Where Did All the Black People in Oakland Go?

I use the Census to examine the intersection of housing policy and affordability in the East Bay Area including how development interacts with Black displacement in Oakland

Try out this Census 2020 Rate of Change map in another tab. I made a tool to contrast the 2020 and 2010 decennial Census to see how communities changed over the last 10 years in California by race and housing. Hover your mouse over a tract to see its data and toggle the drop down menu for the subject you want to see.

The 2010s was really the highlight of gentrification awareness in the Bay Area. Awareness because it dates back to the late 70’s but the 2010s was by far the most visible gentrification we’ve seen in the East Bay. The get-rich-quick software boom really put the “yup” in yuppie and coming out of the worst Recession since the Depression people found themselves in dead-end gig economy jobs or working multiple shifts. The very visible decline of Black residents coinciding with bustling homeless encampments, $1 million homes and glossy residential towers ignited a strong debate over housing policy.

Now there’s been a lot of research coming out on this topic but the Census has provided us with an opportunity to look at some real world correlations. There are some variables to be considered, most prominently that this Census was conducted several months into the worst pandemic in a century thus many conditions of early shelter-in-place have been snapshotted here.

Lastly, employ vigilant skepticism. Question your own conclusions and mine. As a veteran data analyst there is often far more questions than answers.

Oakland

So the very first thing I had to do was to contrast housing development with Black migration patterns in Oakland. Oakland’s fascinating because unlike its neighbors San Francisco and Berkeley, Oakland (excluding Rockridge) never had the 1970s era Malthusian population cap wave. For many years developers outside of the Oakland Hills avoided Oakland, other than small contractors building dingbat apartments here and there. But the 2010s changed things largely because Oakland’s neighbors became unaffordable and mass migration to Oakland ensued. Oakland went from a somewhat stagnant population to becoming the 4th fastest growing city in California, with a 10% increase in population and a severe drop in Black people.

