Guest Article: The Incentive Problem At The Heart Of The American Justice System

How Financial Pressures Leave Us Under-Policed And Over-Incarcerated

Foreword: The following article is a guest post by written John Fawkes, a substack writer with a degree in criminal justice. I’ve accepted this guest article because I don’t want to foster an echo chamber, and its solutions do differ in some of my writings on American policing. After reading this piece, I think this is a important article on the fiscal incentives that instruct not only U.S. law enforcement but U.S. criminal justice and prison industry that I’ve seldom seen explained and is often simplified to “tough on crime” attitudes.

As usual, I am not endorsing all ideas proposed in the article.

Criminology, and the modern field of criminal justice, were invented in 1764. That year, the Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria published On Crimes And Punishments, a brief treatise in which he advocated reforming criminal justice systems along rational lines. His most notable stance, from a modern criminal justice perspective, relates to deterrence.

Beccaria argued that punishments should be intended primarily to deter future crimes rather than retaliate for past ones, and further, that three factors influenced the deterrent effect of punishment: its certainty, swiftness, and severity, in that order. Beccaria reasoned that increasing severity of punishment produced sharply diminishing returns on deterrent value, because people will simply become desensitized to severe punishment and have difficulty weighing it rationally when conducting a cost-benefit analysis of their decision to commit crimes.

This being the 18th century, Beccaria had no proof for his theory. Nevertheless, it gained wide acceptance and came to dominate theories of criminal punishment. Unlike most things that get accepted without proof, it turned out to be true, and the expert consensus, endorsed on a semi-official basis by the National Institute of Justice, strongly supports the primacy of swiftness and certainty of punishment over severity.

Despite the fact that basically everyone agrees on this, the United States largely does the opposite. The United States issues longer prison sentence– and is more likely to punish people via imprisonment at all– than other countries. Our prison population per capita is about five times the global average– we have 20% of the world’s prisoners with 4% of the world’s population.

According to the National Center for State Courts, the average time to disposition is 256 days for a felony case and 193 days for a misdemeanor. No court in the study meets the current national time standards. Current national time standards indicate that 98% of felony cases should be resolved within 365 days. On average, ECCM courts resolve 83% of felony cases within 365 days. The Model Time Standards call for 98% of misdemeanor cases to be resolved within 180 days. ECCM courts resolved only 77% of misdemeanors within 180 days.

In police officers per capita, the United States ranks 103 out of 146. This is actually worse than it sounds– most developed countries rank higher on that list, while most of the countries with the fewest police lack either the money to afford them, or lack effective governmental control over much of the country.

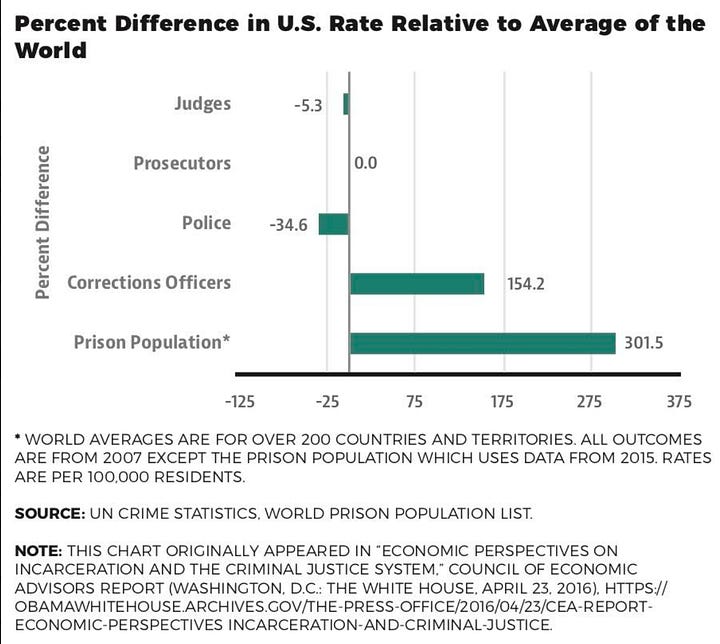

Overall, compared to global averages, the United States has an average number of judges and prosecutors, one-third fewer police officers per capita, 2.5 times as many corrections officers per capita, and four times as many prisoners per capita. (Chart #1).

