The Allure of San Fran-Sicko

Let's have some frank conversations about homelessness. No platitudes here.

Everyone is handing this book out. Michael Shellenberger’s “San Fran-Sicko.” My liberal book club handed it out. San Francisco’s Fire Department distributed it. I saw people buying it at the bookstore. It’s a very alluring book. It’s quite a convenient book.

But it’s a very stupid book. It’s a very simple book that obscures its stupidity with exposé-like detail.

Pulling apart the specific claims has already been done in significant detail, even by my own employer. To recap: Shellenberger tries to discredit the ‘housing first’ model of reducing homelessness by positing that homelessness is a byproduct of liberal city tolerance of drug addiction and mental illness.

Shellenberger doesn’t outright say that housing costs don’t fuel homelessness — which is wise because the existing body of data has all but conclusively shown that it does — but he tries to stay away from blaming housing unaffordability by noting it’s in progressive, liberal blue areas this is a problem and not red states.

Shellenberger’s popularity comes at a time when the homelessness crisis appears to grow exponentially while Californians are suffering from tax fatigue and are dedicating huge portions of their incomes to housing costs. It’s a very common and understandable sentiment that average housed people believe they’re spending money on services and housing for the homeless, yet encampments grow more and more every day.

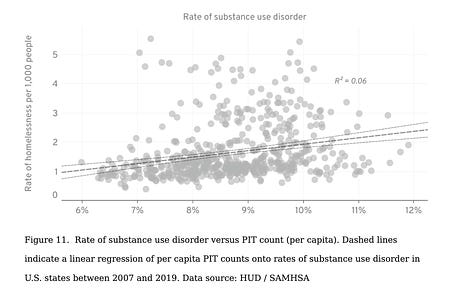

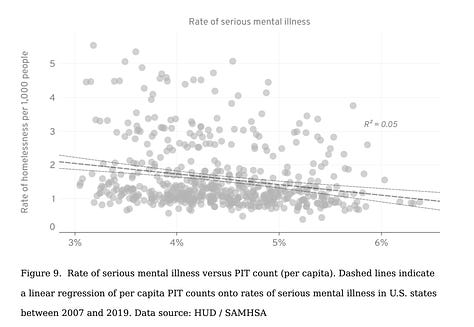

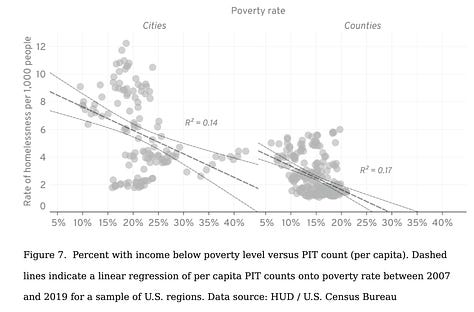

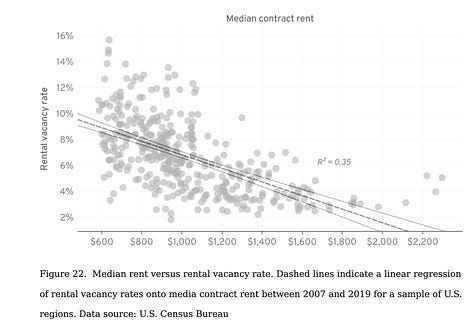

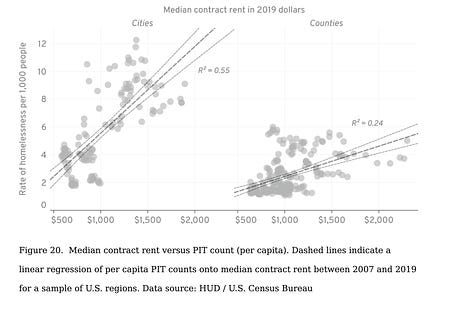

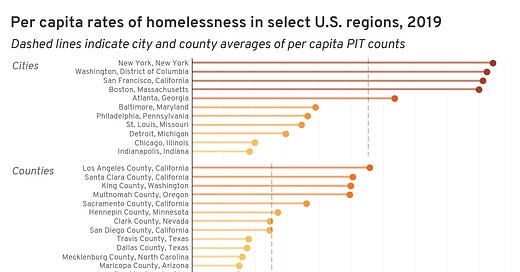

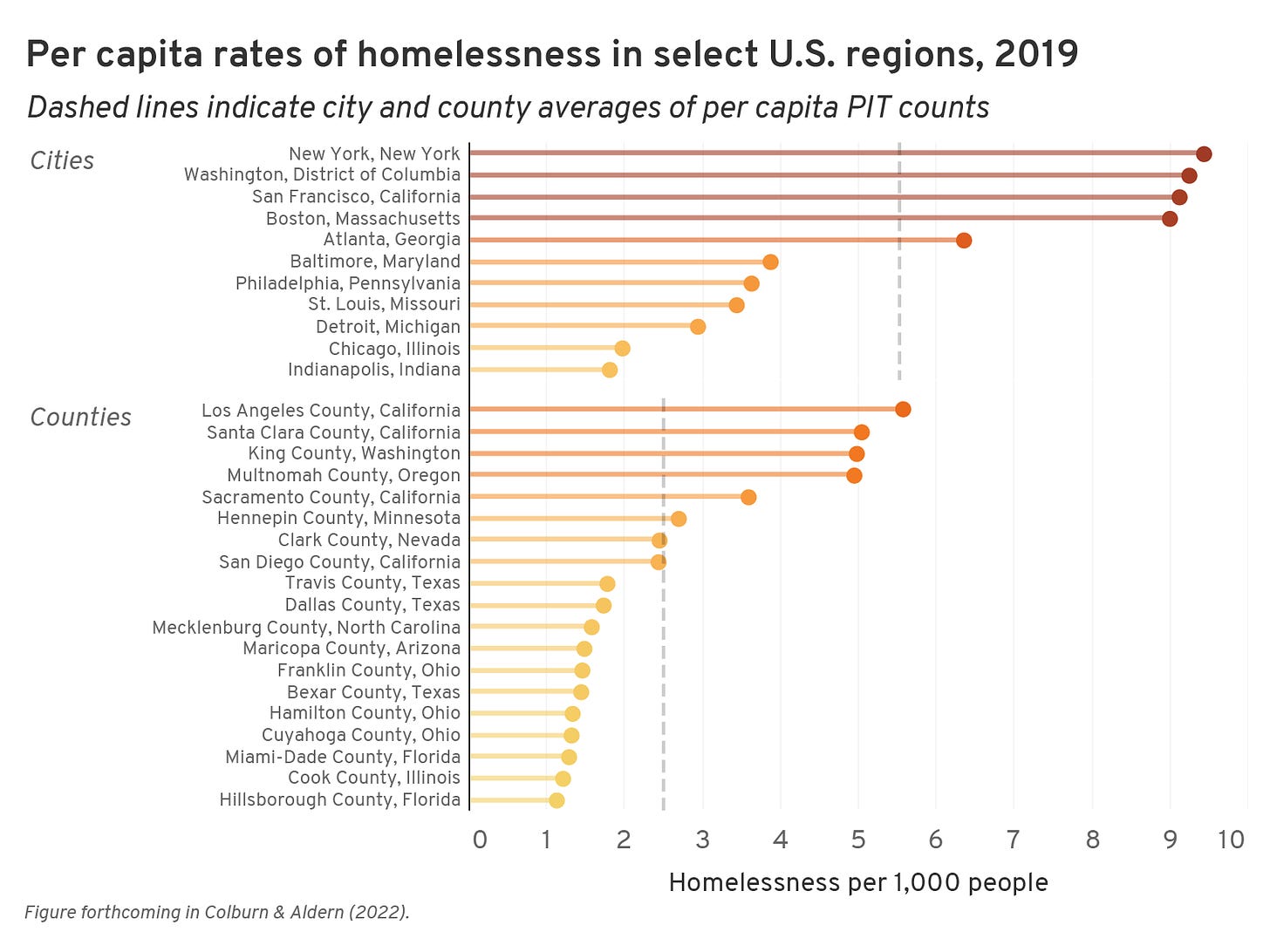

But the data as compiled by two UC researchers found that addiction, mental illness and poverty were not remotely significant factors in causing disproportionate homeless in major cities and coastal states. If they were, then the Midwest and the South would be leading in homelessness — with Mississippi the impoverished state and West Virginia the addicted state. If it was about warm weather, the Sun Belt would lead in homelessness not New York City.

