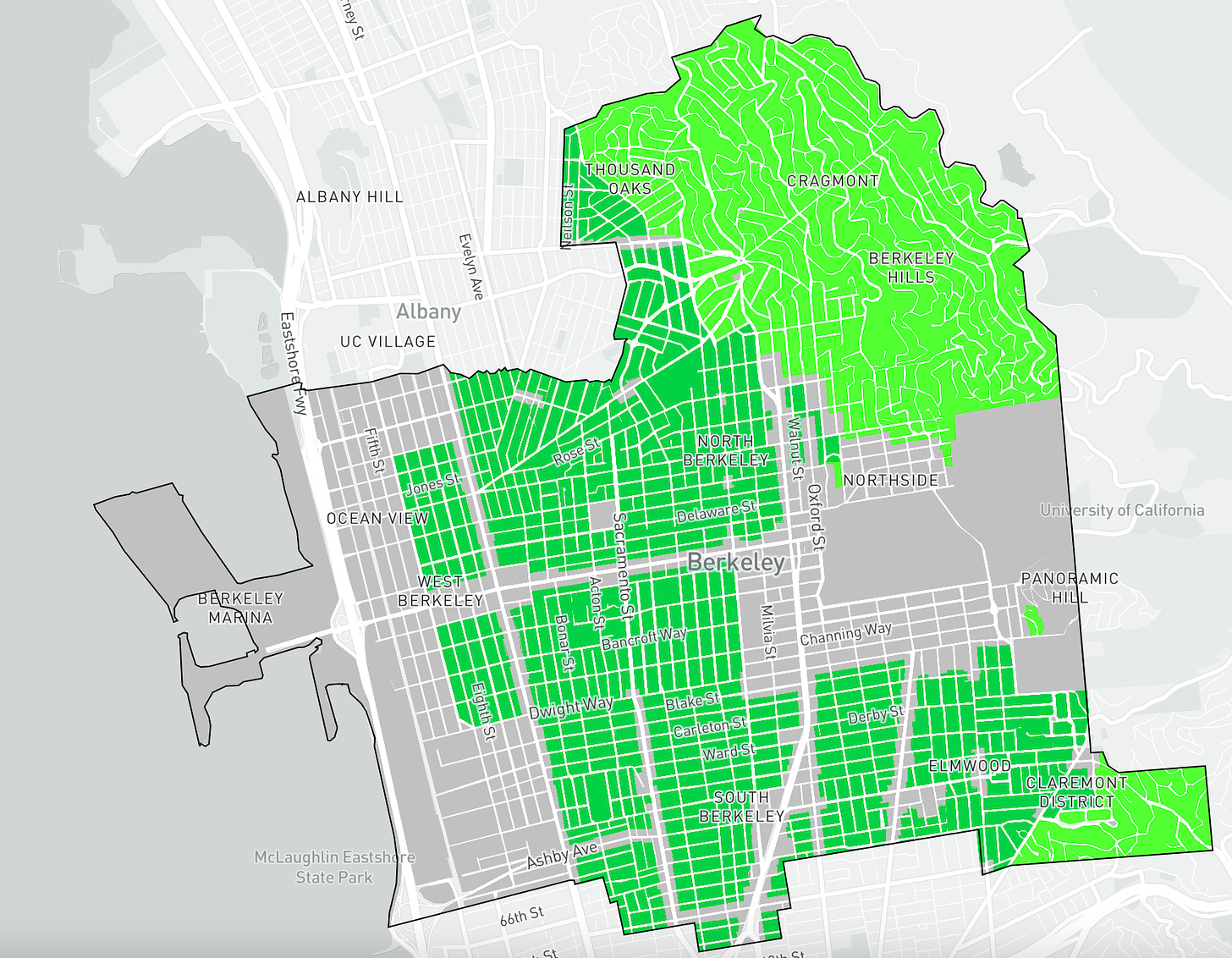

Berkeley's Upzoning Would Be Among Nation's Largest

A proposal to end exclusionary zoning would allow for 100,000 more homes in Berkeley's neighborhoods.

The city of Berkeley is on the verge of passing one of the largest zoning reforms in the U.S., per capita. If passed, the city’s zoning map would allow for over 100,000 additional homes in a city of 47,000 existing homes. As far as I’m aware, hardly any cities that have eliminated single-family zoning have allowed this many homes relative to their size.

Berkeley is known by academics for being the birthplace of “single-family zoning” a.k.a. exclusionary zoning. Invented by Berkeley's founding developers, exclusionary zoning prohibited the construction of apartments and multi-family homes in Berkeley’s elite neighborhoods to keep out non-rich inhabitants. This zoning code was quickly exported around the nation. Berkeley had a reckoning about this history in 2020 when race relations and the severe housing crisis in the city intersected. Following the lead of Minneapolis, Berkeley city council broke national headlines by unanimously pledging to end its multi-family housing ban, which composes one-half of the city’s residential zoning.