Most crimes don’t get solved– police solve just over half of all homicides, one quarter of robberies, and one in nine burglaries, and just under a third of rapes. And that’s for reported crimes, of course. And yeah, if it needed to be said, our crime stats aren’t good– we’re in the top one-third globally both for overall crime and murder. And again, the countries doing worse than us are mostly (or all, in the case of homicide) a lot less developed.

And just to be extra clear, yes, police do prevent crimes in addition to solving ones that already happened. The effect isn’t tremendous– hiring more police, by itself, wouldn’t completely solve our crime problem. That said, police prevent more than enough crimes to justify the cost of having more of them. And that of course is only when you view crime through a financial lens, without considering it's less tangible moral, social and psychological costs.

Cesare Beccaria is rolling over in his grave right now, and one of the central questions in criminal justice is, What the hell? Why are we doing the opposite of what everyone knows works best?

I didn’t get a great answer to this when I was studying criminal justice– mostly, my professors blamed widespread “tough on crime” attitudes, which could explain strict sentencing but doesn’t explain why we aren’t putting more effort into catching criminals and punishing them quickly– surely “tough on crime” would mean doing more of all three?

One might argue that lengthening sentences is the simplest and easiest of the three to accomplish, which is true– but it’s also the least effective, and not necessarily the cheapest either.

And that gets to what I have come to believe is the real explanation: money. As you’ll see, the US federal system, and the way in which it divides the responsibility for various parts of the justice system between different levels of government, creates perverse financial incentives to allocate resources in a way that prioritizes the prison system over both law enforcement and the courts.

How the US Federal System Causes Us to Get This Backwards

As mentioned earlier, the US doesn’t have a particularly large number of police. In these sorts of discussions, Europe is usually the comparison people bring up because it’s culturally and developmentally similar to the US, and also because comparing us to a lot of countries is better than cherry-picking just one.

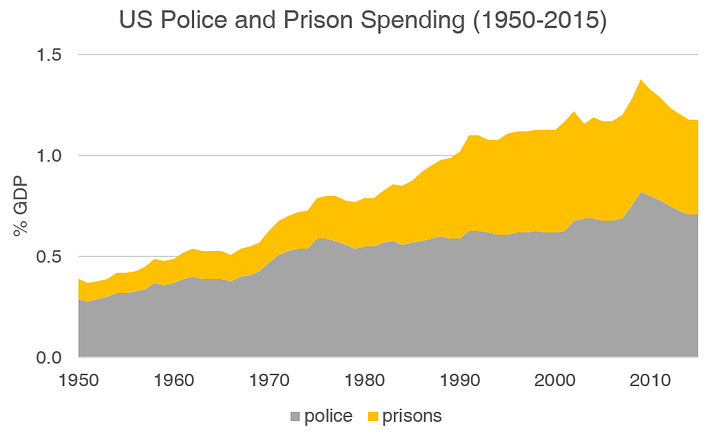

Since the US has more crime– and more violent crime in particular (not always more property crime), you’d think we’d spend more on our justice system. But actually, not particularly– the US spends about 1.25% of GDP on police and prisons combined, compared to 1.2% in the EU. The breakdown between the two is quite different though– the US spends .75% on police vs .5% on prisons, while the EU spends 1% on police vs .2% on prisons. (Chart #2).

Yes, we have a higher total and per capita GDP so we spend more overall, but that just means cops and guards get paid more, since Americans in general get paid more– we still don’t get more of them unless we spend a greater portion of our GDP on them.

