In Defense of Shattuck: Housing in downtown Berkeley

I respond to SF Chronicle contributor John King regarding his criticisms of Berkeley's housing development boom downtown.

John King, an architecture critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, wrote about his discomfort with high-rise apartments built in downtown Berkeley and it’s future ramifications. I like King but I think his piece warrants criticism as it broadly maps onto the larger California housing discussion.

Issue #1: The State vs The City

King acknowledges that downtown Berkeley housing development has long been stifled by anti-development opposition, primarily motivated against highrises and height issues. But he’s concerned that the power of state laws passed in recent years will prevent Berkeley from shaping its urban form and determining what housing it wants.

One reason for the shift is that more Berkeley residents — and those in other Bay Area cities — now accept that the region needs to provide homes for all types of people. But there’s another factor at work: Legislators in Sacramento have passed a raft of bills to make it easier for developers to build residential buildings, meaning that cities like Berkeley have little choice.

Little choice? Berkeley has plenty choice, actually. The state isn’t writing Berkeley’s zoning maps which facilitate where and how development occurs. For the very first time it has nudged cities like Berkeley to comply with fair housing which Berkeley ultimately did a month ago. But the downtown development of the last 20 years hasn’t been enabled by the 2023 housing element review. Even the density bonus, which allows developers to build more housing if affordability units beyond the state requirement are added and which King implicitly derides, has been regularly used since the 1990s.

Cities have always had the power to determine how housing is built in their town via their zoning maps which they can change at any time. As I covered recently, all new housing state laws have largely done is force Berkeley to abide by its own zoning rather than allowing city council and the zoning board to arbitrarily reject zoning compliant projects. Why is this significant? Because Berkeley citizens voted twice in high profile contentious battles for more housing development in downtown in the last decade. Moreover, Berkeley has debated downtown housing as the only politically palpable place to have new homes since the late 1980s. How many more years do Berkeleyans need to debate this topic before the losing side accepts they’ve lost?

John King takes issue with another state law which mandates that no more than five public hearings can be made on a residential development project. I doubt its incidental that the author of that law, Nancy Skinner, comes from Berkeley. She undoubtedly saw first-hand how endless meetings are effective tools to block housing in place like downtown Berkeley.

In 2010 and 2014, Berkeley voters overwhelmingly approved a zoning plan that allowed for three high-rises for downtown. When the first high-rise apartment was proposed, an arrogant and organized NIMBY opposition who believed voters didn’t know what’s good for them dragged it through 37 meetings. I was there: nobody ever changed their minds; it was an endless contest of posturing and speeches with no end in sight. It was eventually approved with a whole host of financial concessions far beyond a standard development project that didn’t change the NIMBY’s opposition but did what it was designed to do: make the project infeasible.

King makes a brief reference to this, but doesn’t reflect on it at all in relation to the state law limiting hearings to 5 meetings. Out of the 37 meetings on Harold Way, at what point was the project changed for the better? Instead of potentially 100 low income homes on-site and in our trust-fund Berkeley got zero. The oh-so historic movie theater to be preserved that was long in decline and would’ve been replaced with a modern IMAX theater, announced closure shortly after the lockdowns. What did all that energy, staff time and salary paid for by Berkeley taxpayers amount to? Not a damn thing.

The battle of Harold Way was the genesis of the modern YIMBY movement in Berkeley and the East Bay, because a generation of people saw up close that the NIMBYs didn’t actually want any of these benefits to materialize. The NIMBY’s true, ulterior motive was revealed in their joyous celebrations in newsletters, their newspaper and tweets when the housing fell through.

The voters a decade ago explicitly approved 3 high-rises in downtown Berkeley and only one was ever built — a hotel. The two housing projects were sued and obstructed endlessly, one into oblivion and the other has yet to break ground years after approval. Both of which were fought over viciously while curiously, the hotel high-rise received tax breaks (in total contrast to the unusually high requirements and community benefits for the residential projects) and no NIMBY cared to even fight it like the downtown housing.

Isn’t it odd some people only get mad around here when it’s housing?

