Why Transit In Oakland Sucks

If we aren't serious about rapidly expanding public transit, just eliminating parking requirements won't eliminate the need for parking.

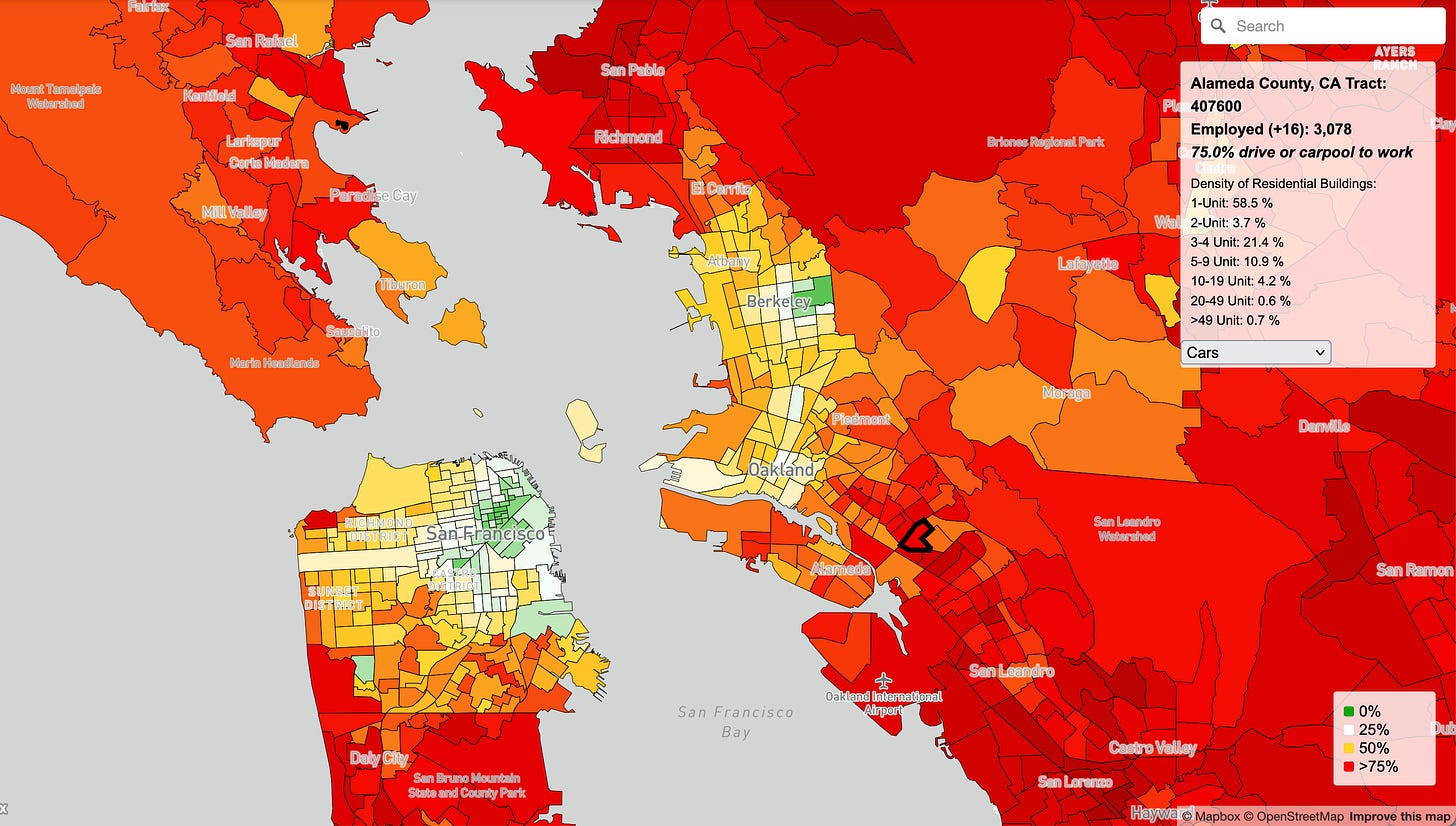

I hate to admit it but I find myself using my combustion engine to get around much of the Oakland-Berkeley area, particularly areas that aren’t served by a direct bus line or the bus takes five times as long as driving. It’s frustrating since the Berkeley-Oakland area ranks in the Top 5 non-car commuter U.S. metropolitan areas. I still take public transit to work since my office is located in a city center but in the remote work age, non-commute tasks to non-city center locations is unnecessarily long, convoluted or even impossible without a car. I could sit here and lie about my commitment to car-free living, but instead I need to emphasize that if I — a hardcore urbanist — am finding it difficult to give up my car in a dense metropolitan region, something’s wrong.