So, why the difference? The US has a much more decentralized system of government than most countries in the world, and European countries in particular. Most importantly, those two components– police and prisons– are the responsibilities of different levels of government.

Most trials in the United States take place under state law, and most prisoners are held in state prisons. These are run and paid for by the state, and they hold felons– people who got sentenced to over a year of incarceration.

Misdemeanor convicts who got sentenced to under a year are held in jail, but they usually get probation instead. Defendants awaiting trial are also held in jail, unless they get out on bail, which they usually do. Jails are funded by counties, generally.

Police departments are operated and paid for by the local government, with a minority of funding– typically 10-15%– coming from state and federal grants. Sheriff's departments are funded and operated by county governments, again with a little help from state and federal grants.

You with me so far? Law enforcement is funded locally, prison is funded at the state level.

So, police funded locally, prison funded by the state. That leaves the third leg of the justice system– the courts. Courts are run and funded by local and county governments, again with a tiny bit of state and federal aid. Exactly how this works in terms of judges and district attorneys being elected vs appointed varies, but they’re local entities.

The courts decide, within certain guidelines, how strict punishments are. These guidelines can be pretty broad– for instance, first-degree robbery in California gets you three to nine years. Of course there’s leeway about which charge to file too– downgrade that to second-degree, and it’s two to five. That leaves the courts a lot of discretion– someone who committed first-degree robbery could effectively get anywhere from two to nine years, even before you talk about plea bargaining down to an even lower charge.

Now, look at this from the perspective of a local (or county) government. Law enforcement is a better solution, but it costs your money. Prison is an inferior solution, but it costs other people’s money.

And that right there is the central point of this article– the way the US federal system divides up responsibilities between different levels of government produces strong incentives to try and pass the buck by spending some other government’s money, even if your government is the one with the best tools for fighting crime.

This your money vs their money distinction causes local and county governments to habitually under-spend on law enforcement and try to make up for it by overcharging and over-sentencing defendants. They know this doesn’t work very well, but for them it’s the choice between an optimal solution you have to pay for, and a sub-optimal one that other people have to pay for.

Now, the city council and the voters can’t directly dictate charges and sentences in criminal cases, it’s true. However, they have ways of influencing outcomes. The obvious ones are that DAs and judges are local officials– usually elected, sometimes appointed. District attorneys almost always run as being as tough as possible. Judges are supposed to be impartial, but they usually err on the side of being tough on crime as well. And of course, when up for re-election, they’ll face much greater electoral penalties for having let one dangerous criminal go too early– who then killed, raped or kidnapped someone– than for a lot of little incidences of overcharging defendants.

Local governments have more subtle ways of tilting the odds too. Grand jurors are mostly retirees, who tilt strongly conservative, and the remainder are mostly unemployed or government employees. That’s not an accident– grand jurors are volunteers, and the time commitment is such that retirees are the main people who ca do it. Governments certainly could make it a smaller time commitment and try to get more people to do it, or even make it a compulsory draft like trial juries, but they don’t.

Speaking of local juries, there are ways to tilt their composition, and I recently witnessed one. I was on call for jury duty in Los Angeles a couple months ago– I didn’t get called in, but I did note the pay– $15 a day only starting on the second day, plus 34 cents a mile, one way only. For comparison, California’s minimum wage is $14 an hour, going up to $15.50 next year, and in Los Angeles it’s $16.04 with inflation-based increases going forward. The IRS values driving at 62.5 cents a mile– both directions, of course.

These slave labor wages are a bigger deal for some people than others. Obviously the wealthy can more easily afford to skip some work, but the bigger issue may be that salaried employees don’t directly lose money by missing work the way hourly employees do. Of course, retirees lose nothing at all, not even career opportunities or visibility at their job. The near-zero pay for jury duty gives some people a greater incentive than others to try to dodge jury duty.