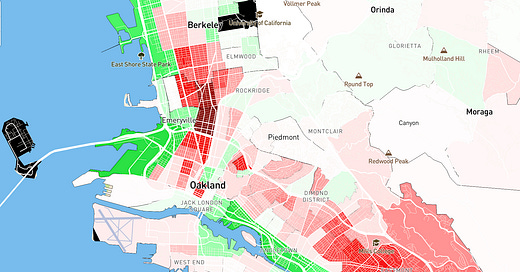

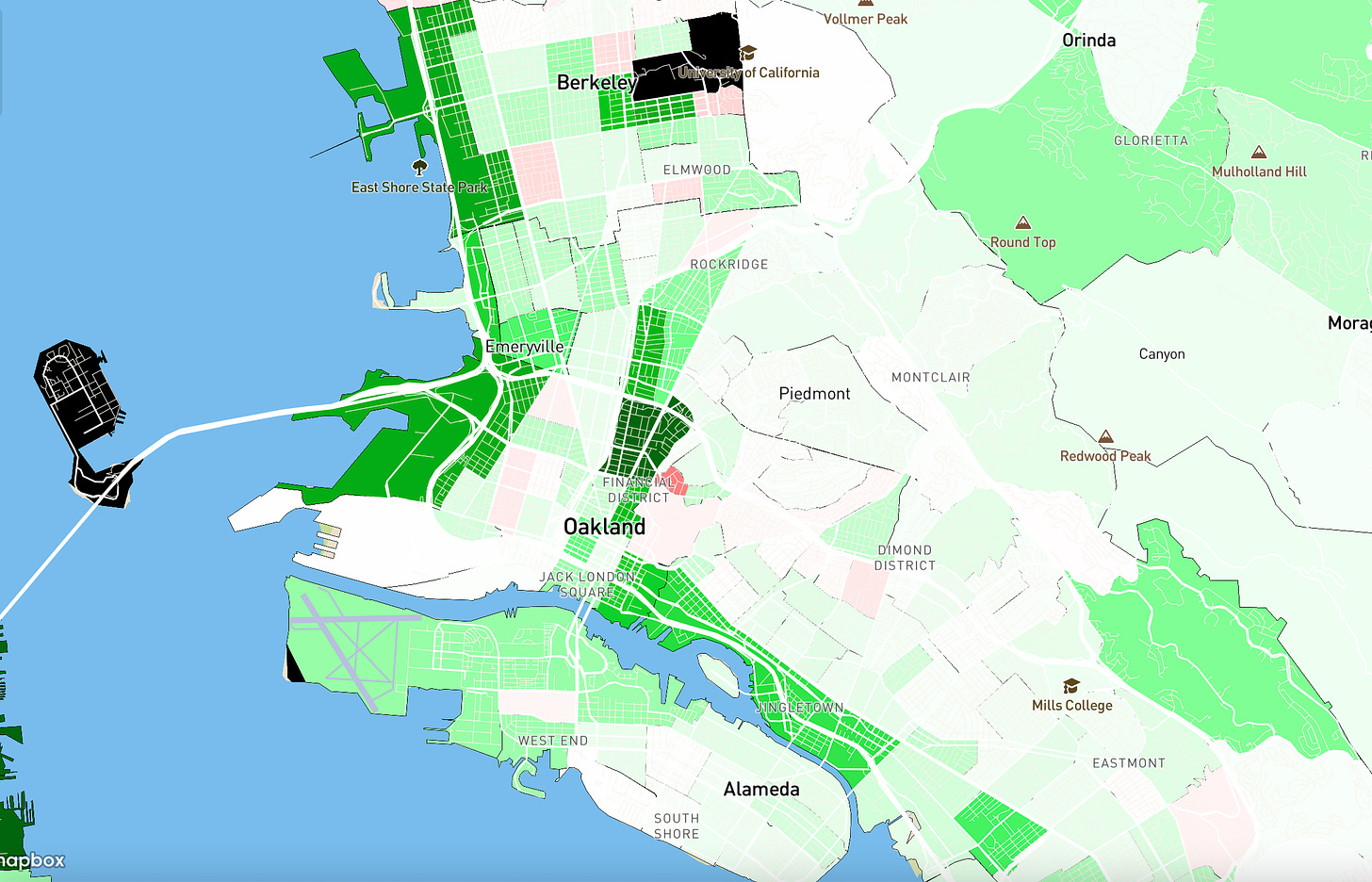

The Broadway-Valdez plan was the attempt to transform Broadway, which was an empty downtown strip with rows of parking lots for office commuters and car dealerships, into a residential neighborhood that would have the population to sustain local businesses. Suffice to say they succeed with thousands moving into Downtown Oakland and many homes built alongside them. Tracts in light green averaged around 500 additional homes, dark green 1,000 additional homes, white tracts are virtually zero additional homes and pink tracts indicate more homes were destroyed than built.

The map reveals that housing development in Oakland was largely confined along Broadway. Hundreds of homes were built in Jack London Square, particularly the southeast tract at the waterfront. Hardly any housing was added in Chinatown and the office-heavy Oakland City Center. Few homes were added on the west side of Uptown between West Grand and 14th Street, largely because it had already been developed in the 2000s as subsidized low income housing. Much of the private housing construction from the 2010s picks up a couple hundred units directly east of Uptown Broadway.

There was a huge 2,000 unit increase in homes along upper Broadway along “Auto Row” where the car dealerships are. Half were located on the Pill Hill/Koreatown side with some new development veering off onto Telegraph and the other half east in the Westlake tract directly east of Broadway.

Outside of downtown there was very sporadic development. There was about 600 new homes on the industrial edges of West Oakland which are townhomes. 367 homes in the Brooklyn Basin tract and another 300 each where the Fruitvale Village and Coliseum BART development is. Largely subsidized housing. Other than that, the vast majority of Oakland didn’t see any added housing at all. Highland and West Oakland appears to be marginally losing housing because wealthier buyers are converting duplexes into single-family units.

The Black population seems fairly consistent—neither large declines or massive growth in the Broadway-Valdez tracts. Toggle back and forth between the Black population and housing totals along the Broadway corridor. Note that the huge decline in Black residents in the Oakland City Center tract (4031) is due to the jail depopulating by 548 residents.

About 200 new Black residents moved into the Jack London Square tracts, 37 more Black residents moved into the east side of Uptown Broadway with the private housing development (13% increase), 192 more Black residents moved into the west side with the subsidized housing development (14% increase), 98 more Black residents moved into the Valdez tract and 40 Black residents appear to have left the Koreatown/Pill Hill census tract. In whole numbers these are just consistently stable or stagnant population growth.

