Vacant Housing Lowest In Census History

Using the latest Census report to make it very clear that the housing shortage is indeed real as vacancy conspiracies take foot on social media.

Vacancy discourse is trending once again. So let’s set the record straight: housing vacancies are at all time lows in the United States, and the latest 2022 Quarter 4 report confirms that. The nation faces an inability to find available housing to purchase and rent. This is how corporations and property owners realized considerable profit from the housing crisis, by acquiring rental housing and converting owner housing into rental housing.

Nationwide, the vacancy rate for owner-occupied housing is at 0.8% — the lowest count on record in U.S. Census history since 1956. Vacant homes for sale are posting their highest prices ever, coming off an accelerated incline since the pandemic’s outbreak. The news media is making much out of home prices cooling down but if I were a homeowner, I’d remember that shortages don’t pop. The pandemics’ incline is cooling, but it’s difficult to envision another housing bubble with so little inventory.

Since the early 1980s, we had a steady increase in vacant homes for sale until the subprime mortgage crisis. That availability was primarily powered through single-family sprawl, which skyrocketed in the aughts. Sprawl is easy to build since its materials are cheaper and requires less trained labor than multi-story high density housing. But the subprime crisis left thousands of unfinished new subdivisions sitting vacant, and the general consensus by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the media, financial analysts and the federal government was that the U.S. had overbuilt homes.

Consequently, lenders pulled back on financing new home construction. Real estate investment transitioned from the more complicated process of housing construction which was buoyed by low interest rates to property acquisition. The latter was ripe for capital gains due to the massive amounts of foreclosed homes at auction during the Great Recession.

The Recession also caused a huge drop in labor participation by residential construction workers. While the vacancy increase from mass foreclosures had quickly reversed in under half a decade, it’s taken ten years for the residential labor force to recover to pre-Recession levels. The labor shortage led to insufficient quantities of homes being produced.

Low interest rates fueling a buying spree during the pandemic sent the already low numbers of for sale vacant housing plummeting. This is the reason many Americans who wish to become homeowners will not have that opportunity.

The national rental vacancy rate is at 5.8%, which is not the record lowest point — that’s still the ‘70s — but being close to the ‘70s is a problem. In the 1970s, the nation had undergone a rental housing crisis. Inflation averaged 6.8% then, more than triple the previous decades. The cost of building for developers and maintenance for property owners exceeded the profit they received in rents; mass amounts of rental housing fell into neglect or were destroyed as a result.

For tenants in the ‘70s, rents had far exceeded income and nearly half the country was spending more than 25% of their income on rent. Rent control made a local political resurgence and even Nixon froze rents in the early 1970s via an executive order. Federally subsidized housing starts accounted for 44% of new apartments over four units in size to compensate privately-financed decline in 1978, according to a congressional report.

Today, the problem is growing worse than the 1970s. The Census found that over 40% of tenants in the nation pay more than 30% of their income on rent. Moody Analytics found that the national median rent-to-income ratio has breached 30% of income for the first time. The swell in pandemic-era demand for better housing and low availability of owner-occupied homes prevented whole generations from acquiring homeownership, and made renting even more crowded.

Recall in my old piece that people of all ages need rental housing constantly (something vacancy discourse fails to grasp) and transition in and out of homeownership and renting. Young people leaving home in search of housing, new families seeking more physically accommodating housing options and elderly households desiring to downsize. All these groups are aggressively competing for rental housing alongside families ready to vacate their rentals but are unable to become homeowners.

While the nation is at 1970s lows in homes for rent, breaking the nation down by regions highlights some localized severity. The western states of the country have record low vacant rental housing at 4% — beating out their 1970s lows. California has by far the lowest vacancy rate for housing of any state in the country. The 2022 Q4 report breaks the vacancy rates down as 3.9% for rentals and 0.7% for owned homes. Neighboring states must contend with migrating Californians searching for affordable housing, coupled with their own stagnant housing production and natural population growth.

The northeast’s rental vacancy rate is 3.9%, which quite low but is slightly better than the 1980s record lows of 3.8%. The South has always enjoyed more housing availability than the West and Northeast. However, the South is still at a roughly four decade low in rental vacancies at 7.3%; contrasting considerably with it’s pre-foreclosure crisis high of 12%. The South’s Q4 homeowner vacancy rate is at 0.8%, which hasn’t come close to being that low since 1957.

The final region, the Midwest, follows the national trend of historically low housing for sale at 0.8%. But the rental vacancy in the Midwest is not as bad with a 6.9% vacancy rate. Nowhere as bad as the 1970s where the vacancy rate in the Midwest was significantly lower. The lack of jobs and declining industry of the Midwest has notoriously led its cities to have high amounts of vacant housing. Low income households, most of whom are renters, have been fleeing to the Midwest for years now as a result.