Issue #2: Bulky Apartments

King’s next issue is the bulkiness of the new apartments. He would prefer slimmer and sleek buildings, with more creative designs over the dense building blocks with generic facades. This is a common criticism lobbied at “5-over-1s” (five stories of wood frame housing on top of 1 concrete ground floor) apartments in many American cities. Too bulky and ugly; designed to cram in as many apartments as possible to make money at the expense of artistry.

The issue isn’t height, which people tend to fixate on (wrongly). It’s bulk. Developers and their planning consultants figure out how much space they can jam onto their site using the new bonus, then wrap it in “architecture.”

Oddly absent from King’s article is the glaring reason 5-over-1s and bulky buildings are so popular and homogeneous in the United States but not elsewhere in the world: double-loaded corridors a.k.a two stairwells.

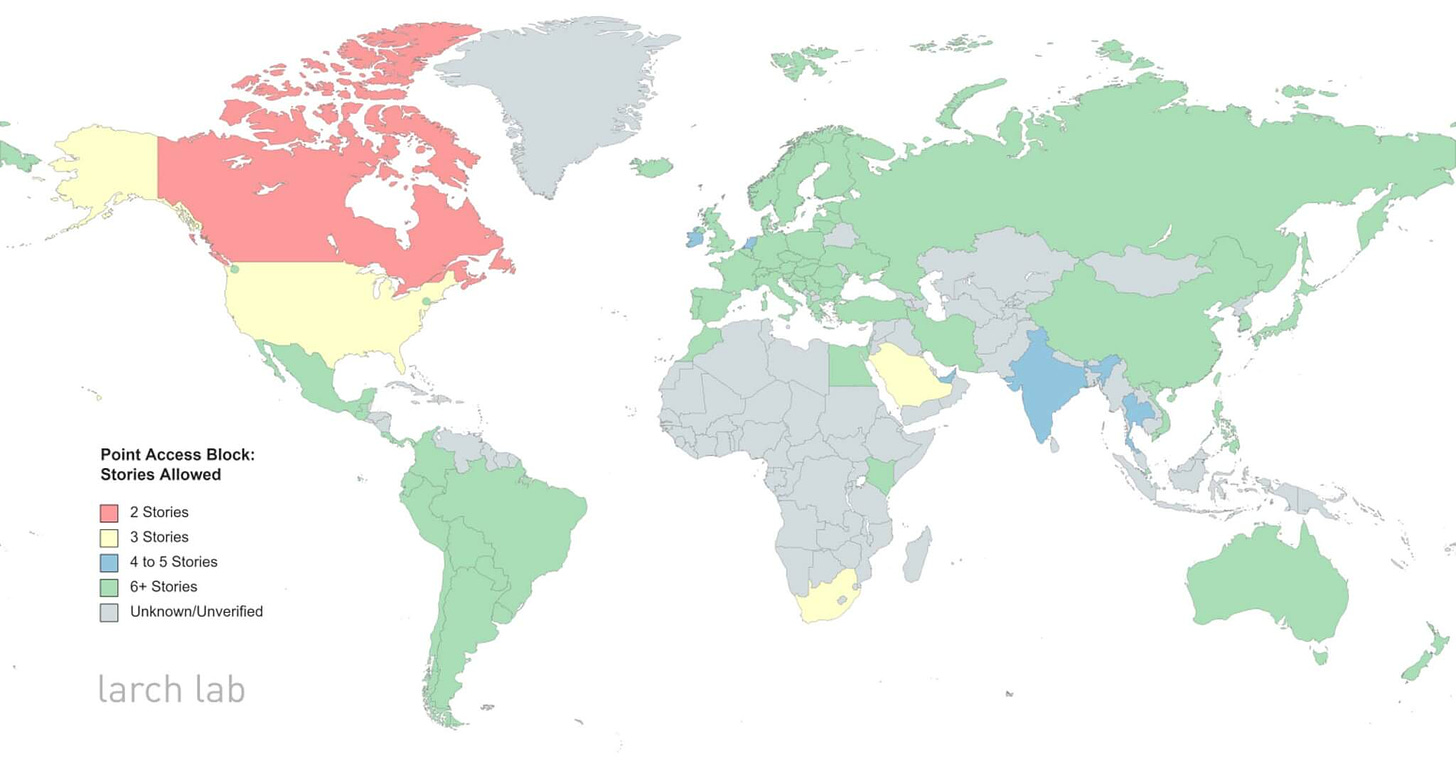

In most the United States and Canada, new apartments beyond a few stories must contain two stairwells on opposite ends in the event one stairwell is made inaccessible due to fire. The problem is that there’s isn't much evidence that having two stairwells increase fire safety — hence why the rest of the world doesn’t require double-loaded corridors (see map above). In Europe, Latin America and Asia, new single-stair apartment complexes are common, and most of those countries don’t have higher rates of residential fire deaths than the United States.