The analysis only found two clear causes for high homelessness in US cities: median rents and vacancy rates. The lower your vacancy rate is and the higher your rents are (which are directly related to each other), the more homeless people there are. Not even rent burden was a factor in homelessness discrepancies, as low incomes in low rent places means support systems are more effective, whereas in California, we’re spending three-quarters of a million dollars to build a single subsidized home. Mental illness, drug abuse, alcohol use and poverty rates did not correlate with high homeless populations.

So if this data is evident, why aren’t we doing anything about it? Well, because half the population’s home equity depends on us not doing anything about it. As Jerusalem Demsas explains, Democrats have been bad housing leaders because housing, unlike other issues such as schooling and healthcare, is not pursued with evidence based solutions.

In the housing debate, you realize early on people arrive at their solutions (“development is bad”, “apartments aren’t climate friendly”, “homelessness is a personal choice”, “too many people is bad” etc) and work from there. Democrats and Liberals realize that housing is one of the very few third rail issues where appeals to emotion about neighborhood integrity, earned property values and the virtue of homeownership are electoral necessities to win locally. Of course, in some coastal and urban areas they try to left-wash this stuff with platitudes about how new housing is a plot by developers or blaming gentrification on new housing with little evidence.

The sad part is that the liberal’s abandonment of empiricism on housing affordability only serves to hurt them and the unhoused in the long run as anti-homeless political backlash grows. Even progressive Democrats that are good on housing for the homeless are not as good at preventing homelessness or understanding how housing causes homelessness. People are mobile, and unaffordable housing and few vacancies will mean some people won’t have a home — it’s that simple.

Ok, says the skeptic: all these graphs and charts may be true but why don’t you people just admit, as numerous anecdotes highlighted by Shellenberger affirm, that there are some homeless people whose decisions and behaviors make them and keep them homeless? Why not admit that there’s some homeless people who don’t want to be housed?

Well, there are a few complaints and charges by people that the re-integration process of supportive housing can be excessively paternal and makes them not want to participate. Once a person has lived out on the street for a long period of time, it’s hard to readjust from a survivor back into a sheltered person. Sudden anti-hoarding rules, curfews, drug prohibition and pet rules can be quite imposing on people, and often makes them feel demeaned and trapped in the process. The answer there is to try and be flexible about supportive services, not abandon the whole project.

Stories and incidents like these are held up by the ‘right to be homeless’ activists, albeit a minority of the homeless, as evidence of the carceral aspects of housing first. I don’t think it’s bad to expose that these supportive systems don’t always work for everyone and can fail. But anecdotes like these are gleefully jumped on by anti-homeless pundits and right-wing opportunists using it as proof that the homelessness crisis is a behavioral problem and a choice.

I was getting lunch with a national homelessness reporter who explained this phenomenon to me. He told me if you’re an amateur reporter who just approaches an encampment with a microphone, the first few people to show up are idealists who will insist their encampments are about political resistance and other soundbites and that’s where most reporters stop. But if you stick around and actually interview the vast majority of homeless people there, especially the ones who have never spoken to media before, they’ll tell you simply they just want a home.

The common refrain from even well-intentioned liberals that “some homeless people don’t want housing” isn’t meaningfully true. When I worked for a nonprofit low income developer, my job was to write the software to analyze applicants for specific homeless and low income housing projects that on average contained forty units. The applicant lists ranged from 4,000 to 21,000. Lots of people wanted housing; we just don’t have enough to give them.

Another topic that Shellenbeger talks a lot about and is common in the liberal ethos on homelessness is not just the people who supposedly refuse housing, but the people who supposedly can’t accept it: the mentally ill and the addicted.

A lot of severely mentally ill people on the streets aren’t there simply because of the unaffordable housing market. Many have noted that there was a rise in the mentally ill population living without homes since the 1970s, and, yes, housing affordability and the decline of SROs was a big factor, but so too was de-institutionalization.

The rise of civil rights in this country gave way to not throwing people accused of being unwell into institutions which were prison-like places where rights and humane treatment were unheard of. However, since the backlash against the War on Poverty, financial support for people with severe disabilities is horrifically small. Even in housing markets where homelessness is much less an issue, people suffering from a disability or illness are usually living in substandard conditions, dilapidated homes or taken care of by family members who lack sufficient financial support to care for them well. Being severely physically or mentally disabled is often a one-way ticket to homelessness in any state, a shameful product of our Capitalist system.