And then of course there are the public defenders– they’re also funded mostly locally. Some states provide more funding aid than others for them– California is one of the worst in that regard. They’re perpetually under-funded, generally to the bare minimum that state and federal law requires. Many defendants don’t even receive the bare minimum degree of effective counsel that the constitution requires.

And why would they? The cost is significant– in Los Angeles County, for instance, it comes to $354 million for the public defender and alternate public defender’s office2 combined. That’s about 1% of the county’s budget, so not huge, but still significant. More importantly though, the public defenders’ job is to get defendants shorter sentences, or occasionally even get them acquitted– the exact opposite of what local and county governments want to do! If public defenders were free, the government would still have a strong incentive to weaken them.

In short, local and county governments have every incentive to under-police and over-sentence, and they do just that. So we’ve answered the question I posed at the beginning of this article– why are we following this strategy that we know is ineffective?

Of course, mass incarceration only began in the 70’s, so the next question is, why didn’t we start following this dumb strategy sooner? What changed to make us start favoring a demonstrably bad solution to crime?

Why Mass Incarceration Happened When It Did

As I’ve mentioned, the common explanation of blaming “tough on crime” attitudes for mass incarceration fails to explain why those same attitudes haven’t also lead us to invest more in policing. Another problem with that explanation involves timing.

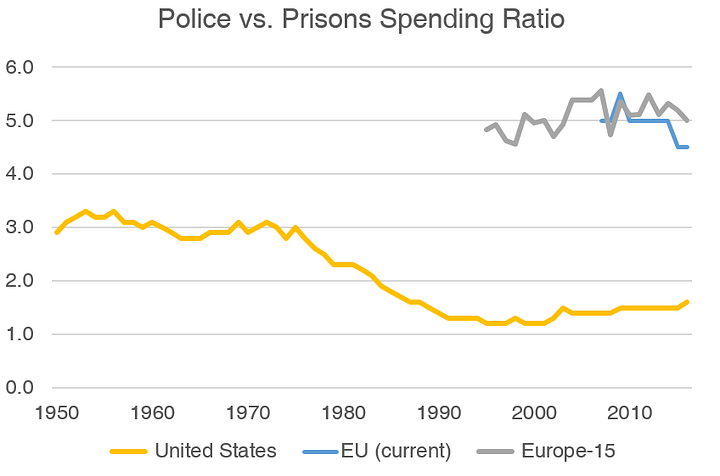

Our trend towards mass incarceration began in the early 1970’s. That’s when the prison population went up, when prison spending went up, and when the ratio of police to prison spending started to drop. It had been about three; it dropped to just over one around 2000, and has since recovered to a bit less than one and a half.

Because the harm inflicted by crime is mostly local, local and county governments have always had good incentives to take the most effective approach to fighting crime. Starting in the 1970’s, however, the cost-saving incentive began to overpower the incentive towards effectiveness. (Chart #3).

The 1980’s are seen as a sort of conservative revolution– the trend towards mass incarceration continued then, and while it arguably accelerated a bit, the growth in law enforcement spending slowed down at the same time. It continued throughout the 90’s as well, before slowing down beginning towards the end of that decade and then reversing modestly beginning towards the end of the 2000’s.

Overall, there just isn’t a clear relationship between the growth of mass incarceration and overall political attitudes or the relative fortunes of the two major parties. It started under Nixon, and continued until about the start of Obama’s tenure. Under Obama it began a gentle decline, which actually accelerated a bit under Trump. Control of congress, governor’s mansions and state legislatures also switched hands throughout this time.

There is, however, a clear relationship between mass incarceration and the cost of policing.

You’re probably aware that police these days tend to make a lot of money, at least in most of the country. To really understand how much they make though, we need to look at total compensation.

The base salary for police officers tends to be close to average in most states, but it varies dramatically across different states and municipalities. Interestingly, there’s a very consistent that police get paid more in blue states than in red states– you may have seen that one map showing that police earn more than teachers in blue states, and less than teachers in red states.