Donald Shoup, who passed away this week, was one of the great scholars pushing for a new American urbanism that wasn’t dependent on driving. He opposed parking requirements, a form of local legislation that mandates new housing and commercial development build parking spaces. Urbanists had three main issues with parking requirements: (1) parking is unprofitable real-estate subsidized by higher rents including rent paid by non-drivers; (2) they subsidized driving when that money could go to subsidizing alternatives to driving; (3) they make it easier to drive.

In the 2010s, the big case for ending parking requirements was mostly a stick over carrot approach: we subsidize automobiles so everyone drives. If we turn off the subsidy, people won’t drive as much. There’s a lot of proof backing this theory up, such as the awesome Congestion Pricing program in New York City. An imminently successful system of tolling drivers has pushed many motorists onto public transit, freeing up traffic for people who actually need to drive and increasing transit ridership.

Although San Francisco has not implemented congestion pricing, the limited space on the Bay Bridge, the lack of free parking in the city, aggressive parking enforcement and expensive parking garages forces thousands of commuters to take public transit to work. This is why San Francisco-bound commuters rank second only behind New York City in car-free commuting in the United States. A strong stick helps dislodge people from their cars.

When I worked for a low-income housing developer, I reduced parking requirements for two projects (one in Oakland and the other in Milpitas, California — both near BART stations). Our parking approach was rewarded with federal grants that rewarded low parking, transit-oriented developments because they were premised on the idea that we were creating climate sustainable, car-lite communities. I justified these reductions by conducting surveys finding that at least half of downtown parking spaces in select Berkeley and Oakland garages went unused.

Unfortunately, upon reviewing these now finished housing complexes, I’m starting to realize that too many sticks and too few carrots isn’t working. I was talking to a former co-worker at the low-income housing developer overseeing the leasing process for applicants at the complex adjacent to the Coliseum BART station in East Oakland. She admitted to me, rather begrudgingly, that despite a tremendous housing crisis in the Bay Area and Oakland being covered in homeless encampments, they were taking a longer time to fill vacant units than they had expected. Since my prior occupation at this developer included writing software analyzing housing waitlists where thousands of people waiting for a space was normal, I had a difficult time understanding why.

My old co-worker admitted that the lack of parking enabled by reduced parking requirements near transit stations made it harder to lease-up low-income and unhoused families. Many of these families used their cars to get to work since they’re low-income and often didn’t work in the office-oriented city center where BART trains serve. Or they needed their cars to take their kids to school and Oakland has no school bus system for its prolific charter school network. The local AC Transit lines are too infrequent to run errands or get to the other side of town for work. If their jobs are located south of Oakland, the BART stations often aren’t near where they work.

When given the choice between stable housing and very limited mobility versus unstable or delayed housing but near-unlimited mobility, some low-income families will opt for the latter just to keep their cars. Or they’ll give them up begrudgingly or try to sneakily own a car and park it somewhere on the street. This isn’t in a rural fringe; it is East Oakland. A dense, urban suburb and right beside a BART station and several AC Transit bus lines.

Is this an irrational decision on their part? No. Living next to a BART station certainly reduces the incentive to drive to the major office centers by car. But if you’re in a lower-income household, it’s likely you don’t work in those centers. Bay Area Rapid Transit, in terms of layout, was a car-oriented, suburban-first transit system that spent the last half-century not creating a single infill station in population and job dense, blue-collar areas in the heart of the Bay Area like Oakland.

BART was designed by 1950s planners who were only interested in serving mostly white, suburban areas and saw urban stations in Oakland and the East Bay as either an attempt at area redevelopment or something to be ignored. This 1950s urban planning philosophy drew the ire of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with his denouncing of the BART-inspired counterpart in Atlanta:

Urban transit systems in most American cities, for example, have become a genuine civil rights issue — and a valid one — because the layout of rapid-transit systems determines the accessibility of jobs to the black community. . . A good example of this problem is my home city of Atlanta, where the rapid-transit system has been laid out for the convenience of the white upper-middle-class suburbanites who commute to their jobs downtown. The system has virtually no consideration for connecting the poor people with their jobs. There is only one possible explanation for this situation, and that is the racist blindness of city planners.

