The Slow Death of AC Transit

The on-going fiscal crisis for AC Transit and how to reverse it in the future.

In 2020, shelter-in-place from COVID-19 began, people stopped riding the bus, bus operators were calling in sick, and my local bus agency, AC Transit, proposed “temporarily” closing lines. Among them was a bus that ranked the lowest in farebox recovery in Berkeley (the amount of money from tickets recovered divided by operational expenses), but had decent ridership in a key cross-town corridor called Ashby. The corridor of Ashby had been served by an east-west streetcar and bus line for over a 100 years. But that legacy came to an end when AC Transit ended the 80-line, stemming hospitals from accessing rapid transit stations, and leaving essential workers no access to bustling economic centres on the corridor for three years.

This was a clumsy cut by staff. The justification for the cuts focused on the operational expense rather than the ridership. It wasn’t the lowest ridden line in the city, but because it served low ridership corridors and a high ridership corridor, the operational dollar figure was higher than other lines with less riders. They should’ve just temporarily pruned everything else but the Ashby segment as Ashby by itself would’ve propelled its ranking in operational costs. Instead they just suspended the whole line.

Only after an aggressive and relentless campaign by East Bay Transit Riders Union, then pushes by subsequent community groups and board directors, was the Ashby segment restored on August 6th, 2023. When I realized the line was going to be cut, it motivated me and numerous others to start East Bay Transit Riders Union and do an aggressive outreach campaign. I was keenly aware of the consequences of normalizing severe transit cuts on key corridors. The many dead green and orange polls in my neighborhood of bygone AC Transit lines told me that despite these cuts being labelled as temporary, they were anything but.

The decline of AC Transit’s ridership, which carried 190,000 weekday riders in 2010 and withered down to 168,000 by 2018, is particularly confusing in the context of the economy. The Bay Area underwent an enviable economic boom. Cities and suburbs from Richmond to Fremont that AC Transit serves saw large population increases. Yet it’s as if AC Transit was stuck in an alternative universe where the local economy was perpetually stuck in a recession and its population declining.

The reason that AC Transit and hundreds of other public bus agencies like it are declining is because of austerity. I know its cliche, but the data backs it up. In 1991, AC Transit had its highest level of service ever and ridership was at a record peak. This was thanks to a “Comprehensive Service Plan” that transformed AC Transit into a grid-network of intersecting bus lines with free transfers and highly frequent service in urban core neighborhoods.

But the decline of federal subsidies for bus operations and the long-term ramifications of Proposition 13 capping property tax revenue, forced AC Transit to cut back on service increases and eliminate free transfers in a bid to stop fare evasion. Ridership plummeted by 8 million in a single year. A high-ridership grid-based bus network where people can easily transfer from one line to another doesn’t work if they get penalized with an additional fare, even a reduced one. Instead of grids, it gradually opted to combine many lines into unified singular routes, dipping into many corridors where possible, which often fails at both covering enough area and adequately serving major corridors. A “jack of all trades; master of none” conundrum AC Transit service routes have faced ever since.

Ridership remained stagnant throughout the 1990s as AC Transit chipped away at late-night service and ended all-night / “owl” bus lines. The stagnation was brought about from the decline in bus service counter-balancing the national increase in transit use. To increase ridership, Alameda County voters passed a half-cent sales tax conditioned on AC service restoration. AC Transit promptly reversed its many ‘90s cuts and increased service, and AC Transit reached a milestone of 70 million passengers.

But by 2002, the situtation reversed for AC Transit. The post-9/11 economy tanked transit ridership nationwide and AC Transit faced a major deficit of about $50 million. The need for cuts were dampened by a 2002 sales tax, but with revenue down, AC Transit cut 43 lines, combined and changed 102 lines and increased wait times in 2003. Gradual cuts continued in subsequent years, forcing AC Transit to cut more service than any agency in the Bay Area between 2003 and 2007.

Once the 2008 Recession began, the slow ridership rebound from service improvements following the service massacre of 2003 ceased. AC Transit faced high operator and labor costs, a pension crisis, and a severe cut in federal and local revenue that resulted in a $50 million deficit by 2011. This was the final series of major cuts pre-pandemic, and while the regional transit agency (MTC) was busy propping up expensive airport connectors and rail extensions in the East Bay for wealthier suburban commuters, AC Transit’s bus service was curtailed significantly. The agency was on the verge of total collapse, laying off tremendous amounts of senior and administrative staff, and 17% of bus operators. Additional cuts were averted due to the bailouts.