Lets identify two Census tracts, one with and without new housing construction, but both with sizable Black populations, both beside each other and compare:

Pill Hill/Koreatown in 2010 was home to 1,255 Black residents, and Hoover-Foster in 2010 was home to 2,090 Black residents. Pill Hill/Koreatown added 1,014 homes in the last 10 years, a 55% increase in housing and Hoover-Foster added just 31 or an 1.8% increase in 10 years.

So how did both Black populations end up 10 years later?

As stated earlier, there are 40 fewer Black residents in Pill Hill/Koreatown. Hoover-Foster? 512 fewer Black residents. That’s a 3.2% decline in Black residents in Pill Hill/Koreatown versus 24.5% decline in Black residents in Hoover-Foster.

That seems pretty revealing.

The white population increased marginally more in the Koreatown/Pill Hill tract than they did in Hoover-Foster. But the 1,014 units of extra housing appears to have cushioned the Black residents from the gentrification blow in Pill Hill/Koreatown, probably since the newcomers moved into the new development instead of existing housing. Hoover-Foster, with no added housing capacity, forced newcomers and incumbent residents to compete for existing housing and over 500 Black residents were displaced as a result.

Lets be skeptical of that interpretation though and try to replicate similar results elsewhere. Lets go north to the MacArthur BART station and see if there’s a pattern.

West of MacArthur BART: Longfellow District. 2,848 Black residents in 2010. 45 homes built in 10 years or a 1.7% increase in housing.

East of MacArthur BART: west Temescal, including the MacArthur BART Towers. 975 Black residents in 2010. 580 homes built in 10 years or a 27% increase in housing.

54 Black residents were displaced from the Temescal tract including the MacArthur BART highrise and Longfellow?

1,019.

Yes, read it again: 1,019 Black residents had gone. 35.8% of the Black population of Longfellow disappeared versus 5.5% for the MacArthur tower side. If we looked at that as a weekly average, that means for every 4 days in the last 10 years, 1 Black person disappeared from Longfellow—just one Oakland neighborhood alone.

This is the largest decline of Black residents of any residential neighborhood in the entire East Bay and reveals that Northwest Oakland is ground zero for Black displacement and gentrification in the Bay Area.

West Oakland, which is also undergoing a large decline in Black people, is losing relatively fewer. West Oakland around the BART station only lost a few dozen Black residents likely due to the previous decade’s expansion of affordable housing nearby. Black displacement increases into the hundreds around the areas where many historic Victorian houses are located. The Black population however increases by 381 residents in the large tract featuring the Wood Street town home development. It’s also the only tract that built a considerable amount of housing in West Oakland—637 more homes. I dont know if affordable housing was built there or not so I can’t make judgement on this tract. 1,170 new white residents moved into this tract as well but similar to Koreatown/Pill Hill, the influx of whites does not create a net-negative in Black displacement evident in the Census. The remainder West Oakland neighborhoods particularly north of west Grand are basically one-to-one replacement of Black residents with White newcomers.

Now lets deploy some skepticism about our conclusions on the impacts of new housing. What if in North Oakland the development on the east side of the freeway was responsible for the displacement of Black people on the west side? The MacArthur tower is separated from the Longfellow neighborhood by a mere 6-lane freeway. That’s still certainly within the range of market influence. If one can see the MacArthur tower quite clearly from the Longfellow district, certainly one’s rents could be influenced by it too, no?

I think this concern is reasonable. But if the displacement was being caused by the new apartments and condos on Broadway and Telegraph, then why isn’t the amount of Black displacement identical or worse in the immediate areas it’s in? I’ll even cut extra slack here, why not identical as a percentage? Yet even then the percentages of Black displacement are significantly smaller in the developing tracts.

If we scroll up to the Sante Fe neighborhood directly north of Longfellow bordering Berkeley—quite a ways away from the MacArthur highrise—that tract has a considerable number of Black residents yet 6.3% more displacement than the Longfellow tract. Black displacement continues straight into South Berkeley where very few additional homes were added.

Lastly, look west of Longfellow for a minute at Emeryville. That Emeryville tract added 279 new homes and the Black population increased, not decreased, by 164 residents. Meanwhile, a big sea of uninterrupted Black displacement stretches north from West Oakland to South Berkeley, in all the tracts with about or fewer than 10 new homes annually. So it begins to resemble a trench where both Emeryville and west Temescal have a somewhat stagnant Black population, and then there’s a huge bomb of displacement in the middle between San Pablo Avenue and I-24.