While the latest urban planning trend in California is to densify transit stations (State Senator Scott Wiener just proposed a new transit-oriened development bill this year) densifying transit stations alone is woefully insufficient. How rail transit has been designed in most American cities is pathetic and inequitable, with most infrastructure built generations ago with different philosophies, social attitudes and economies in mind.

Building neighborhoods by transit without improving it dramatically is going to lead to us failing to hit our emissions reduction targets. It’s absolutely true that people who live by BART drive less than those who don’t (note the MacArthur BART housing project has the lowest car dependency in the entire city; good AC Transit lines nearby), but whether someone decides to abandon their car altogether really depends on the quality and range of transit. Right now, Oakland is creating transit-oriented communities where people drive less, but not ones where families can comfortably become car-free. That’s good for vehicle emissions but developers still have to build a parking space whether the car is used for jobs and errands or just errands.

Another big issue for tenants in these new projects is that Oakland’s bus system — AC Transit — is an infrequent and declining bus system far beneath the quality warranted by a city of Oakland’s size. AC Transit started off as the East Bay’s interurban transit system, but since the advent of BART in 1972, it has had no vision of what it’s supposed to be. AC Transit initially had interurban routes that BART tracks eventually followed so AC focused on getting people to BART stations. But this has proved ineffective because BART is a poor urban metro system and skips right over high-density neighborhoods, necessitating AC waste money shadowing BART routes anyways. The lack of fare integration between BART and AC Transit makes it less economical to bus to the station when you can drive and not wait 20-40 minutes for a bus.

Unlike San Francisco, Oakland is a comparatively easy city to drive into so the stick approach doesn’t work as well. The state bulldozed many neighborhoods to connect Oakland with ugly freeways, many of whom are lowly-trafficked and redundant. Oakland’s abundance of free parking means it’s illogical to not drive in Oakland since, ignoring ownership costs, the actual trip won’t require any payment and will be four or five times faster than public transit.

Why hasn’t Oakland and the urban East Bay’s public transit system been improved even as the city is more congested with population growth? Why does Oakland have significantly worse bus service in 2025 than it did in 1990, despite having 40,000 more residents today? Why has San Francisco been building out new subway lines and streetcar routes in areas they’re redeveloping for the last 40 years, while Oakland — whose population increased by 12% in the last decade alone — hasn’t added a single new rapid transit station or line since 1972? Why does Oakland have basically zero plans in the works to expand fast, rapid transit in its city — except for a regional rail plan that mostly is about passing through West Oakland?

San Francisco benefits from having its much superior public transit system organized by one agency (Muni / SFMTA), funded by one powerful organ (the Mayor’s Budget; approved by the Board of Supervisors) and managed by one person (the Mayor-appointed manager). This is why public transit plays such an influential role in San Francisco politics: the Supervisor and Mayor you elected directly run on issues pertaining to Muni service.

In contrast, East Bay transit is comically disorganized, which sucks because unlike BART in S.F. which goes down one corridor, BART in Oakland incidentally covers more neighborhoods. Most residents have no idea who their AC Transit representative is or if they even have one, so they complain to their local city councilmember. The city council then has to formally communicate to their AC Transit representative requesting service improvements. However, the ACT board director does not run AC Transit but oversees it. Attempts by directors such as director Sarah Syed to communicate to AC’s general manager about improving service (such as not eliminating bus service on Broadway in Downtown Oakland after-hours) has been sanctioned and criticized by other board members. This leads to a political culture of indifference and laziness where there’s no imperative to improve service because AC Transit races are noncompetitive and nobody holds them accountable or even knows they exist.

Funds to expand AC Transit service are received from taxation via the district which spans over part of Alameda and Contra Costa county — many areas with not a lot in common. To improve service in Oakland, either the AC Transit district would have to put up a tax measure during the election or the Alameda County Board of Supervisors has to allocate funds or raise a tax. AC Transit directors are unusually reluctant to put up big tax measures or advocate for themselves because there’s no political pressure to do so; most people don’t know they exist. Most Alameda County residents don’t even know who represents them on the county Board of Supervisors or what it does since they live in incorporated areas. Alameda is one of the most incompetently-run counties in California who receives very little scrutiny because its function is obscure to a population that overwhelmingly lives in an incorporated area.

That’s three-levels of local government you have to get through (city, county and special district) to improve bus service in Oakland the urban East Bay. By the time you get to the second or third agency, all concerned citizens can do is just throw their hands up, and that’s exactly what’s happened. Since 1990, AC Transit has dwindled away from a once large transportation network with a lot of political activity to an infrequent shuttle system useful on just several, high frequency corridors with very little local political engagement. Residents without a car living in transit-oriented BART developments in Oakland or dense neighborhoods have all their errands, social life and children’s mobility at the mercy of a dwindling bus network whose lines run 20 minutes to an hour. Very few families will give up their cars to live like this.

