Oakland’s not gotten great press coverage lately. First, a food-poisoned TikTok foodie went viral saying that city’s homelessness crisis indicated Oakland was no place for tourists. Then, In-N-Out Burger went viral after announcing the closure of its first store in history near the Oakland airport, citing employee theft and robbery as the cause. Now, Kaiser Permanente, one of Oakland’s largest employers, has advised its employees not to dwell in downtown for risk of being robbed. As of writing this, a video is going viral of Oakland In-N-Out patrons watching a security guard getting robbed at gunpoint.

The entire city of Oakland gets a bad reputation for its most troubled neighborhoods. I was contacted for a news interview about my guerrilla bench program while in safe North Oakland, and NBC made me traverse back over the Berkeley city limits because reporters feared being robbed in Oakland. Sometimes reporters contribute unfairly in this universalization of Oakland’s western and eastern neighborhood-limited problems. When reporting on crime, San Francisco-based media always specifies which frequent neighborhoods they occur in, such as Tenderloin or Bayview, yet uses “Oakland” as this singular place for murder and poverty.

But it’s not as though Oakland’s reputation is wholly ginned up out of nowhere. Oakland’s 9-1-1 hotline is so overloaded on some days that operators won’t answer, which is terrifying. Just 13 days into 2024, Oakland’s homicide count had already reached six people killed. Oakland’s police department has been ineffective for so many years that, when I lived in East Oakland a decade ago, my family wouldn’t bother contacting the police except to report homicides.

There’s four problems gripping Oakland. First is homicide, which is usually is an act of domestic violence or young male adults fighting each other with guns. Shootings are mostly among known acquaintances, but shooters frequently hit unrelated people or nearly miss them in the process. The second is organized criminal groups, whose participants are school dropouts, poor kids in and out of juvenile hall and jail, and to some extent, organized theft rings. The third is Oakland’s reckless drivers speeding and killing people at increasing regularity. The fourth isn’t a crime, but it is what many notice about Oakland, which is people without housing living in shanty towns and RVs.

Here’s what TikTok star Keith Lee said about Oakland during his visit:

I truly don’t believe the Bay is a place for tourists right now . . . The people in the Bay are just focused on surviving. That’s the business owners, the locals. The amount of tent structures and burnt-up cars we saw people living in was shocking, to say the least. . . I wish the city would step in. I don’t know if they have, I don’t know if they’ve been trying, but as an outsider looking in, it doesn’t seem there’s much city interference.

We had a million think pieces come out about what this signifies. It shouldn’t be news. This is what the vast majority of people who come to Oakland that are not from California think. But what annoys me are locals who in rebuking Lee’s assessment, scoff at his shock at the homeless crisis. Here’s a snippet from SFist.

So, to recap, we know Lee ate two burgers in San Francisco, a fried fish sandwich and some tacos in Oakland, had a shellfish allergy reaction, saw some tents, and gave the Bay Area a blanket, irresponsibly general, middling review that is frankly kind of meaningless.

I get annoyed when Bay Area people, who usually consider themselves progressive, get annoyed at newcomers being shocked by the homelessness crisis. If you’re not from California, it is pretty shocking. Keith Lee was raised in Detroit, which has seen its homeless population drop by 16,000 since 2007 and has 200 unsheltered homeless persons compared to 3,330 in Oakland. Half (48%) of all unsheltered homeless people in the entire United States — the people you see living in tent encampments and unsanctioned RV communities — live in California, despite the state representing just 12% of the nation’s population.

That’s because California cities are full of politicians and activists who are uneducated, refuse to look at unanimous, empirical solutions to homelessness (supportive housing, higher housing supply / higher vacancy rates, lower rents), and only know how to criminalize homelessness and / or not build homes. Idiots in California sit there, flabbergasted as to why the state with the lowest housing availability in the nation has tents everywhere.

But if I were to rank all cities in the state based on how responsible they are for this crisis, Oakland would be at the bottom. Oakland’s homelessness crisis is almost entirely the fault of San Francisco and Silicon Valley, and there’s little Oakland can do about it by itself.