The byproduct of the double-stair requirement is bulky, boxy apartment complexes whose dimensions must adhere to parallel stairwells, making narrow and unique dimensions impractical. You can read about it in great depth here. But this is a significant force for why apartments are so block-like and redundant in cities across the United States.

The stairwells have to be wide and there must be two of them, which means a significant portion of the floor area generates no revenue. Developers usually need at least 90% of the floor area to be profitable for commercial and/or residential space, on top of space mandated for open space by city planners. Thus, developers engage in expensive acquisitions of parcels and spread out the width of buildings.

Architects generally dislike double stair requirements because it shrinks the size of new dwellings as they’re cut off by the double stairwells. This is often why family-friendly housing remains exclusively within single-family construction which is exempted from double-loaded corridors, while new multifamily housing is so studio and 1-bedroom oriented.

Climate researchers also dislike double-loaded corridors because it makes natural ventilation from one side of the building to the other via opening opposing windows impossible. Developers must install expensive cooling systems which are carbon intensive. (I personally do not have strong feelings about double-loaded corridors and would like to see more research on their fire safety.)

But John King is an expert in architecture and this is a big debate among architects. California Assembly member Alex Lee (D - San Jose) has proposed legislation, AB 835, that would study transitioning California’s building codes to the international standard of single-stairwells. I’m surprised that at no point he mentions this as the cause of bulky buildings which are lobbied at every new 5-over-1 in the country, rather than proclaiming developers in Berkeley are just being oddly and uniquely cheap with bulky architecture.

Issue #3: Town Vs Gown

There’s another issue, one raised by growth critics like the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association [BAHA]: The new structures, in large part, would hold university students, erasing the dividing line between town and gown once and for all.

Oh god, no! That sounds horrible. College students living at the front door of the college they attend, in a town that solely exists and is famous because of said college? Good heavens, what will Berkeley do? We can’t just export UC and Berkeley city college housing needs to Emeryville, Oakland and Richmond anymore! Berkeley students may live . . . in Berkeley!

I truly don’t understand King and the BAHA’s point here. In case the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association and John King are too busy looking at buildings and haven’t noticed, there’s long been a rise in college students living in traditionally non-student neighborhoods. Students have gradually eased out non-students who inhabited older stucco apartments and multiplexes due to the dearth of student housing.

Moreover, the “town” of Berkeley has changed dramatically. What was once a town full of families, young people and working class people with a variety of jobs, is now more of a wealthy retirement community with a few wealthy tech folks who can buy single-family houses. The families of Berkeley have gradually moved away while new families have been blocked from coming here, so our schools have been closing in response to the decline in district enrollment. (Note enrollment is growing primarily in Dublin where significant amounts of homes have been built).

Nowadays you hardly see kids running around in Berkeley’s neighborhoods and commercial districts — just senior citizens. It’s a college town for Christ’s sake. Go to the South Bay and witness the blooming elderly population alongside a baby boom of young children. In contrast, Berkeley is a donut city of elderly and / or wealthy homeowners with a donut hole of 18 -24 year olds in the city center. Does that elicit concern from the Architectural Alliance or King?

Neighborhood groups should be applauding and rooting for the downtown development as it’s confining UC students to downtown and away from the neighborhoods. Whenever they sue it or whine about it they just ruin their own neighborhoods, but it seems their answer to the housing shortage is to just stop enrolling students at the nation’s #1 public university. Good luck, that’s the opposite of what Californian parents want.

Also, new housing outside of downtown has largely been aimed at seniors, enabling longtimers to cash out their houses, let a young family take it, and downsize into ADA-compliant facilities. If Berkeley were to allow more housing outside of downtown, many seniors would downsize and stay within their community.