Most cops rack up a ton of overtime though. Typically this works the same for them as for anyone else– they get time and a half for working over 40 hours a week, or over 8 hours per shift, and sometimes also for night shifts. And they often do all three, with four twelve-hour shifts a week being standard, and officers alternating day and night shifts every few weeks or months. Most officers work hundreds of hours of overtime a year, and some get over a thousand. This can often more than double their base salary, and it’s not at all uncommon for the lowest-ranking patrol officers to earn over 150k a year.

The big hidden cost, however, is in their pensions, which are typically more generous than the already-expensive defined benefit programs that most government workers receive, and which the private sector has mostly moved away from since IRA’s and 401k’s were rolled out in the 70s.

Police pensions are typically based on a percentage of the pay an officer earned when they retired– either their final salary, or more commonly their average earnings over the last one to several years. Crucially, it’s often based on total pay including overtime, rather than just base salary.

Take the Los Angeles Fire and Police Pension plan, for instance. Officers pay eight or nine percent of their earnings into it. Here’s how it works:

Your Final Average Salary equals the average monthly pay you received in the last 12 consecutive months prior to retirement. Upon, retirement, you may also have the option to designate which consecutive 12-month period you want to use to calculate your Final Average Salary….You receive 50% of your Final Average Salary at 20 years of service, plus 3% for each additional year of service; except in the 30th year you receive 4%. The maximum percentage payable is 90% of your Final Average Salary at 33 or more years of service.

Got that? It’s based on your total earnings, including overtime over a one-year period– 50% of that at 20 years of service, up to 90% at 33 years.

It’s easy to see how officers game this system– for either their last year before retirement or a one-year period not long before that, they overwork themselves and rack up as much overtime as the department will let them. An officer can easily retire at 40 years of age and earn a pension of over sixty thousand dollars a year. If they wait until their early fifties to retire, it’s not hard to draw a six-figure pension– for the rest of their lives.

It’s no wonder that most of the former government employees drawing six-figure pensions are ex-cops.

Okay, but back to our question– why the early 70’s? It has to do with police unions.

Policing didn’t used to pay this well. Back in the 50’s, police officers earned about as much as the average full-time employed man. In fact, from the late 19th to early 20th centuries police officers drew below-average pay and labored under poor working conditions, leading to many early attempts at unionization, which mostly failed.

The reason they failed is because there were a lot of anti-union laws back then, particularly regarding public-sector unions. That started to change in the 30’s under the New Deal, though more so for the private sector. Once private sector employees were allowed to unionize though, it created more pressure to allow the same for government employees, both out of fairness and because government salaries need to be at least somewhat competitive to attract good workers.

Collective bargaining by public-sector employees was legalized in various states mostly between the 30’s and 60’s. The federal government legalized most forms of collective bargaining by municipal employees in 1958, and federal employees in 1962.

This didn’t lead to overnight change, because it still took a while for police unions to organize and really start to take full advantage of their new collective bargaining power. Local police unions started negotiating higher pay throughout the 1960’s, but the trend really took off when they began coordinating with each other.

In 1976, former officer Ron DeLord organized all of the local police unions in Texas into the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, combining their bargaining power statewide. He then began a career as a political consultant, helping police unions around the country maximize their bargaining power and then utilize it to maximum effect. In 1997 he published a book titled Police Association Power, Politics, and Confrontation: A Guide for the Successful Police Labor Leader, sharing his whole playbook with every police union leader in the country.

So, you can see the timeline here– police unions form in the 60’s or very late 50’s and begin tentatively negotiating higher salaries, and in the early 70’s you see the first hints of mass incarceration. Then from the mid 70’s onward, unions really begin flexing their muscles and police start getting paid upper middle-class wages. At that point, local and county governments start shifting costs to the prison system, and mass incarceration takes off.