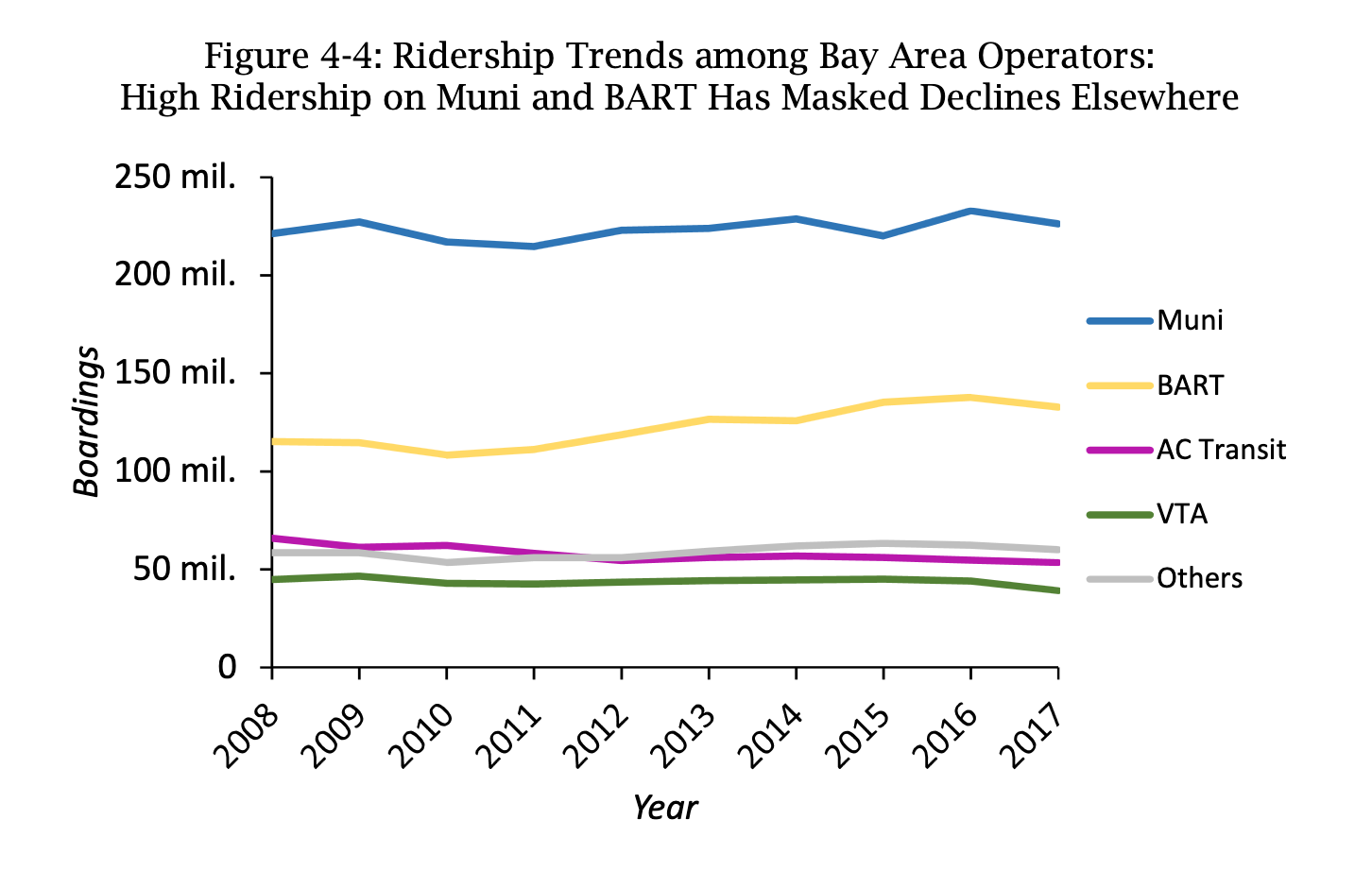

AC Transit again attempted to restore riders as the economy rebounded and high gas prices added more riders, but the revival of the early 1990s strong transit system failed. Between 2008 and 2017, AC Transit lost 12.5 million passengers — more than any other transit operator in the Bay Area, by far. All other suburban Bay Area bus systems, such as VTA, simply had flat ridership during this time. The growth of Uber & Lyft made BART-to-AC Transit fare charges far less lucrative, but was just salt on the wound to the host of service cuts that sent riders to automobiles and alternatives.

So what’s the takeaway here? Why is AC Transit so disproportionately harmed by economic trends compared to other agencies? Many activists over the years have noted how much MTC, which assists all Bay Area transit operations, favors funding rail transit over bus service. Bus service is disproportionately poor, primarily Black and Latino, while rail lines like BART and Caltrain are whiter and wealthier. During the severe AC Transit cuts of the 1990s and 2000s, MTC was subsidizing $2.78 per AC Transit rider vs. BART and Caltrain riders at $6.14 and $13.79, respectively. MTC still continues this disparity of disproportionate funding from its $1 billion funding for suburban rail lines and ferry service over inner-city bus operations.

Bus rapid transit in East Oakland that lost funding for barriers to keep cars out during the Recession, saw regional dollars instead go to an expensive and under-performing BART airport connector that glides over low income areas without any stops. While AC Transit was cutting bus lines throughout Oakland, Alameda Island and Berkeley in the 2000s, regional funds went to major capital projects like BART’s costly extension to SFO Airport, the suburbs and Caltrain upgrades. These projects weren’t bad but the neglect of bus operation funding because it wasn’t a fancy train to the suburbs killed AC Transit service, and put many people in cars clogging up freeways today.