Eliminating parking requirements is still obviously a worthwhile goal since it stops unnecessary amounts of parking to be built. There’s not a lot of justification for keeping them since developers want to lease up their buildings and aren’t going to build less parking. Again, many garages I surveyed were half vacant so parking requirements were creating surplus parking that wasn’t needed.

But local government or politics has not stepped up to the plate to transition us into a sustainable future where parking lots next to transit stations aren’t necessary. We should have parking maximums near transit but it’s not feasible without counterbalancing with initiatives to increase alternatives to driving. The latter has not materialized for public transit.

Oakland City Council is the worst body at advocating for improving its own public transit system in the Bay Area. Oakland builds a brand new neighborhood that’ll usher over 7,000 new residents in high-density apartments and can’t even bother to coordinate a single bus line to and from nearby Lake Merritt BART station. Let alone getting started on an even closer San Antonio BART station that can be walked to like any developed nation would’ve done. San Francisco would’ve done it — and (mostly) did it with their SOMA developments — but Oakland can’t be bothered.

Former BART director Rebecca Saltzman concurs, bewildered at how much Oakland leaders did not care about public transit during her tenure. Despite numerous chances for Oakland to radically expand public transit, city councilmembers showed unusual indifference about transit compared to even far-flung suburban representatives.

The distance between some Oakland stations is just wild compared to the standard in any other urban area in other parts of the country. So it’s unfortunate that we didn’t [build more BART stations in Oakland] it 20 years ago. It’s been surprising to me [that] Oakland has taken this long to advocate for itself on infill stations because if they had done it 20 years ago when BART was extending to just about everywhere, they could’ve had them.

Oakland city council pushed for the BART Airport shuttle and they couldn’t even bother to plan a station in the neighborhoods between Coliseum Station and the Airport! A station which could’ve helped both connect service workers to a plentiful blue-collar job zone and revitalize a now severely declining corridor. Despite BART noting numerous times the tremendous gaps in stations such as near the Children’s Hospital or through East Oakland, tee-ing up Oakland leadership to push for more transit stations, the city councilmembers showed zero initiative to plug these gaps.

Part of the problem is that Oakland politics just sucks: everybody runs on crime issues, encampments, union influence, maybe housing issues but transportation is not at the forefront of city hall despite it being at the forefront of Oaklanders’ lives. In this article by The Oaklandside talking about an infill BART station in Oakland’s dense San Antonio neighborhood, I’m a bit stunned by the relative ambivalence about this obvious, plain-as-day infrastructure necessity.

She said she talked to Robert Raburn, a BART board director, and staff from District 2 Councilmember Nikki Fortunato Bas’ office. They were supportive, Wong said, “but said there needed to be more noise from residents.”

While Oakland needs more noise, suburban Fremont and Dublin are building infill stations because their local political culture just cares more. Dublin built an infill BART station next to a shopping mall. Fremont is about to start construction on a suburban infill station in a neighborhood with a population of 6,000 people per square mile. This Oakland neighborhood is 16,000 people per square mile, it should’ve been done 50 years ago. Why do people have to beg and start a bunch of noise for such obvious, badly needed infrastructure?

If we were governed by French socialists and liberals, the San Antonio BART station would’ve been built a long time ago. The French government under left-liberal leadership doesn’t wait 50 years for RER (the Paris version of BART) stops in lower-income communities. They run on building them, get elected into local and regional offices, and then do it quickly. This is a cultural problem with the East Bay and American urban planning at-large: its process over outcomes and the outcome is nothing ever gets done. Public transit in the Oakland area has gotten so bad I’m contemplating moving to San Francisco and just abandoning the East Bay to its car-oriented fate. San Francisco appears to be the only city in California that cares enough about public transportation that politicians respond to local needs.

I’m even a bit frightened about my decade-long initiative to removing parking spaces at the North Berkeley BART station for housing. I had figured that the erasure of the parking lot would push locals to invest in public transit, but as the development is about to begin, we haven’t seen any push on improving local bus transit. The North Berkeley BART area has fewer bus lines today than it did 15 years ago, and Berkeley seems less concerned about public transit in 2025 than it did in 2010 (when it was busy killing bus lanes that would’ve increased transit ridership. Fools).