In Chart #4, you can see how the rise in prison spending was preceded by a rise in police spending. Cities and counties initially absorbed the cost of paying police and deputies more, but as salaries began to weigh on their budget, they curbed the growth in law enforcement costs by shifting to a strategy of mass incarceration.

It has always been the case that cities pay for police and states pay for prisons, and so cities have always had this incentive to under-spend on policing and shove criminal justice costs off on state governments by over-sentencing. For a long time they resisted this incentive because everyone knew that this is actually a pretty shitty way to fight crime.

What changed was that the police got a lot more expensive, to the point where cities could no longer afford to ignore the perverse incentives at play. In economic terms, they began switching from their favored choice to an inferior good– a cheaper but less desirable alternative that they wouldn’t buy (or buy as much of) if the thing they really wanted– more police– was affordable. And in this case the inferior good– imprisonment– was mostly free, at least if you ignore the indirect costs arising from higher crime rates.

This leads us to a counterintuitive observation: police unions are bad for society in part because policing is good, and they make policing overly expensive. This may be hard to swallow if you view the police in moral terms, but it’s exactly how the science of economics works. Housing is good for society, and NIMBY’s are bad because they conspire to make it more expensive. And now that people have realized that, America is pushing back against them. The same fundamental relationship exists here– it’s best for society if a vital necessity is cheaper.

Over that same time period, prison guard unions got power powerful, similar to police unions, compounding the financial problems for states.

Of course states have made their own efforts to minimize the costs being pushed upon them by local governments– by getting more generous with parole, reducing maximum sentences or providing less flexible sentencing guidelines or, more recently, privatizing prisons. That last one has a lot of problems. Not only do privatized prisons generally suck, but the companies that run them can hire lobbyists like anyone else– and they really, really would like us to put more people in prison.

Privatized prison corporations don’t want what’s best for America– they can’t, really, they have an obligation to their shareholders to try to make as much money as they can.

So now we have a line of cause and effect from police unions, to a shift from policing towards mass incarceration, to a self-reinforcing system in which privatized prisons encourage mass incarceration, which causes– or at least fails to solve– crime, which delivers more inmates to privatized prisons and increases the overall financial pressure to shift spending from police, to state-run prisons, to privatized prisons, which try to get the government to imprison more people in whatever way does the least to reduce crime, and so on.

It’s also worth noting that, as costs in the justice system rose, state governments likely found it easier to raise taxes than local governments. Not only do state governments have broader taxation powers, local governments are likely more concerned about tax flight. If you want to reduce your tax burden, it’s a lot easier to move just outside the city limits than to move to a different state, so municipal governments have to be more cautious about when, how, and how much they raise taxes.

The upshot of all this is that municipal (and often county) governments have been financially squeezed from both ends– their costs have gone up, and their ability to raise revenue has been more constrained than for state and federal governments. The rise of mass incarceration has resulted largely from efforts by local and county governments to offload the costs of the criminal justice system onto state governments.

How To (Make the Government Want to) Fix the American Justice System

It should be clear by this point that the fundamental problem with the American justice system stems from the way in which responsibilities are divided. Specifically, the issue is not not the responsibilities for managing, but the responsibilities for funding different elements of the system. Because cities and counties pay for policing but not (mostly) incarceration, they under-police and use their influence over local courts to over-sentence.

If states had total control over the courts, we’d likely have the opposite problem: under-sentencing with the intent to pressure cities and counties into compensating by over-spending on law enforcement. The only true solution lies in cost-sharing between state and local/county governments.

State governments should provide matching funds to local police and county sheriffs department budgets, in order to make law enforcement cheaper for those governments. At the same time, state governments should charge some percentage of the cost of incarcerating offenders to the local or county jurisdiction which sentenced those offenders.

In theory you’d want to split all of these costs 50/50. In practice, because this is likely to require changes in the tax system to fund major changes in expenditures, cost-sharing policies would likely need to be more modest, at least to begin with.