MTC funding is one part of the problem, but the other half is local funding. VTA and Muni kept their bus ridership comparatively unchanged or growing while AC Transit’s fell. Santa Clara County and San Francisco, as a product of a having a distinct principal city, have tremendous and unified access to major regional employment centers and can direct their huge cash flows to assist Muni and VTA with relative ease.

The Alameda County and Contra Costa County board of supervisors are comparatively absent about supporting AC Transit, especially compared to BART extensions. The East Bay is also much more segmented and doesn’t have a principle city to guide funding and service discussions like San Jose and San Francisco (Oakland is just 25% of Alameda County’s population). So when major cuts happened in Fremont, Oakland wasn’t rallying to get a East Bay tax to save it. When Oakland lost all its transit lines in the North Oakland Hills, Berkeley and Alameda councils weren’t clamoring to save them. And there’s no reason to expect leadership from Alameda and Contra Costa county supervisors — they are incredibly inactive and absent on county transit issues (and most issues).

Now that ridership has declined, local governments barely care about AC Transit service compared to 30 years ago. Few local electeds ride AC Transit anymore or even know which lines run in their districts, unlike their counterparts in San Francisco. Oakland’s building whole high-density neighborhoods south of 880 and didn’t even bother to facilitate an AC Transit line to serve it, so the traffic crisis and AC Transit death glide will only get worse.

Point blank, here’s what needs to be done to save AC Transit long-term and increase ridership:

The Metropolitan Transportation Commission must cease subsidizing BART at two-to-three times the rate they subsidize AC Transit riders. Bus riders, who are disproportionately low income and minorities, should have transit fund at least on-par with suburban rail networks.

At the state level, we need to eliminate the commercial property tax cap imposed by Proposition 13. Had the reform passed in 2020, AC Transit would’ve gotten $29.3 million and been in a position to restore a lot of service.

At the local level, transit riders or at least people who care about AC Transit need to be elected to the Alameda County board of supervisors and initiate funding measures to boost AC Transit service and restore lines lost in the last 30 years.

AC Transit needs to be a lot more aggressive about the funding asks in major tax proposals rather than tagging along regional measures for a tiny cut. Distribute maps of whats possible with more tax revenue.

The cities of the East Bay need raise funds to restore their local lines back. Every city climate plan should have concrete steps of boosting AC Transit ridership in their city.

Cities undergoing large housing development need to stop requiring real estate developers fund private shuttles and direct that money solely to AC Transit for service. For example, Oakland City Council had the developers of Brooklyn Basin fund shuttles rather than pay for a route 18 extension to the neighborhood. Ridiculous. Have property owners institute free AC Transit passes to residents in exchange for no parking requirements as Berkeley recently did.

AC Transit must plan long term for a return to a grid-network with free transfers. Anything short of this will result in the eventual death of every AC Transit line that isn’t on a major corridor.

We need a mixed funding system like Seamless Bay Area so that BART to AC Transit transfers could be completely free and you aren’t penalized for using multiple transit agencies.

AC Transit needs to re-examine its transbay service amid remote work and BART well below capacity and transition those lines to local service routes.

Riding AC Transit will always have a tremendously lower carbon footprint per-capita than driving, regardless of whether the bus is diesel. While fleet electrification is nice, it doesn’t make a dent in carbon reduction compared to reducing car trips. Funds should go to bus service and not capital projects where possible.

Chris Peeples, a 24-year longtime AC director, told a group of transit activists in 2020, lightly paraphrasing: there has been many AC Transit bus rider unions before you to stop service cuts and every single one has failed. If we want a bus every 4 minutes like Paris, it takes money for the bus and dense housing. Instead, the regional programs subsidize wealthy, suburban rail and airport transit while buses in the cities serving low income people get much less money.

The Bay Area’s second most-dense region is increasingly opting for automobiles in neighborhoods built for mass-transit. The exact opposite of the transit and bike revolution in Paris. If we don’t fund the bus, there won’t be room left for anything in the East Bay besides cars.

“The Bay Area’s second most-dense region is increasingly opting for automobiles in neighborhoods built for mass-transit. The exact opposite of the transit and bike revolution in Paris. If we don’t fund the bus, there won’t be room left for anything in the East Bay besides cars”.- Darrell Owens

This condition from a state with democrats in majority control of government. A state that will outlaw the sale of gas powered lawn mowers by the end of 2023 in its perceived impact on climate change resulting only in negatively impacting the working class. Starting with austerity efforts by Ronald Reagan and right on through two terms of Clinton and Obama, and currently Biden, there has been a controlled demolition of the working class with no abatement in sight. Stop voting and donating to either political party. We live in an oligarchy that does not care one bit for the working classes. To quote the great federal court judge Constance Baker Motley, “ The greatest challenge with us into the next century will he class warfare. What to do about those of all racial and ethnic groups left behind by our latest economic revolution will challenge us all”.

All of us regardless of ideology must come together to confront this challenge to meaningfully restructure our society and improve the lives of working people and families.