It’s quite clear that what’s causing displacement in North Oakland is not the new MacArthur complex—unless that one tower behind a freeway is displacing Black residents as far north as South Berkeley. But it’s also not 100% clear how much new housing is stunting displacement, considering it appears its effects at reducing displacement seem fairly limited geographically.

Here’s two likely scenarios planners in particular should consider. Is it possible that the differences in displacement is due to:

The Black population being displaced from older housing in Northeast Oakland as much as Northwest (either from subprime or eviction), merely that Black people are moving into the new complexes (either in market-rate or inclusionary units), thus creating a tiny net-loss.

The Black population in Longfellow and Hoover-Foster is disproportionately homeowner and was more affected by the subprime mortgage crisis whose after-effects spread into the 2010s.

All Demographic Changes

The underlying cause of Oakland and the East Bay’s gentrification was San Francisco and Silicon Valley creating a lot of jobs and little housing to match it. In addition to the depopulation of whites from historically white and now prohibitively expensive enclaves.

Prohibitively expensive enclaves—made that way thanks to their failure to accommodate population growth—exchanged the least wealthiest white residents for upwardly mobile Asians with higher incomes. Asian migration was universal, growing all over the Bay Area including in the most wealthiest communities and notably out from Chinatowns and historic Asian enclaves. But Asian Americans are quite diverse and are showing signs of displacement too by moving into lower income communities like Richmond.

A very similar trend occurred with Latinos but largely in the displacement direction. Latinos too are similarly declining in historic touchdown sites for immigrants but they’re mostly headed for cheaper neighborhoods in the Bay Area. Latino population growth in Fruitvale has effectively been stemmed by housing costs while Latinos have been displaced en-masse from San Francisco’s Mission. The bulk of new Latino population growth has now shifted to Black enclaves in Deep East Oakland and Richmond.

Downwardly-mobile whites from the Occupy era and/or priced out of San Francisco’s Mission have settled into West Oakland and Fruitvale, much like the Summer of Love hippies settled into the Black neighborhoods of the Haight and Berkeley before them. These are generally the early signs of gentrification. Upwardly-mobile whites are currently expanding through Longfellow since their old spot Temescal and Bushrod got too expensive in the early 2010s. Temescal was the old-new spot after lower Rockridge got too expensive by the early 2000s, which was also the old-old-new spot in the 1990s as College Avenue/Elmwood got too expensive.

This wave of gentrification appears on a rendezvous with the senior level tech worker class who can’t afford South Berkeley anymore and are southbound through the Longfellow district. As indicated by all the house flipping. Final destination is West Oakland where they’re already replacing the first gentrification wave of whites. Non-tech middle management and nonprofit-type newcomers are settling into Eastlake, San Antonio and Highland now that they can’t make it in Temescal anymore, with the higher salaried ones going for the Black middle class communities in East Oakland like Maxwell Park.

Underscoring all of this is that the East Bay flatlands feature relatively affordable housing, urbanism, and safety from the firezones which are skyrocketing housing prices. A ripe environment for real estate speculators and house flippers who bought up houses during the Recession.

Black Decline in Deep East Oakland

Hundreds of Black people are leaving Deep East Oakland at twice the rate whites are moving in. Hundreds of Latinos are moving into Black neighborhoods like Elmhurst at an even greater rate. These are the characteristics of what academics call “Black Flight” (I hate this term), where middle class Black people leave disinvested neighborhoods. It’s probably a mix of that and also the poorest Black residents being displaced by increasing rents.

Violence in East Oakland is nothing new. I grew up in East Oakland and became accustomed to it. While homicides were at record lows in the middle of the 2010s, Deep East is still the city’s epicenter of shootings and Black death. There are many Black families who are considering leaving and there are many Latinos families that need bigger, relatively affordable homes and are moving into Deep East.

So does “Black Flight” count as displacement?

Most say no but I say yes. It may not necessarily count as gentrification, but it certainly counts as displacement. You can have lots of “gentrification” without any displacement. Take for example Emeryville, where lots of white and upper income residents have moved into the city, a.k.a. gentrification, but the Black population remains the stagnant or grows thus no displacement.

But displacement through disinvestment is still displacement. First of all, lets be clear, non-Black people, especially white people, are irrelevant to the conversation on violence. Yes, poverty intersects with the quality of life of brown residents such as trafficking targeting Latinas and Southeast Asian girls, or gang violence between Latino and Southeast Asian boys. But these are intra-community struggles. If you’re white or a newcomer, there’s no safer place for you than Deep East Oakland or any so-called “dangerous” neighborhood because you’re not the target. No one’s got beef with you. No one is going to mistake you for a rival gang member. No one’s going to shoot you.