Lately there have been more calls to quell the rise of street mental illness with non-housing solutions. Mayor Eric Adams of New York City has announced intentions to arrest and impose mentally ill homeless people into psych wards and hospitals en-masse — eliciting great backlash on social media and from civil rights groups. In California, there have also been calls to reform conservatorship laws so that people deemed unwell in court can be managed by family members or legal guardians.

While I’m fervently against throwing people into psych wards — I’ve had way too many close friends tell me how the experience increased their suicidal or unwell tendencies — I’m still conflicted on conservatorships in theory. I’m reminded of a mentally ill homeless man who incited mass ire in Berkeley when he sexually solicited a child at a park. In a sad moment, his relatives who live in another state desperately defended themselves in the story’s comment section about how they wanted to take care of their relative, but legal restrictions prevented them from doing so.

Should this man be put under the legal jurisdiction of his family? I’d like to think so. What are the alternatives? Should the state force him into housing and treatment? Is that not similarly carceral and against his civil liberties? Does imposing treatment violate his rights to freedom? If so, does treating a person who is clearly unwell deserve the same degree of punishment a criminal knowingly committing a crime gets?

This isn’t just a moral question under Capitalism, either. Even under relative housing abundance in a Communist-run system, there are some people who will fall victim to illnesses and abuses which will make housing for them harder to acquire. In the USSR, the government simply banned people from being homeless citing its constitutional right to housing. Alcoholics, drug addicts and the ill who could not hold down even a free place given by the state were officially labeled as asocial parasites and were incarcerated.

When I was a teenager I took care of my grandmother who had degenerated from Alzheimer’s. There was a period around stage 2 where she was too mentally ill to make rational decisions. Taking care of her was financially draining, as my mother was single and I had to watch her after school. If we had the money, we would’ve put her in assisted living care but nothing nearby was affordable. But now I wonder, at what stage in her illness did her civil liberties dissipate?

The conservatorship question is a hard issue for me to answer — especially as someone unlikely to have it imposed on but, like everyone, am one injury or bad life turn away from it being imposed on me. I can’t help but envision many people who are like my late grandmother — unwell and roaming the streets without support or control by their families. But I fear the abuse that could come about by allowing the judicial system to put a human being under the ownership of other people — even if its theoretically well-intended.

The reason I oppose Eric Adams’s plan, however, is that in the absence of an improved compensation system for families to take care of their loved ones — an improved supportive housing system in which the number of subsidized healthcare homes, end-of-life and supportive living care homes increases dramatically; and legal guardrails for civil liberties such as a clear offers for adequate care and safe housing — simply declaring homeless people ‘mentally ill’ and then incarcerating them will be the de facto response for politicians eager to appease the anti-homeless backlash.

For that reason, the focus must be primarily kept on what works for the vast majority of homeless people: housing first.

I’ve witnessed a lot of programs that help get homeless people suffering from mental health problems back on their feet. Shelter + Care, Continuum of Care, MHSA housing units and more. They all are housing units that come packaged with healthcare to support mental illness and resolve substance abuse. They work, we just don’t have enough of them even relative to what we invest in them because building costs are too high, zoning too limited, and the approval process too cumbersome. The more times a homeless person puts in effort only to lose out on a housing unit, the more demoralized they are to apply.

I know that the “people refuse service” narrative is popular among average people. Housing First is not glamorous for our American sensibilities. It does not appeal to the American middle class ideals of having to “bootstrap” your way to success. It does not fit into our fictitious ethos that our outcomes in life are entirely of our own doing rather than early life advantages and systems that trotted completely predictable paths. For that reason, Shellenberger’s quick and easy narrative will always be a popular one.

But there’s simply one proven method to reducing homelessness in the United States and it’s housing. Give your relatives and co-workers the empirical book “Homelessness Is a Housing Problem” this holiday season.

Schellenberger is a bad person. He decided to push a popular and false narrative to make money. He is Lawful Evil to the core.

I’m curious how other countries handle people in distress on the streets. Any peer countries out there who we should emulate? Heather Knight had an SF Chronicle story a year or two ago about visiting London and learning about their local initiative to intervene before someone spends a second night out on the streets.