Exclusionary Zoning, But in Poor Neighborhoods

Should poorer areas undergoing the threat of gentrification be exempted from upzoning or perhaps downzoned?

There’s an undercurrent of thought in the housing world on upzoning which is that it should be focused in wealthy neighborhoods while poor neighborhoods of color should be exempted through “sensitive community” rules. While the corollary, that low income areas should be downzoned is not explicitly stated, that is the implied reasoning of the proponents who seek to stop private housing construction.

YIMBYs and housing advocates more broadly have adopted this request and it’s actually become a popular rallying cry to “upzone wealthy neighborhoods!” And I’m all for that, however I find it ridiculous to base your entire housing advocacy around improving the land use of rich areas only. Nevermind that what qualifies as a low income area at risk of development-induced gentrification is by no means universally agreed upon.

But before we go further, nonpartisan polling is pretty consistent that the communities most in favor of zoning reform are Black and brown communities with whites the least in favor.1 2 3 But it’s not universally held, while working class communities rejected a housing development moratorium in Los Angeles, the Latino Mission District in San Francisco supported it at the polls. So before we exempt them from land use reform it’s worth asking: what suggests that strong density limits helps poor communities fend off gentrification?

Most research suggests that downzoning inflates home values or that it has no effect either way. An amalgamation of studies on the impacts on downzoning and density restrictions throughout the century in a report published in a UC Berkeley journal finds that downzoning either inflated home prices and or inflated the cost of construction and subsequently market rents in places like California.

The empirical literature on growth control, largely from California evidence, supports the case that supply effects dominate. In many studies, development restrictions are shown to increase price and bar the poor, thus exacerbating income segregation.4

Part of the logic for sensitive communities is that upzoning increases the potential use value and downzoning preserves the current use value, thus creating larger rent gaps. (“Rent gap” is a neo-Marxist theory on how gentrification works by measuring the potential profitability of income generating activities on land vs. the land’s current use.)

But it’s worth remembering that most people buying houses, overwhelmingly most of them, aren’t developers. They’re far more likely to be realtors and landlords if they’re corporate at all. So the common notion that say, allowing two homes would double land values because there’s two profit-generating homes that could be built, is ridiculous because most people won’t be using the parcel for that purpose and sellers know that. And anyone can open up Zillow and compare homes in areas where 2-10 unit multifamily housing is zoned vs single-family and usually see higher prices in the latter or no differences. Research from Othering and Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley suggests that as well.5

Not only that, but it’s kind of an open secret that residents in low income areas don’t really care what the zoning ordinance in low income communities are. Your average Black, South Asian or Latino homeowner and/or contractor that wants to convert their home into a multifamily is going to do it without a permit and regardless of what a zoning ordinance says — provided nobody snitches.

The lack of zoning adherence actually is bad because it causes homeowners to have to rely on shoddy contractors who make dubiously habitable spaces. This is the current situation in Oakland for example, where people are living out of garages as second units without any plumbing and electrical lines that don’t meet safety standards.

There’s also an element of criminalization that bothers me. Houses inspected with illegal multifamily units means working class homeowners are subjected to fines and possible removal or condemnation if the home isn’t made zoning compliant. I’m not comfortable turning working class communities into criminals for adding an extra home or several that weren’t allowed on some silly-colored document downtown.

All these issues aside, the only thing single-family zoning does anyhow is preserve a lot of old houses for buyers who want single-family dwellings. Rich people consume a lot of space and energy, a lot more than working class people, so single-family houses will always be the most appealing to them. Keeping only inefficient, single-family homes in poor areas while densifying affluent ones would just focus wealthy demand for that housing in those poorer communities anyhow—likely exacerbating gentrification.

I’m just not convinced that sensitive community exemptions either work or are necessary. Instead, upzoning should be coupled with renter protections to ensure tenants aren’t displaced by a speculator developer. We have made major strides on this with new state laws that ensure right of return, and appear to be working quite fabulously so far.6 But they only apply to rent controlled housing and need fine tuning and should apply to all rentals universally.

Most “development” happening displacing tenants is generally apartments at lesser density than existing structures, condo conversions of existing rental housing, or the conversion of 2-4 unit homes into single-families for wealthy buyers. Sensitive communities overlays don’t address these realities, they’re just a complicated tool based on theoretical possibilities for upzoning bills.