Nicknamed “Missing Middle” housing, the goal of cities like Berkeley was to allow for middle density housing such as small apartments and condos, in contrast to the single-family homes which dominate most neighborhoods and the high-rise apartments on congested corridors. As the city initiated the process of zoning upheaval, several problems became immediately apparent.

Here are the four zoning codes which currently represent most Berkeley neighborhoods:

R-1: One home per lot or estate, only. Bans apartments in 49% of the city.

R-1A: One home per lot or estate, unless the parcel exceeds 2,400 SF which allows for an additional home.

R-2: Two homes on one parcel, only.

R-2A: One home per every 1,650 square feet on a parcel. A typical residential parcel in Berkeley is about 5,300 square ft thus commonly three homes maximum.

Despite the zones except R-1 being “multi-family” areas, a supermajority of parcels under them haven’t seen any homes built on them in the last 50 years. Partially because the city passed an ordinance in 1973 which made getting a permit extremely difficult — known as the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance. But zoning imposes more hidden restrictions on land such as floor area ratio or “lot coverage.” Within the above zones, only 35 to 45% of a parcel can be developed into housing.

While the prohibition on apartments in Berkeley’s eastern and northern neighborhoods dates back to the city’s founding developers and bigoted real estate interests, the southern and western part of Berkeley was downzoned from apartments to mostly single-family and duplexes in the 1960s and 1970s by minority and white middle class homeowner groups. Amid urban decline, many homeowners wanted to keep out renters and apartment buildings to make their property values go up.

In the 1970s, left-wing activists opposed the construction of dingbat apartments and allied with liberal homeowners to pass the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance (NPO), which effectively finished off housing construction in the city. Berkeley went from adding about 400 homes a year in the 1960s to zero in the next 20 years. The ensuing housing shortage caused mass homelessness, the rise of gentrification displacing Black residents and severe student housing struggles. Since the 1990s, many progressives and liberals in Berkeley have tried to rectify the issue.

After Berkeley City Council first announced their intent to abolish exclusionary zoning, and initially proposed four-home zoning citywide, it faced immediate challenges. It was decided not to impose any additional low income housing requirements beyond the city standard of 20% if projects exceeded 5 or more homes. Some had wanted a 25% requirement as the NPO once had, but everyone remembered that almost no homes were built under that level without public subsidy. It was deemed unfair to tax small housing construction by average property owners while single-family developers made nothing afforable.

The bigger issue was setbacks or mandates for front yards. Preservation groups such as Berkeley Neighborhoods Council adore the suburban uniformity of houses with large lawns and mandated front and backyards. I don’t. I’m fine with urban rowhouses and prefer parks for communal greenspace. Backyards usually function better as private open spaces and most front lawns go unused, waste water, or are gated up. But after a secondary home was built in South Berkeley right up to the sidewalk, homeowner groups made a very loud protest for setbacks in any new zoning and the city’s Planning Department and Commission abided.

The biggest issue was and is fire zones. Most of the wealthy single-family zones are located within active fire zones or are mostly in areas that were affected by the great firestorm of 1923 — known as the “hillside overlay.” These neighborhoods have small streets and sidewalks with parked cars sitting on top of the sidewalk, making evacuation difficult in the event of a firestorm.

Hillside neighborhood groups and council members were adamant about prohibiting multi-family housing in these areas to keep the population low. But doing so would leave the vast majority of Berkeley’s highest income and most segregated opportunity neighborhoods untouched — defeating the point of reversing exclusionary zoning. Moreover, market realities many “single-family homes” in the hills are overcrowded with renters and multiple large families.

While staff at the Planning Department proposed exempting Berkeley’s wealthiest communities, the Planning Commission (the Planning body appointed by the city council) surprisingly removed their exemption. The hillside overlay (based on the antiquated firefighting of the 1923 great firestorm) is unusually huge, stretching well to the wealthy parts of the flatlands with wide roads that are clearly not at severe fire risk. In contrast, the state of California considers only the very high up sections east of Grizzly Peak Blvd. to be an actual fire zone.

It’s never been articulated why single-family housing should be maintained in areas at risk of succumbing to wildfires. Rather than defend the status-quo, the city should mandate existing homes within the actual fire zone be fire-defensible homes. Follow neighboring Orinda’s lead and fine property owners who do not engage in vegetation management and eucalyptus removal. Stop allowing mansions to be constructed in the hills. Street parking should be completely prohibited rather than letting evacuation routes be clogged with parked cars.

Ultimately, the Planning Commission overruled the Planning Department’s proposal to exempt the hillside communities. (Note: the Planning Commission is appointed by councilmembers to while the Planning Department are hired staff).

Here is the latest product of Berkeley’s “Missing Middle” upzoning, soon to be certified or rejected by the city council. The city has moved away from mandating citywide four-home zoning and moved to “form-based” zoning with uncapped density.

All density limits for the R-1, R-2 and R-1A zones have been removed. Any number of homes can be built, provided the building does not exceed 3 stories, with a 4 foot side or rear setback and 15-20 foot front yards. In practice, this will allow about 6 to 10 homes on most city parcels with landscaped front yards.

