People Don't Understand Affordability Requirements

Mandating low-income housing in new developments sounds great but without subsidies, it's a flop. We've known this for decades.

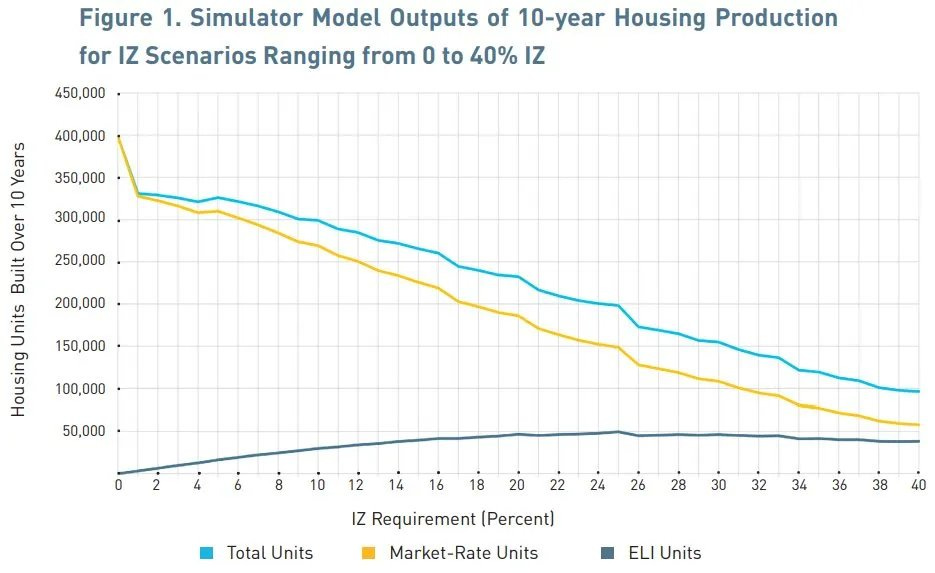

Shane Phillips, a researcher at UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, released a tool (using Terner Center at UC Berkeley’s data) that show the trade-off of mandating higher percentages of low-income housing against the production of market-rate housing in privately financed developments. As the percentage of inclusionary units increases in new developments, the number of market homes declines. Most importantly, once an inclusionary requirement reaches 20 - 25%, it ceases to produce additional low-income units and decreases the number of low-income homes built because the volume of market housing overall is less. A higher percentage does not mean the quantity, the real number of low-income homes, is higher. You’d be surprised how many in housing discourse are mathematically challenged by the concept of fractions.

Inclusionary zoning started in the early 1970s in California to encourage suburban communities to integrate by mandating a percentage of low-income housing in new rental developments. When President Nixon froze public housing construction, some urban communities innovated inclusionary zoning as a supplement. It became popular among progressive jurisdictions to make middle-class-oriented rental housing more low-income.

Within ten years of implementation, pundits, researchers and its many original sponsors conceded it didn’t build much low-income housing. Here’s Donald Terner, Housing Director under Jerry Brown and one of Inclusionary Zoning’s original sponsors explaining it’s primary problem upon roll-out.

Local government offers the developer incentives to make [affordability requirements] economically feasible, says Terner. Without greater density, government loans, land write downs or parking regulation waivers, inclusionary zoning was "well-intended nonsense."

— SF Examiner, 2/9/1986

An excerpt from a book on the East Bay Area’s left-wing economic revolution in the 1970s explains how the socialists in Berkeley who introduced one of California’s first ordinances knew their 25% inclusionary requirements weren't feasible.

The requirement that low-to-moderate income housing be provided in any development was included to guarantee that new development would not be exclusively for wealthy residents. But proponents also understood that no private, speculative developer would either desire to provide lower priced housing, or be able to afford such inclusions without subsidies.

Inclusionary zoning is, as Donald Terner said, a well-intended tool sometimes weaponized by exclusionary communities or proponents to act as unofficial housing moratoriums, with voters often none the wiser. Most people when asked what percentage of new developments should be low-income have no idea of the financial feasibility or where funding is coming from, so whoever says the highest number wins.

That’s how you get results like Portland’s, where a 20% inclusionary policy that promised 555 low-rent homes a year resulted in only 189 a year. In 2016, San Francisco voters passed a nice sounding 25% affordability requirement. The Controller’s Office predicted it would create fewer low income homes, but many politicians and activists dismissed this as neoliberal fearmongering. Like clockwork, the city had a 75% reduction in low income housing funding because the revenue they get from housing construction tanked just two years later. Finally admitting it didn’t work, the Board of Supervisors had to reverse this policy last year as homelessness skyrocketted and construction was completely unfeasible. A painful lesson in mathematics that making percentages higher does not inherently make the quantity higher.

While San Francisco’s case was unintended by voters, some exclusionary communities intentionally abuse inclusionary zoning knowing exactly what they’re doing. Atherton, the wealthy Silicon Valley suburb, mandated 25% inclusionary as a way to subvert state law forcing them to build homes. Republican-run Huntington Beach has announced its intent to do the same.

Let's be honest: there’s nowhere in the United States or any city on Earth where unfunded mandates for subsidized housing in new developments produce a lot of low-income housing. Most places with high inclusionary rates are among the most unaffordable cities in the world and produce the fewest homes.

Inclusionary zoning higher than 5% or even 10% is only feasible or profitable in very expensive markets. San Francisco’s own Planning Department found that with high inclusionary requirements, the only place building housing will not be a net-negative in revenue is in the highest of high rent neighborhoods, only. Rents are set by the market, translated from what enough people are willing to pay, and market rents must provide enough revenue to exceed the cost of construction, debt service and profit margin.