But for the Black parent these things matter a lot. Every day, many of them dread the call. Where someone on the other side of the line informs them their child or relative has been shot. I’ve received this call. I’ve had more friends and classmates get murdered in East Oakland than I can count on two hands.

On a personal level, East Oakland data is rather interesting to me because I’m a part of this data. When the 2010 Census was taken, I was living in East Oakland and now in 2020 I live in Berkeley. Was I displaced? Well, yeah. Not by a definition as narrow as a rent increase or eviction, but by the quality of life.

As a teenager I couldn’t go out past 9, I was prohibited from owning red shoes, I couldn’t get mixed up with the wrong crowd, I was not able to walk on certain blocks. My street was littered with glass from windshields, my sidewalks were screwed up, the littering was constant, there’s repeated traffic violence and accidents. That was the fate of one of my closest high school friends, killed in a hit and run near an 880 off ramp. Conditions like these were the reasons I remember my neighbors in East Oakland chose to move. They talked about the nice suburban place they got, with the caveat that it was over an hour away. The new neighbors were South Asians and Latinos.

Yes, seeking out a better life elsewhere because your community lacks the investment to sustain your family’s well-being is displacement. Displaced by disinvestment. And the problem with “Black Flight” that academics don’t understand is that it is the opposite of White Flight. White families sold their homes to buy more expensive homes in the suburbs with federal subsidy. Black families are selling their appreciating homes to live in cheaper houses in the suburbs without much or any subsidy, especially after the subprime crisis.

But there’s also a lot of typical, involuntary displacement as well. Many Black households are headed by grandparents who pass away and their children can’t decide on who gets the house so they cash out. Or an emergency happens and the only asset of value you have is your house, so you reverse mortgage and if one slip up happens suddenly you’re foreclosed. That’s not unique to East Oakland however, that’s East Bay wide.

So with all this displacement, where are Black people going?

East County

There’s so much population growth occurring in the Bay Area’s new far-flung exurbs that my census algorithm has to N/A many of the tracts. But there was enough sprawl in Antioch and Pittsburg in decades prior for the results to be clear.

Nothing but Black growth in Antioch and Oakley as far as the eye can see. Many of the N/A tracts are whole new suburban sprawl subdivisions under construction by developers. 400 to 600 person increases in Black residents per Census tract. The largest developments are occurring near the nature reserves (and in the N/A neighborhoods we can’t see yet).

Huge expansions in housing development in the Neroly neighborhood straddling Antioch and Oakley, which are corresponding with these massive increases in Black residents. Thousands of new Black residents have moved into the recently built Oakley-Neroly development alone. Similar trends found in Tracy, which is outside the East Bay, and a newly developed suburb.

But this has coincided with an all too predictable pattern. As Black residents settle in eastern Contra Costa County, white residents leave—by the thousands. Old school white flight is underway in Antioch for a series of reasons. The most obvious: they don’t want to live near Black people and think the town is declining as a result. Secondly, the younger whites of Antioch and Oakley have the economic mobility to move out. Every tract, except the 2,000 white person increase in the new Neroly development, shows 21st Century White Flight.

If there is one constant in life it is that where white people want to live is where Black people cannot live, and where white people don’t want to live is where Black people end up living. Black communities are forced to play the game of Red Light, Green light entirely on the whims and preferences of where white people want to live each generation.

Conclusions for Local Policy

For the upcoming housing element, Oakland should re-examine its inclusionary program and evaluate how much affordable housing is being produced on-site as opposed to fees for 100% affordable elsewhere. Broadway-Valdez appears successful at both providing downtown with enough people and appears to be stunting severe displacement experienced on the west side of I-24. But we ought to see increases in Black residents along Broadway, not just stagnation or very small growth. Higher rates of Black population growth are occurring in Downtown Berkeley’s development and San Francisco’s SOMA neighborhood so why not Oakland’s?

Only subsidized housing nonprofits are adding housing capacity in East Oakland and extremely few for-profit developers show any interest in going into East Oakland’s high density zones. They and their inclusionary units can’t be relied on for sorely needed housing to combat displacement occurring today.