If the builder makes 15% of the homes for very low income households, 24% for low income households or 44% for moderate income households, the number of homes allowed will increase to upwards of 9 to 15 homes under state law. Under Berkeley law, 20% of homes for projects with more than 5 homes must be sold or rented to low income households. Any project at or over 5 homes will automatically be entitled to 3 to 5 additional homes.

The city will conduct historical census of all structures within the city, particularly if they’re likely to be demolished. This is good policy and how all cities should approach landmarking, rather than allowing anyone to bring landmark petitions only when new housing is proposed.

Allow 60% of a parcel to be developed, up from the 30 - 45% standard. No floor area ratio requirements.

No parking is required per the city’s climate change anti-driving policy. If a builder chooses to add parking and they’re located 0.5 miles within a transit corridor, they are limited to one space for every two homes. Bicycle parking and transit passes are encouraged.

The parking provision is particularly nice because the revolt against dingbat apartments in the 1960s was motivated primarily by how ugly they were. Massive, ugly parking lots and car ports built with most mid-century Berkeley apartments was entirely the fault of the city mandating parking spaces. We need homes with people riding public transit and bikes, not parking lots.

— Council Politics —

The end of exclusionary zoning is by no means guaranteed. As many know, Berkeley’s been riled in ugly drama, recently. Councilmember Rigel Robinson, who was one of the four council members that sponsored the anti-exclusionary zoning item, resigned last month. So too has Councilmember Kate Harrison, who resigned stating her disapproval of high-density housing being built in the city.

With the 9-person council down to 7, I’m certain there will be two no votes on the current plan or “yes votes” with substantial amendments to it. Councilmember Susan Wengraf who represents the Berkeley Hills, has staunchly been opposed to any attempts to allow population growth in the hills. Councilmember Sophie Hahn, who represents the northern single-family districts Northbrae and Thousand Oaks, is unlikely to support without the hillside exemption which extensively exempted those neighborhoods.

Under the city’s charter, five yes votes are needed to pass the proposal. Mayor Jesse Arreguin, West Berkeley Councilmembers Terry Taplin, Rashi Kesarwani are likely yes votes. Southern Berkeley council members Ben Bartlett and Mark Humbert might face pressure. Humbert represents the wealthy district which created exclusionary zoning — Claremont and Elmwood — and has long stated his disapproval of it. But he still represents the wealthiest area of the city and as pressure ramps up Humbert could use support. Councilmember Bartlett was also an original sponsor and has a pro-housing track record, but his district has activists who vocally opposed to denser housing at Ashby BART station and the Adeline corridor, so he’ll need to see big support from residents as well.

No council meeting has been scheduled yet but Berkeley residents should email the city council at council@cityofberkeley.info with the title “Support Missing Middle Housing.” Request that the city council should pass the Planning Commission’s proposal “as is.” Feel free to discuss your own housing woes as reasons for why it should be passed. These letters will be filed by staff into the future item and can make or break Missing Middle housing in Berkeley.

— Final Thoughts —

With demand for housing so backed up, most of these homes will be bought by upper-middle income families or rented by lower-middle income families and students, or used by multi-generational families to house relatives. The fact is most middle income families are non-white, with around 30% of Black and Latino Californians being middle income. These are the families that once lived in Berkeley until skyrocketing home prices and the housing shortage took them out of the city. This zoning brings Berkeley back to the 1960s in land use allowances but with much higher protections for historic homes and existing renters.

Most properties to be replaced will undoubtedly be single-family homes. Demolishing existing multi-family apartments is economically unfeasible under the city and state’s rules that they must be replaced at the same rent or made low income if vacant. It’s worth remembering that the gentrification crisis Berkeley’s been dealing with for 50 years has seen the city’s non-white and working class communities shrink in neighborhoods not building housing. The only areas in Berkeley in which Black and Latino residents are growing, are the districts building housing and UC student districts.

Lastly, mostly wealthy homeowners have taken advantage of rezoning laws while lower and middle income homeowners have struggled to build on their property. They don’t have access to the capital necessary to get approvals or finance increasingly expensive development. Access to capital to build homes for non-rich homeowners is the next issue council needs to confront when discussing where “Missing Middle” housing goes next.

I have come to believe that (covenant) affordable housing / inclusionary zoning is Bad, Actually. Fundamentally the entire concept relies on the existence of a shortage. It assumes there are excess profits on market-rate units, which can be re-directed to subsidize the covenant units. If you have a 20% inclusionary zoning rule, what you're saying is you will never allow the housing shortage to get less-bad to the point that excess profits stop covering 20% covenant units stop being available.

We should want housing to be so abundant that the rent you can collect on new market-rate units only barely covers costs (including a fair income for the builders), with no excess.

Do I understand correctly that currently in Berkeley, for projects of six or more 20% of the units must be low income? That’s very high. Have for profit projects been built under those conditions? Do they all use the state density bonus to (in essence) lower the percentage of required below market units?