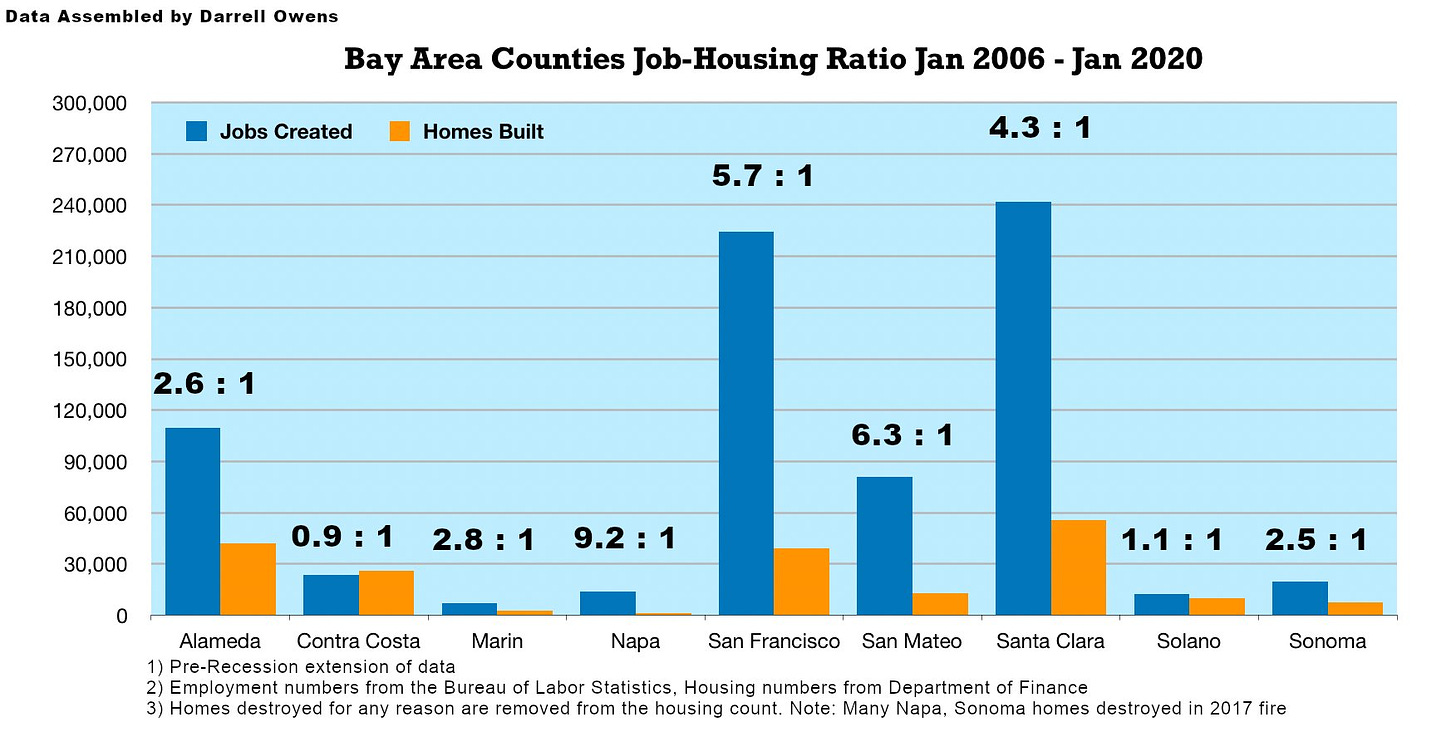

In 1990, Oakland had only around 734 homeless people while S.F. had eight times as many unhoused. (Recall that S.F. is a deeply unserious city on housing policy that cannot solve the same crisis 40 years in a row). Starting in the 1990s, San Francisco and Silicon Valley pursued an aggressive office development program, which attracted far more employees to the region than homes available. Since 2006, that ratio in San Francisco has been 6 new workers for every 1 new home built. Since the 1970s, SF and the Peninsula banned new housing in most of their neighborhoods, depending instead on Oakland and the East Bay to house their commuters.

San Francisco takes 3 years longer than Oakland to approve new housing, because San Francisco is run by anti-housing politicians and organizations who pocket the tax gains from offices downtown, but don’t want new residents changing the city and straining services. Home prices in Oakland skyrocketed for 30 years, starting in North Oakland and spreading to every neighborhood east and west. However, housing couldn’t be built fast enough because financing dried up during and after the Recession. Where housing was financially viable in high land value areas in the West Bay, where many people work and would like to live, zoning and permitting laws make it functionally illegal to build. Oakland’s vacancy rate declined as the city’s population grew nearly three times the rate it built housing between 2010 and 2020. Neighborhoods are severely overcrowded, especially in the garages turned faux-bedrooms of West and East Oakland.

By 2009, Oakland’s homeless population grows to 1,000, then to 2,700 by 2017. Meanwhile, S.F. and the Peninsula swim in massive municipal budgets from all their commuter-based tax revenue, without the fiscal externality of having to house their workers and pay for public services. That liability is Oakland’s job, but Oakland is collecting only the crumbs of the West Bay’s job creation via property taxes from new home buyers. Under Proposition 13, property taxes is less reliable for Oakland due to longtime owners paying low property taxes, and makes the city’s budget dependent on gentrification. Wealthier workers buy houses from longtimers, which under Prop 13 makes property taxes increase to current market assessments.

Whatever property taxes Oakland collects goes to swelling infrastructure, public employee pensions, schools and new public service demand that comes with a growing population. Thus Oakland, a city half the size of San Francisco, has a budget only a quarter of S.F.’s size and doesn’t have the funds to build housing for its ballooning homeless population, let alone its housed population. This strains public services even more because the ballooning homeless population requires dedicating public funds for nonprofits to provide services, along with trash clean up by public works, and police / fire response for accidents at encampments.