—

I won’t lie. I am sympathetic to the general dislike of some bland new apartments. I really like the work of Trachtenberg Architects who are making some of the most creative facades for their apartment complexes. But they’re still confined by the planning requirements that create bulky buildings. Additionally, Berkeley only has several developers building wide swaths of our housing stock since city politics is quite harsh on amateurs. Hopefully state laws codifying objective approvals where compliant projects are ensured approvals will open the door for more creative architects.

King talks a lot about how downtown Berkeley is changing, and references cultural things that will be lost with new apartments.

. . . gone will be the ecosystems that fostered the varied scenes now found along Center Street and the McDonald’s block of Shattuck. There might be new spaces but there won’t be the old rents, the funkiness of each space evolving at its own pace.

I remember downtown Berkeley in the early 2000s and it was a ghost town. You could find street parking at any time of day because people seldom went there — only passing through. When I was in middle school all the school kids hung out on Fourth Street or Solano and never went to downtown. When my siblings went to Berkeley High in the 1990s they all hung out on Telegraph. Few cared about Shattuck.

The Shattuck of today is such a vibrant, fun place; more lively than ever before. I see young kids hanging out around downtown, eating at Slivers pizza and doing activities in Constitution Square. The newest hippies, runaways, travelers and the unhoused selling things, playing games and chatting along the sidewalks and benches between Allston Way and Kitteridge. A lot of elderly couples getting dinner and packs of seniors talking loudly as they stroll along Shattuck from the bars and eateries.

Berkeley High school kids barely venture to Telegraph anymore. They spend all their time now on Shattuck. College students are getting boba tea, going to plays, concerts, or going out on dates to some of Berkeley’s best restaurants. And the Census shows that downtown is one of the only neighborhoods increasing in diversity. While the rest of Berkeley loses its Black population, frozen in time with their anti-new housing zoning, downtown’s Black population has grown to the highest level in history and they’re majority non-students.

King frets that some of these dense homes put up by profit-seeking developers will be derided by future generations. I honestly doubt the next generation of Berkeleyans will be pining for the auto shops and parking lots of old most of these apartments replaced. I remember the big battle for the Trader Joes building at MLK Way and University Avenue. Very few of those doom-and-gloom predictions came true for what is now a vibrant sidewalk instead of an auto shop parking lot.

Honestly, what I see veiled in a lot of the complaints about downtown Berkeley’s housing boom and Berkeley NIMBYism in general is the feeling of getting old. Though I’m 26, I quite sympathize with it. John King hints at his discomfort with time, lamenting about the supposedly vibrant McDonald’s corner and Spats bar.

The new hip bars like the Berkeley Social Club which attract crowds on University Avenue regularly, are not the same hip bars that were in their prime 10 years ago like Kip’s or even 20 years ago like Spats. We all age and it’s uncomfortable. New experiences are forged and oftentimes we’re not in on it so we get sad. A lot of these downtown critics and NIMBY haters walk around the crowded streets of Shattuck, envious about the fun they see people having.

Yes it’s sad we lost longtime businesses to the post-pandemic realities (I still pray for the return of a late-night cafe like Au Coquelet), and we can hope that the new businesses to come foster as much street life and excitement as the ones of old. The Victory Point Cafe has that potential!

But time is linear. Preservationism must evolve beyond the Peter Pan syndrome of trying to force future generations to share your rose-tinted memories. Berkeley has obsessed so much about preserving buildings we've failed to address the loss of artists, creatives, teachers, young families and service workers gradually priced out for over 40 years.

When our plans to grow our future are constantly undermined by a minority of old timers who cannot accept that Berkeley won’t look the same tomorrow as it did yesterday, then it is good that our democratic representatives at the state and local level enshrine the electorate’s will.

Today, Berkeley is producing more subsidized, low-rent housing than ever before since World War 2. It could be doing a lot more but NIMBY voters voted down taxes to fund it in November so we’ll try again. Berkeley is also making a big dent in the housing needs for college students and could be doing more for non-students and seniors if it were expanded modestly into the neighborhoods.

Sadly, it’s decades too late.

—

Good on you for sitting through 37 (or most of that number) meetings. That's commitment to a story / cause.

Your article is great. Did you share it with John King yet?