Anything approaching 20% inclusionary housing mandates mostly materialize in places where projects are profitable enough to subsidize those inclusionary units, and those projects are usually expensive luxury housing. That’s why most of the yield from inclusionary zoning is coming from places like downtown Los Angeles or San Francisco rather than middle class areas. The latter’s rents aren’t high enough to cross-subsidize 1/5th of the homes.

For example, San Francisco’s real estate is dealing with two events: one is high-interest rates meant to deter so-called over-construction, and the second is the outmigration of higher-income professionals from the city. There are enough luxury condos and high-end rentals in downtown S.F. relative to demand, so building went from being small to almost nothing. While middle-class developers can build in cheaper places like Texas or Arizona, only high-end, luxury developers can afford the cost of construction in San Francisco and much of California. When the median new home in San Francisco costs well over $1 million per unit to build, thanks to high material costs, high-interest rates, and an expensive approval process, you cannot price a home any lower than that.

We should look towards Vienna, Austria for how we want to approach integrated housing development. American puff pieces about Vienna never engage with the substance or specifics of how Vienna achieves low-income housing ratios as high as 40% in new developments. Chiefly, it’s not an unfunded neoliberal mandate expecting developers to provide public goods by incentive. Vienna builds social housing via a 1% income tax towards a dedicated housing fund. The municipal agencies then incentivize competition among client developers with these funds. This is also why development looks better in Vienna than in most American cities (that and building regulations are modern and more evidence-based). Whereas inclusionary zoning essentially taxes new housing to pay for subsidized units, Vienna taxes the city’s wealth to pay private developers with loans and land leasing in exchange for high-quality, social housing on the city’s terms.

The unfunded mandates version of inclusionary zoning we practice in expensive U.S. cities doesn’t work at producing sizable amounts of low-income housing, and we knew that within years of its creation. It was a neoliberal solution to dwindling HUD investment of public housing and unsuccessful integration. It’s as silly as mandating grocery stores sell 20% of their food below market prices to solve food insecurity or 20% of gas stations to sell below market fuel to solve transportation. The debate should be on whether to subsidize the market producers, create public goods or subsidize people in need.

I don’t believe inclusionary zoning is bad. Once we acknowledge that subsidized housing requires subsidies and taxing new housing is sub-optimal over taxing income or land, which are the actual instruments of high rents and home prices, we can start to realize some solutions. Realistically, unfunded inclusionary zoning requirements should not exceed 10% of total projects and should be traded for swift approvals, greater density and fee exemptions. Our most successful inclusionary programs are density bonuses, so let’s build off that. In the 1990s, some California cities — including progressive Berkeley — approached inclusionary zoning by offering loans to developers that they would pay back with realized rents. Smart!

Inclusionary zoning is not an affordability policy, it's an integration policy that is constantly misused. Unfunded mandates can’t replace the hard work of taxing monied interests — chiefly landowners and wealthy residents, which includes all real estate holders as well as developers — to pay for public goods. Cities wrongly depend disproportionately on the borrowed capital of multifamily developers, not even house flippers or single-family developers, to subsidize housing. Rents and home prices derive not from who builds housing but who owns housing and land under it. We should subsidize our low-income housing by taxing landowners and the high incomes inflating housing costs, not tax what we lack, which is housing.

DO - This is an example of why you are one of my favorite thinkers and essayists in our local housing discourse. This article moved me from free to a paid subsriber.

IMO, the unintentional and willful ignorance around housing math and lack of understanding about basic housing policy is our largest challenge to effective local housing policy. The hundreds of comments to Oaklandside's recent article on Oakland's current consideration of implementing an IZ policy are an example. I shuddered at the mountain of misinformation in those comments and kept it moving. It's hopeless.

=========================================

WHAT BOOK IS THIS FROM?

An excerpt from a book on the East Bay Area’s left-wing economic revolution in the 1970s explains how the socialists in Berkeley who introduced one of California’s first ordinances knew their 25% inclusionary requirements weren't feasible.

The requirement that low-to-moderate income housing be provided in any development was included to guarantee that new development would not be exclusively for wealthy residents. But proponents also understood that no private, speculative developer would either desire to provide lower priced housing, or be able to afford such inclusions without subsidies.

================================

A couple of quick comments and questions:

- Vienna talk is all the rage these days. Comment/question on Vienna - Austria has the 1% dedicated income tax to fund housing. This isn't a tax on wealth as you write above - this is a tax on income. Is there an income level below which Austrians don't pay this tax?

- Vienna has a lower population now than it did in 1880. In fact, Vienna's population declined 25% from its 1920'ish peak. Local govt was able to acquire vacant and abandoned land at cheap prices. That's not the case here and now. To implement Vienna style social housing, we have to fund not only construction and maintenance, but land acquisition in a built out Town. What's the math on that? Is there an appetite for another wave of eminent domain powered "urban renewal" in the flats? I thijhk its safe to say that our leafier neighborhoods won't be razed for Viennese style social housing apartment blocks

- Finally, as always, I challenge your notion that land ownership equals accessible wealth for lower income marginal homeowners. A friend's mom is a retired teacher with a house in East Oakland. Her pension doesn't cover her living expenses (healthcare is high - this ain't Vienna), and her kids had to borrow to cover her property tax that was due today 4/10. Increasing her property taxes not only directly increases her housing insecurity, but the ripple effects increase displacement & housing security in EO, if she has to sell her house and relocate to a lower cost region (i.e. Atlanta)

Keep doing the thinking!

All of this is spot on as someone living in a 50/50 set aside luxury building with a lot of caveats and culture shocks. We should be subsdizing housing and small neighborhood service business sites as a government and that doesn't take away from a private market that wants to use skyscrapers as ATMs and toys.