We know that Black and Latino homeowners tend to add “illegal units” in the form of unpermitted garage conversions to accommodate larger families or add neighborhood housing. Unfortunately, due to the cumbersome permitting rules, many of these homes are in poor condition. As Oakland and Berkeley plan a city-wide legalizing of fourplexes, programs should be crafted to assist disadvantaged homeowners in adding homes to their properties in safe ways. Only the community appears interested in adding housing in their neighborhoods and so they should be assisted.

Vacant housing all over Oakland is down (besides Broadway where there weren’t many housing units in downtown in 2010), with anywhere from 50% to 70% reductions. Yet the Latino population growth in Deep East Oakland far exceeds housing capacity. For example, take this Elmhurst tract (4096): 24 new homes plus 99 fewer vacancies equals 123 available homes. Nearly 1,000 Latinos moved there as the Black population declined, comprising 714 additional residents since 2010. Assuming an average Hispanic household size of 3.22, the number of available homes needed was 221 homes—nearly double what was actually available. That suggests severe household crowding. Assisting homeowners in creating multifamily housing including the legalization of RV/trailer dwelling units both on the streets, within driveways and yards, and city wide, are practical solutions dating back to World War 2’s emergency housing strategies.

Multifamily homes must be protected in gentrifying neighborhoods. Oakland’s Highland, West Oakland and Berkeley’s San Pablo Park are declining in total housing counts because wealthier buyers are eliminating duplex units for single-family conversions. This has often displaced tenants and results in a net-loss in housing. All cities should codify in their housing elements the recently passed anti-demolition state law (SB 8, formerly SB 330) that prohibit a net loss in housing units, displacement of renters or destruction of rent controlled housing without rent controlled or affordable replacements. East Bay for Everyone has blown the whistle on several developers that almost destroyed rent controlled units that the Oakland city government didn’t notice beforehand.

I hope the data at the very least tampers the belief that somehow building housing accelerates displacement. Some Berkeleyans love to fearmonger about the imposing density of the MacArthur BART tower. But in 2010, the four main census tracts that represent one of the East Bay’s oldest Black enclaves, South Berkeley, all had equal or hundreds more Black residents than the MacArthur BART tract. In 2020, every single South Berkeley census tract now has fewer Black residents than the MacArthur BART tract and hardly any of them added housing.

That’s Oakland’s future unless the Bay Area—yes the whole region—gets serious about housing.

Lastly, we need a Bay Area regional affordable housing trust fund. Because if San Francisco and Silicon Valley continue to add far more jobs than homes to reap the fiscal benefits from tech office expansion, then they should at the very least share those dividends and finance affordable homes in the East Bay to combat the population growth and subsequent displacement they’re creating.

(Post was edited to change “Ghost Town” to Hoover-Foster).

One thing interesting to note is that the population of Latinos in San Francisco increased from 2000 to 2010 and from 2010 to 2020. In fact, it has steadily increased since 1970. So while there was displacement from The Mission there was growth in other census tracts. I have not examined where though.

The White population has remained more or less stable since 1990 (there was some White Flight before that) and the Asian population boomed.

The Black population declined precipitously dropped from 1960 to 2010 but seems to have lessened since then, perhaps due to the building of affordable housing.

Instead of building more housing, we could instead prevent gentrification and displacement by removing public amenities, making the local schools terrible, ensuring crime is high, and making sure the housing stock is as terrible as possible...! Or at least that seems to be the message from some advocates against gentrification...

Interesting analysis and good case studies of the area—it obviously comports with a lot of the econometrics work (that is agnostic to "Black Flight" and all the other sociological phenomenon, but, in a pretty standard fashion, generally shows that housing is correlated to incomes, and holding down housing stock in areas of rising income will generally create housing inflation).

White/Black/Asian Flight/Following has been a pretty constant thing in the Bay Area (and other places, I'm sure). However, it's odd to me how stratified the Bay Area has always felt. When I was in the Northeast, especially New York, there seemed to be more integration—and, especially, much more of a Black middle-class. Admittedly, I was usually in urban areas out there, but even so (and even comparing to "urban" areas here). Obviously, it's not like there's none here and it's not like the Northeast is a "post-racial utopia" or something, but after coming back to the Bay Area after having lived on the East Coast for about a decade, it's been pretty jarring. I haven't looked deeply in the academic literature on the topic (though it does make some sense in terms of migration patterns and history), and maybe this was all just happenstance, but it is a bit disheartening.