Now that doesn’t mean upzoning is harmless: a study out of Chicago found that upzoning increased property values while failing to produce more supply.7 But the takeaway from that study —a takeaway endorsed by the author himself — is that relegating upzoning to confined areas funnels capital onto those few parcels in the immediate term because those parcels become special. This is an argument for universal upzoning rather than spot upzoning of just certain areas or neighborhoods. The more areas exempted from upzoning, the more that spot zoning effect occurs.

Many people will point to several gentrified communities like San Francisco’s Mission District or Silver Lake in Los Angeles to argue that upzoning increases costs and displacement since these areas have seen new development and evictions since they were upzoned. There’s certainly truth to that but again, the Census indicates that the Latino decline stretched far beyond the couple of blocks in which luxury condos were built in San Francisco’s Mission. It does see displacement in developing areas, but it’s part of a broader area trend. Of course in Oakland there’s really no correlation whatsoever with Black residents and development as I went over previously.

I’d suggest this supports the latest research by the UC Berkeley Urban Displacement Project which found that in gentrifying areas, there was no impact either positive or negative, of market-rate development in the Bay Area on low income households.8 Likely, in my opinion, because the supply deficit was far too servere to be changed by a few luxury condos and much fewer subsidized housing.

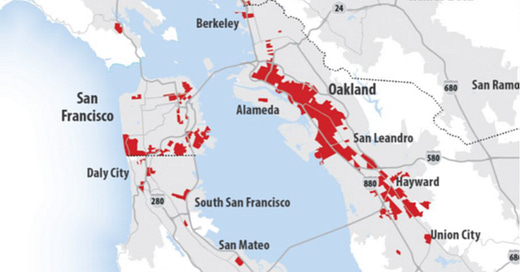

But a reminder that up until recently, almost all California cities’ priority development areas exclusively upzoned poor or gentrifying communities while leaving wealthy enclaves untouched. So upzoning has been tainted by that policy which has been reformed ever since a series of YIMBY-sponsored laws in California required governments to abide by federal standards on fair housing and upzone wealthy areas too.

In my opinion it doesn’t make much sense to by-right very high densities of housing in gentrifying areas because if they exceed eight stories and become steel construction it’s difficult to imagine them ever becoming moderately affordable with such expensive construction costs. But cheaper infill housing without density restrictions within existing heights seem pretty common sense and more affordable.

Eliminating exclusionary zoning in rich areas is a mere byproduct of furthering fair housing and making housing affordable, it’s not the entirety of what any pro-housing movement should be. Families living in lead-filled, gas station adjacent, seismically unsafe apartments deserve modern, mixed-use homes too.

https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/content/pubs/other/crosstabs_alladults0517.pdf

https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/s_917mbs.pdf

https://fm3research.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/320-929-CA-Voter-Views-of-Climate-Issues_FINAL.pdf

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90m9g90w

https://belonging.berkeley.edu/single-family-zoning-greater-los-angeles

“SB 330, stemmed the bleeding and effectively halted projects that raze [rent controlled] apartments in the city”. https://mv-voice.com/news/2021/04/15/massive-zoning-overhaul-in-mountain-view-would-increase-density-potentially-adding-9000-new-homes

https://yonahfreemark.com/2021/04/13/upzoning-chicago-impacts-of-a-zoning-reform-on-property-values-and-housing-construction/

https://www.urbandisplacement.org/maps/housing-by-block/

"Your average Black, South Asian or Latino homeowner and/or contractor that wants to convert their home into a multifamily is going to do it without a permit and regardless of what a zoning ordinance says — provided nobody snitches." - this is something that seems understudied, and it makes me concerned that *any* increased regulatory activity in a particular neighborhood - including deregulatory activity, including upzoning - will carry with it new code compliance expectations that are bad for existing low-income residents.

Interestingly enough the Latino population in San Francisco has been modestly increasing, both in total numbers and as a percentage of the overall population.

2000 - 109,504 (14.1%)

2010 - 121,774 (15.1%)

2020 - 136,199 (15.2%)

So while there has been a decline in The Mission and Excelsior there has been a gain in other areas, perhaps mirroring the Asian experience of "moving on up" to more suburban neighborhoods.