To begin with, states could provide one dollar of matching funds for every two dollars that local and county governments spend on their police and sheriff’s departments. This should be capped at some per-capita number to keep expenses within some predictable limit

As for correctional costs, states could charge one-third of the cost of incarceration back to the county which sentenced the inmate in question. At the same time, states should provide matching funs to county jails– again, perhaps one dollar for every two spent by the county– to reduce to incentive to sentence low-level offenders to prison instead of jail time.

Note that this means that county governments will need to substantially grow their tax revenues. This will likely take a few years to fully implement.

In addition to sharing the costs of law enforcement and correctional facilities, states should also share more of the costs of the court system. Public defender’s offices, perpetually under-funded, should receive even more matching funds from the state than police and sheriff’s departments, or even be entirely state-funded.

Additionally, states should enact more stringent requirements for the capabilities and capacity of public defender’s offices. Defendants should receive adequate counsel, both as a matter of justice and to counteract the local tendency towards over-sentencing.

It is also worth considering an expansion of court capacities. So far we’ve mostly discussed the tradeoff between certainty and severity of punishment. But remember that according to Cesare Beccaria’s theory– which has ben borne out by modern experimentation– swiftness of punishment also has a greater impact than severity. In principle, expanding court capacity in order to move cases along more swiftly should also help substantially in deterring crime.

Building excess capacity would likely mean that courts would have some “slack time” in their schedules when cases come in slowly. However, if this buys us more deterrence, and also means that the most dangerous criminals go to prison faster and spend less time out on bail, it would be worth the cost.

Finally, we should look at ways to get more value for money from law enforcement. This part is going to be difficult, for a few reasons. First, police unions are powerful and deeply entrenched. Second, in spite of how much police get paid, they do actually seem to be worth it– they reduce crime enough to justify the cost. Third, from a moral standpoint, police probably should have the same right to collective bargaining as any other government workers. There is, however, a separate question of whether government workers should have the same collective bargaining rights as private sector workers, given that they exercise effective monopoly powers over their professions.

Overall, I’m pretty skeptical about the potential to cut costs by paying police less, although I do see some opportunity to both curb costs and make the cost of policing more predictable.

The focus for cost reduction should be not on base salaries– which are usually fairly reasonable– but on overtime pay and pensions, which, as we’ve seen, add up quickly in a synergistic manner. City and county governments should put limits on how much overtime law enforcement officers can accrue, and on how much overtime pay can count towards an officer’s pension plan.

State governments can help here– state matching funds could not apply to pension plans, or have strict limits on how much overtime pay can be eligible for matching funds. That would provide an impetus for more of officer pay to come in the form of base salary– the “sticker price,” as it were, making law enforcement expenses both predictable and transparent.

Police commissioners and county supervisors should have more leeway to fire bad officers– either those who commit abuses, or those who simply aren’t doing their jobs. Again, state governments could essentially force this change by making it a condition for receiving matching funds.

Finally, law enforcement could deliver more value for money by improving officer productivity rather than reducing officer compensation. Traffic enforcement, except in cases of extremely dangerous driving, could consist of mailing drivers a ticket without pulling them over. Mental health and wellness checks, could be conducted by health specialists, as long as there’s no reason to expect danger. Officers could receive more ongoing training and spend more time on high-value investigative tasks.

With a modest investment in lab capacity, the justice system could do a better job of actually using all the forensic evidence that officers and crime scene investigators collect, including clearing the rape kit backlog, which has been a known issue for many years. These sorts of investment would get us more crime-fighting and crime-reduction per officer, and they become a better investment the more officers get paid.

Conclusion

The incentives in the American criminal justice system push it towards having fewer police and far more prisoners than would be optimal for society. Local and county governments currently get to choose between a good solution paid for by themselves, or a bad solution paid for by the state, and they tend to choose to save their money. The result of this incentive problem is high crime and mass incarceration, with all of the social, financial and public safety costs that those things entail.