I’m scared that when the San Francisco economy comes back, there will be high demand for parking at the BART station and people will curse the future development being served by one measly bus line. I’m frightened that future residents will own cars because the nearest grocery stores are not accessible by public transit and we don’t have the parking spaces for them.

I strongly resisted owning a car until I was 25 years old and now that I have one at 28, I can’t help but admit that it has made my life a lot easier. Taking a 50 minute bus ride from north Berkeley to Lake Merritt, Oakland which comes every 40 minutes, versus 15 minutes with a car whenever I want is just not tolerable for a real city. If the urbanist movement doesn’t take as seriously improving and funding public transportation infrastructure as it does reforming zoning, all we’ll be doing is create a new generation of high-rise sprawl.

As for Oakland and Alameda County, here’s what needs to happen if the city and region is serious about reducing 83% of its carbon emissions by 2050 as is stated in Oakland’s climate plan. If it’s not serious then just say so. I can move to San Francisco and we can stop pretending Oakland is anything but a suburban driveway for San Francisco commuters. Remember, transportation accounts for 24% of Oakland’s emissions.

Alameda County Board of Supervisors needs to map out where in the East Bay needs frequent bus service, including any bus service at all, and stop the 30-year decline of AC Transit. We then need to raise a tax to make this happen in the next two years. This should’ve been done 14 years ago. The board needs to be at the forefront of the East Bay’s transportation issues and not an obscure board people barely know.

BART and AC Transit need to be administered by the same agency, or at the very least have the same fare system and structure. Paying double fare for the crime of not driving to BART is irrational and attempts to coordinate in the last 50 years have failed.

Oakland leaders need to have a master plan for how they envision a future of extensive, rapid, rail and bus transit within their city to accomplish a 50% reduction or more in vehicle miles traveled in Oakland. That plan needs to be ambitious. San Francisco leaders are talking about Geary subways and North Beach subways after just inaugurating a new Chinatown subway. Oakland has no rapid transit plan for MacArthur Boulevard or Broadway, and no plan for infill BART stations in North and East Oakland. The only thing Oakland has done of major significance is beef up San Pablo and International with bus rapid transit. Notably, International Blvd bus transit is the only form of transit in Oakland that has higher ridership today than it did a decade ago because they invested in better service! A tiny spur through West Oakland connecting Emeryville Amtrak to another Transbay Tube is Oakland’s only rapid transit extension plan and it’s insufficient. Oakland needs to stop having its transit infrastructure just be a byproduct of being passed through for other cities.

Whether Oakland wants a real city with a real climate plan has yet to be seen. Yes, bicycles are important too but the Bay Area is not going to shed its car obsession with bikes alone. Public transit is equally important.

Hopefully the next Mayor of Oakland is serious about transportation and climate change. In the meantime, the Oakland City Council District 2 seat — where the San Antonio BART station should be built — is coming to a special election. Ask the candidates what they’ll do to improve BART and AC Transit service on February 18th at this forum!

I feel your frustration Darrell. Living in the East Bay for 8 years without a car, I also found myself extremely frustrated when relying on AC transit. From the embarrassment of convincing friends and family to take the bus with me only to have to wait 30 minutes after a bus gets cancelled, to constantly being late to events, and to the absurdity of looking at google maps and seeing driving time of 15 minutes and bus time being an hour, I ended up buying an e-bike and pretty much never taking the bus. Even though riding on the East Bay's disconnected bike infrastructure among dangerous and distracted drivers raised my blood pressure 1000% and I was almost killed by driver ever few months, it was the only way for me to get around reliably without a car.

I'm not sure how we change the governance structure such that the people making transit and funding decisions are more directly accountable to the public. Something like Seamless Bay Area's plan or even just merging AC Transit into BART would help with coordination, but would the decision makers still be too far removed from accountability to the voting public who ride transit? The East Bay cities are all probably too small to have their own systems like SF does, although maybe Oakland could have it's own. Of course a big influx of public money into transit operations would help, but short of finally getting a mega measure on the CA ballot or passing and Prop 15-esque split roll I'm not sure the big money is coming any time soon.

Anyways I live in Vancouver now so I have decent transit finally. But I still visit often and want the East Bay to thrive. If there's some way I can help from afar hit me up.

Great analysis. I’m glad you mentioned UCSF Children’s Oakland. Not only does BART skip past it, there’s not even an AC transit bus stop there! (Relatedly there’s an unprotected crosswalk between the hospital buildings that cars zoom through all the time, endangering families and staff. That whole area is built and maintained by Car Brain.)