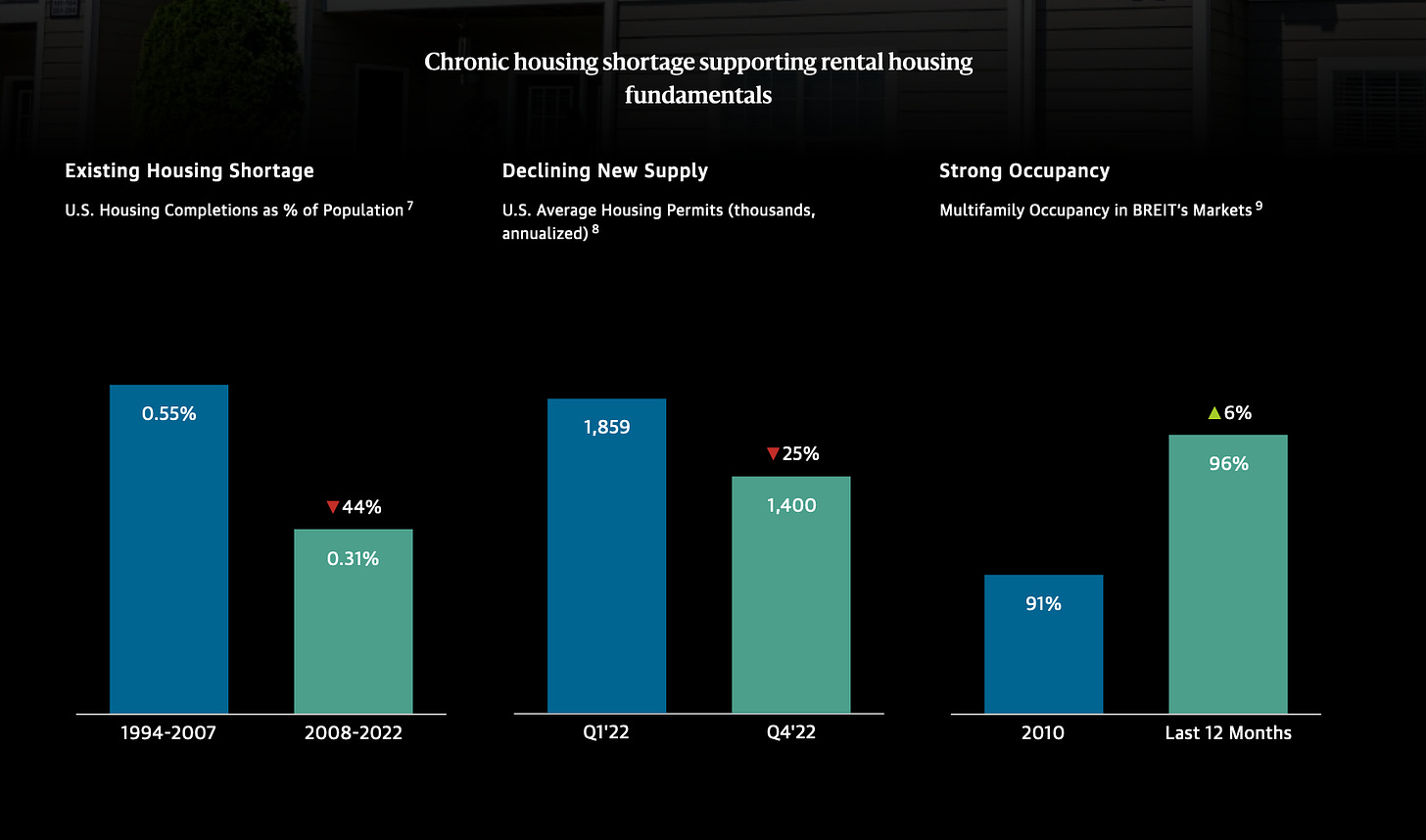

In my breakout article on vacancies I noted that real estate speculators like Blackstone — the most famous landlord in the United States — has been quietly saying in their SEC filings that they profit off the housing shortage. Well they’re not being quiet about it anymore. In their public slide deck they make perfectly clear that their profitability forecast is going on the up and up with home construction down so significantly.

So the primary answer is if you want to beat private equity speculators and corporate buyers then we need to build a lot more housing. Not only should we transform our zoning to allow for more housing, but the federal government should be encouraging and directly financing more investment into developing new housing.

It seems politically impossible today but ideally the president should cap rent growth temporarily until we can built enough homes to compensate. It seems so radical today but Republican president Richard Nixon did it. Also, we need to re-examine ways to encourage housing construction via our tax code. Land taxes come to mind, which by taxing solely land values, would encourage property owners to build housing on underutilized parcels.

So, there isn’t actual evidence to suggest the housing shortage is artificially imposed by corporations not leasing out their properties. An all-time low in empty homes for sale nationwide and all-time lows in empty homes for rent in the western US, alongside universally low vacancy rates throughout the country, suggest we have a severe housing shortage. And corporations are profiting off it.

—

It’s an interesting idea to cap rents. One can expect that it might incentivize increased construction--but only if the entities constructing (developers) are the same as the investors, which is often not the case, which makes it harder to (in a lack-of-coordination scenario) cause developers to create more housing without strong price signals.

In rent controlled situations, sitting in some of those presentations by big investors, the big corporates are usually the ones who can best handle it. Mom and pop landlords can’t control or slash costs (precisely balancing rent/demand) to ensure yields. Goldman touts that they excel in rent controlled cities and it’s a net benefit to them, since they can pick up properties for cheap and “make them productive” by slashing the right costs that don’t damage demand (which is also easier in housing short rent controlled cities).

Anyway, it’s a specific point I’m picking at in an overall commentary/article I agree with here.

It’s a nuanced problem. Free-for-all ridiculous rent increases may drive construction but displace huge numbers of people and create massive social churn with the lag time in construction of new housing (which itself can damage desirability and rents, even if you were entirely heartless and just wanted maximum construction). At the same time, over controlled rents create shortages and benefit those who can dispassionately squeeze the last drops of juice out a property.