The solution is to align the incentives– for the costs of both law enforcement and the correctional system to be shared by society as a whole. If we want governments to pick the best solution to society’s problems, we need to stop letting them finance the worst solution with other people’s money.

John Fawkes is a prolific writer who covers such diverse topics as fitness, self-improvement, economics and housing policy, both on his Substack blog and on Twitter at @johnfawkes. He has a degree in criminal justice; this article is the first time he’s ever used it.

Fascinating! I think this is the first time I've heard of solutions to crime and policing that don't villianize any group or rely on partisan/ideological assumptions. I haven't been this impressed with a wonky policy solution since I learned about Georgism.

As far as how to make it go down politically, anything that would increase numbers of police won't be accepted by wide swaths of liberal voters unless it's paired with some of the other solutions you mention like making it easier to fire bad cops and/or replacing armed police with automation or health care workers in some situations. I wonder if police unions would accept that trade: more membership but decreased power to protect all members and slightly decreased responsibility of police. It'd be hard to frame the reforms in a way that makes it acceptable to both sides of this culture war: admitting that police are harmful sometimes and also helpful sometimes is more nuance than most can handle.

This is incredibly impressive, especially for a guy who isn't focused on this topic. This is an original perspective I've never come across before, and I find it convincing. You lay out your case very well with just the right amount of supporting details and arguments. My compliments to DO for bringing in an outside voice that might differ from him on some opinions.

Some scattered thoughts:

Aside from incapacitating the most dangerous criminals sooner, funding courts would also shorten the time the innocent spend in trial and pre-trial detention. I wanted to add that because I think funding courts is a no-brainer that everyone can get behind for one reason or another.

On crime reporting and clearance: I've done a very deep dive into the FBI's homicide data, downloading and analyzing all 800,000+ murders in their database going all the way back to 1976. You may be interested to know that murder reporting is probably lower than you think, but clearance rates may be higher.

With respect to murder reporting, I compared county level totals, as reported by police agencies, to the numbers of homicide victims reported by coroners to the CDC, and found that they differ by as much as 30% in the some states. Putting that together with some other evidence that would be a little too much to go into here, I estimate that the murder rate in the US is probably about 15-20% higher than usually usually stated, and that the undercounting ranges from possibly 10% in the best states to probably 40% in the worst (Mississippi is the worst in case you're curious).

On clearance, the good news is homicide clearance is probably much higher than found in the data. Professional audits have found examples of individual police department underreporting clearance by as much as 30%. The issue seems to be a simple lack of care for the data that they are reporting to the FBI, and a consequent lack of training and review of that data.

The bad news is the national clearance rate appears to be steadily dropping since 1976, from about 75% to 65%. Whether that's real or an effect of sloppier data standards I can't tell.

But more negatively, clearance rates by demographics are diverging. In the late 70s, the clearance rate for any combination of young adult, male or Black victims was actually higher than was the rate for any combination of older adult, female and non-Black. But since then the clearance rate for the latter 3 descriptors has risen while the clearance rate of the former has fallen drastically.

So for example in the late 70s the murder of a young, Black male had a 80% chance of being reported as cleared, while the murder of an older, not Black female had a 70% chance. Fast forward to the 2010s and the chance that the young Black male's murderer is arrested has fallen 25% to just 55% while the older, not Black female's chance of clearance has risen 20% to 90%!

One last thing: I feel something was left out of the international comparisons on prison populations. Severity of sentence should be compared directly. Comparing the sizes of the prison populations ignores the possibility that more crimes are happening here than in Europe. I've seen it argued that prison sentences for murder in many European countries are actually longer and gun possession charges are much, much longer and more aggressively prosecuted than in the US. Therefore our larger prison population is due to more crime, and not lighter sentencing. I wish I could easily find a source that rigorously compared average sentencing by crime, but I haven't found one yet.

Also I think we are more culturally similar to Lain America than we are to Europe, but most people don't seem to agree with me, lol.