southside Campus, has the lowest household emissions of any neighborhood in the city.

What’s frustrating is that this has been largely absent from the political discourse in the District 4 race.

When I went to the District 4 community forum or read responses to Berkeleyside's questions, it felt like Bizarro World. According to several candidates and numerous questions by chamber of commerce groups and moderators: downtown is allegedly run down, full of vacant housing and business, the new housing is causing gentrification, there’s criminals running around, homeless has gotten worse, and downtown's in desperate need of "revitalization."

I have no idea what revitalization is needed. The high-density apartments in Berkeley have a 2% vacancy rate according to the rent board's registry, they're filled to the brim. Other than a single block that went through a nearly 10-year development battle, every other block has people crowding its sidewalks with commercial activity. The homeless count in Berkeley in 2022 was 1,057 people and in 1994 — 28 years ago — the count was basically the same: 1,034. It’s lower per capita because there are now 22,000 more people here than in 1990, and the latest 2024 count says it dropped to 800. Homelessness is still a major problem, it’s certainly gotten worse in the East Bay overall and post-Recession, homelessness is very deadly, but in Berkeley it’s not worse than it was 30 years ago.

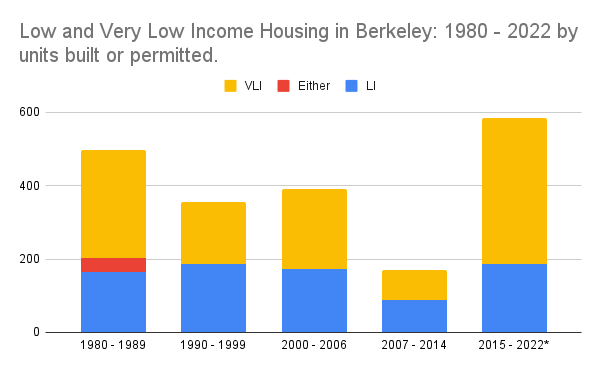

It’s repeatedly noted in city discourse that Berkeley has met its market-rate housing goals but failed to reach its low-income ones for the last RHNA cycle. This is valid but the only solution to that problem is more bond measures locally and more regional financing for subsidized housing. The last bond, Measure O, funded 11 major subsidized, low-income housing and shelter complexes. Yes, we didn’t reach our goals, but the city council in the last 8 years has permitted more low-income housing than any council in any previous RHNA cycle or decade since World War II. All possible due to Measure O and would've been continued with Measure L but it only got a majority, not an anti-democratic super-majority.

I got so frustrated at one District 4 meeting I just walked out. Zero questions about what single-family neighborhoods in the rest of D-4 needed to change. A complete fantasy world about downtown. No downtown residents were present asking questions, and the conversation about their future was dictated by homeowners in the low density areas. So eventually I asked what candidates would do to reverse gentrification in the rest of Central Berkeley (1:46:00) : Ruben Hernandez called for middle income housing, Igor called for more subsidized housing production via the landlord tax, Elena Auerbach called for examining white privilege, and Soli Alpert called for higher inclusionary zoning.

Downtown isn't perfect and could be a lot better by getting rid of cars on Shattuck. I like candidate Soli Alpert's idea of pedestrianizing Center Street and re-emerging creek so pedestrians can walk around like a park. The city should work with a nonprofit to open a cinema. We need more public seating. While improvements have been made on housing, we're nowhere near filling a 40-year shortage. Our failure to get Measure L — a lost affordable housing bond — to a (anti-democratic) super-majority of votes will jeopardize our low income housing pipeline.

The staffing crisis we have in our public departments after the Hopkins bike lane debacle is grinding our city functions to a halt and we need to rebound and build a better work culture in city hall. People don't want to work for the city of Berkeley because they think the town's run by lunatics, bullies, and council members who will throw staff under the rug after doing what they’re told.

Voters will choose between four candidates on May 28th to improve the city. Here’s my breakdown and evaluation of the four.

Soli Alpert: A tenant union activist who is on the rent board. He started in Kate Harrison’s office and moved to Rigel Robinson’s in recent years, pushing regulatory policies on real estate. He’s pushed for more socialist intervention in the housing market, such as Tenant Opportunity to Purchase, or “TOPA” which gives tenants a chance to organize with the city to buy buildings. He's passed a policy to expand eviction protections to duplexes and a vacancy tax to force old rent controlled apartments to lease out their units, again. He’s endorsed by councilmember Kate Harrison and various labor unions. His main concern is not land use or zoning, but he's supportive of high-density development downtown, putting him in the pro-development progressive camp.

Soli’s pretty thoughtful. We don’t always agree but he’s willing to have substantive discussions. I've argued with Soli about how to impose rent control or how set inclusionary rates on new housing for hours on the phone. He's made enemies in city hall with his battles with the departing city manager. He's had the longest, most anti-police record of any candidate and police unions are sending flyers against him. His voters will mainly be SEIU members, Kate Harrison supporters, and UC students downtown.