Though Oakland had a few tents in parks for many decades, the massive encampments that sprawl around Oakland’s freeways and BART tracks has its origins in the Occupy movement. Oaklanders lost their homes and jobs in the Great Recession and camped out in protest. But it didn’t become the full-blown sprawling shanty towns until 2017, after San Francisco voters passed Proposition Q, which swept homeless people from downtown San Francisco. SFPD and the DPW would actually trash homeless people’s tents, give them BART tickets and direct them to Oakland.

Oakland has nowhere as much money to enforce against encampments as S.F. and a lot more vacant industrial land, so after Prop Q passes, encampments and RV communities spring up around West Oakland, under Highway 24, around the San Antonio district and Coliseum area. Many of these RV encampments are also refugees from sweeps by Caltrans, Berkeley, San Leandro, Alameda and Albany, where their larger budgets per-capita enable them to remove homeless people much more easily than Oakland. Within two years after Proposition Q passes, Oakland's homeless population nearly doubles to over 4,000.

Mass homelessness is Oakland’s problem, but it’s not really Oakland’s fault and Oakland cannot solve it alone. Even if Oakland abandoned all law enforcement and dedicated the entirety of its $330 million bi-annual police budget to only building subsidized housing, we’re looking at 175 to 800 subsidized homes a year, depending on matching subsidies. Low income housing in Oakland costs $1 million dollars per home, now. This is why we need a Bay Area Regional Affordable Housing Fund, so that Oakland can collect its fair share in taxes from job-heavy, wealthy jurisdictions that depend on Oakland.

Homelessness is not a crime, hence why this is separate from the discussion of actual crimes in Oakland I’ll discuss on Monday. Unsheltered homeless and the public health crisis disproportionately hits Black and migrant populations, poor people, seniors without retirement pensions, and people with mental and physical disabilities. It’s hard to witness homelessness but it’s even harder to experience it. The research is clear, even though the Bay Area ignores it, that we have but one solution to homelessness and it’s housing.

As far as crime goes, it is far-deadlier to be a homeless person than it is to be near homeless people. Homeless people are disproportionately the victims of crime, not the perpetrators. Oakland, for all its problems, does housing policy better than all of its neighbors — but it can’t solve the regional housing crisis alone. Put the blame for Oakland’s encampments on who caused them: Oakland’s “nicer” neighbors who evicted them, not Oakland who kept them.

Ask anyone who actually works with unhoused people to get them into housing: there are almost no shelter beds and almost no permanent housing opportunities in California. If a person in a tent on the sidewalk says they'd like to move inside, the paperwork takes a couple of months, getting a housing voucher takes a couple of months, and then finding a place that will rent to them takes a couple of months. Meanwhile the person is still on the street with no restroom, no shower, no safe place to keep their identification and other paperwork, and getting limited sleep. Their encampment may be "cleaned up" by the city and then they've lost all their stuff, and the case manager has to go search for them and probably start over. A recent study (by McKinsey) found that while 207 unhoused people in Los Angeles become housed daily, 227 lose their housing and join the ranks of the unhoused each day. The meager "resources" (money, vouchers, shelter beds, and dedicated PSH apartments) that are available are mostly reserved for people who are chronically homeless. To its credit, Oakland is trying to be compassionate.

Interesting and comprehensive analysis with at least one serious omission.

Affordable housing has never meant new housing. This combination of 'new' and 'affordable' applied to housing is impossible, as your analysis proves with new homes costing $1M to build. If you do the math and the population numbers, it is clearly nonsense. Taxpayers cannot do it.

Housing has always been built with private investment (there, I said it) based on the profit motive (yes, that's what makes everything happen) and operating under 'reasonable' government regulations. Affordable housing has always been USED housing. Hand me down, like clothes or cars.

But with no new housing being built, the supply of old housing dries up under the pressure of demand. Result: homelessness.

Low rents and home prices have always occurred after periods of overbuilding. To restore affordability, promote and manage reasonable overbuilding.

Solutions: Strip away all but the most important regulations. Lots of obsolete zoning and building rules. Never reviewed and cleaned out. The State is starting but just scratching the surface.

Then the engine of homebuilding will restart.

Finally, there is an enormous contradiction between our market economy in housing and the emotional claims of residents to their given geographic place on earth. Land and homes and apartments are for sale to the highest bidder, a system that triggers more supply to be built and allows us to have mobility that most of the world envies. However, we also have real feelings for places where we feel we belong, our family belongs, and our 'people' (dangerous!) belong. (Chinatown? Little Italy?) 'Home' is not just a house or an apartment and 'Neighborhood' is not just where I currently can afford to live. But cities and neighborhoods change and our market economy would respond, if we let it. But we demand no change, scream about 'gentrification' and listen to claims that the unhoused are 'our people' and deserve to live in our expensive city because a survey run by nonprofits that serve them found that 70% of them said (?) they lived in the County (??) sometime in the last 10 years. Most of us cannot decide to live in the highest priced neighborhoods, camp out there, and demand the other citizens build us a home there.

It's not rocket science. The scale of ignorance about basic economics staggering.

The solutions are there if we abandon the myths and assumptions that no longer apply and pick up the tools again we have always used.