Igor Tregub: Igor is the most experienced of all the candidates in public service for the city of Berkeley. He's an energy scientist from the UC and a solar-power lobbyist — a rare case of that intelligence from the UC actually running for local office. He's quite center-left, but Igor's brand is all about making compromises between dueling sides. He is supported by a lot of community members in District 4, the Sierra Club and pro-housing groups.

Igor and I have butted heads often about the swiftness needed for housing reform. Igor supports whatever the community tends to support and wants to maximize community outreach, even if it takes a long time. He loves hosting meetings and hearings and going through the process. He’s the candidate of big compromise, and while I don’t always agree with that, perhaps during this period of intense polarization, that will be his appeal.

Ruben Hernandez: Ruben is the most focused on pro-housing construction and zoning reform of all the candidates. An aide of Councilmember Terry Taplin, he’s the most focused on improving the business district and making it easier for homeowners to build homes like ADUs. He’s received the majority of endorsement from the Sierra Club, pro-housing groups, the bike groups, the city's political and Democratic clubs, and construction labor unions.

Ruben is the most staunch in building more housing than any of the candidates. In the neighborhood I get the impression a lot of young families and bike community support Ruben.

Elana Auerbach: Elena regularly attends city council meetings and is a priestess of some kind of interesting spiritual church. She used to work on Wall Street and then got out of a supposedly famous cult. Now she's a Ceasefire protester who protests city council meetings and is a Berkeley Tenants Union member, but also a homeowner. (For reference: Soli and Elana will vote for a Ceasefire resolution immediately. I don’t know what Igor’s position is. Ruben is personally critical of Israel’s war but as a city wants a long community discussion before any resolution.)

She was recruited by the anti-development progressives that feel abandoned by Soli Alpert and Kate Harrison’s pro- or not-anti-housing development stances and their support for bike lanes. She’s staunchly opposed to the downtown housing plan and supports single-family zoning. She cheered for the court striking down SB 9 — allowing duplexes over single-family homes in the Berkeley Hills — at the community forum I attended when the news broke.

I’m trying to steelman her positions but the only things we would agree on is that council should pass a Ceasefire resolution immediately and the city should have a sanctioned homeless encampment. Especially as a transition zone into supportive housing. Her supporters on Facebook say that she's very principled. She’s the opposite of a mediator who bends to sentiment like Igor, but stands for what she believes in. She seems like a nice person, but I don't find being principled to be impressive if you're not open to being corrected.

Every time she talks about the city's housing issues she makes many unsupported claims and makes no corrections. The first time I saw her she said market-rate development caused Berkeley High's homeless count to increase; it had dropped to a decade low. Then the next time I saw her at a forum, she said it was proven that market-rate housing caused gentrification based on a study. That study was a paper from an organization whose correlation models just said it was "inconclusive." She said multiple times that downtown housing is mostly vacant despite rent board data showing its about 2% vacant.. (I believe they believe that homes for students that are vacant during summer break or winter break in the Census are vacant forever). Recently, she posted a video at a house party implying that everyone should have income high enough to afford a $1.5 million home. Her slogan is "for truly affordable housing", which I think means very low income but she didn't support Measure L.

The flyers she posts on every inch of public space say she supports bike improvements but it doesn't say the "Safe Streets" measure — which is the one supported by the bike groups. My friend who lives in D4 told me that Elana explicitly told her she was not supporting Kate Harrison for Mayor, because of Harrison’s support for the Safe Streets measure. But then later on at another forum she called for a car-free Berkeley, allegedly. Unlike her strong commitment to opposing Israel’s war and opposing housing developers, I can’t evaluate a lot of her other ideas about city government. They contradict each other, are highly idealistic, switches regularly, and all seem to have no specifics.

Though Elana has few endorsements by politicians or city political groups, she is resonating among the older, progressive Berkeley residents who dislike the city’s changes, like the mother of this New York Times author. There’s a lot of District 4 longtime homeowners who admired the 1970s downzonings and have seen the city’s housing attitudes change dramatically in ten years. From pro-suburban to pro-urban; from driving everywhere to reducing driving and encouraging cycling and transit; from pro-small homes and apartment bans to the erection of mid-rises. As the council embarks on its historic push to end single-family zoning, Elana’s platform feels like a clear call to cancel this and go back to the 1970s. Back to the old days when progressive included stopping growth.

This is a ranked choice election, and it is likely to be a low-turnout election. So, you should not only make an effort to vote, but also rank every candidate you’re content with being on your ballot. Voting exclusively for the one you like the most will result in your vote expiring if they’re not in the top two.

Wow - Berkeley politics is pretty mind-blowing.

Any thoughts on this dynamic:

"Very few downtown residents asking questions and conversations were dictated by homeowners"

Unlike some of the other things in the article, it's certainly not unique to Berkeley. But it continually means that homeowners will punch above their weight relative to renters. Which sucks. But it's not all that hard to attend a city council meeting, or at least organize your friends and family to get one person to attend and speak up.