A lot of people have no idea what “affordable housing” means. The way the public, including politicians and journalists, uses the term “affordable housing” is as a blank canvas for imagining whatever housing they’d like, rather than what it actually means: subsidized, rent regulated, usually awarded, housing. Common articles like these (which I’ll breakdown in my next piece) make statements like “The city/region exceeded its luxury high rent housing targets but fell well below its affordable targets.” In reality, very few jurisdictions plans for actual luxury housing, unless its single-family mansions. So what’s affordable housing, luxury and market-rate mean? In terms of the buildings themselves, land, construction and materials: market-rate and affordable housing are mostly the same things.

Since the 1960s, “public housing” had negative connotation with racial segregation, crime and declining property values. The housing realm struggled with ways to brand low rent housing projects that would not immediately conjure up associations with the oft-maligned “projects.” By the late 1970s, policy makers moved towards long interchangeable terms like “low rent housing” and “subsidized housing.” Not just because of advertisement but also because by mid-1970s, 44% of housing starts were federally subsidized and privately-owned, providing cheaper housing by financing private developers.

But “subsidized housing” was an icky term. It communicates that the social good of providing housing to those the market will not help has to be paid for, presumably by the public. At a time of welfare reform and austerity campaigns, nonprofit builders of subsidized housing needed to obfuscate the source of funding away from “government”, “public” or “subsidy.” This is why even today, demand-side subsidies for housing like Section 8 vouchers that are not well obfuscated with “affordable housing” or some equivalent are frequently ostracized and discriminated against by landlords and neighborhood associations.

By the 1990s, the nonprofit builders and policy makers settled on a comfortable term that laid emphasis on the benefits to the consumer rather than the producer: affordable housing. “Affordable” had long been an advertising term in the private sector to indicate certain market goods that were cheaper. The subsidized housing industry and anti-poverty nonprofits quickly labelled everything they could with the effective marketing term: affordable. (For example, market-rate housing depreciated in price was re-branded “naturally occurring affordable housing.”)

It marginally worked. People were less likely to be hostile to “affordable housing”. Many communities liked to pretend it referred to middle class housing for people like them — neither high-end luxury or low-income and problematic. But the broader public became confused on what affordable housing meant over the years. Now the public broadly believes it is privately-built housing priced at non-luxury prices that one can acquire on the market.

Many don’t realize that this is subsidized housing often reserved for low and very low income households that can only be acquired by waitlist and public financing (or extraction from elsewhere) to build. A.K.A. modern quasi-public housing. The buildings themselves often are indistinguishable from market-rate complexes to people unfamiliar with development, done on purpose to prevent stigmatization the public housing of old faced. Oftentimes anti-gentrification activists confuse modern 100% low-income housing complexes for luxury condos.

Attend a city council meeting over a housing development and people speaking out in favor of “affordable housing” often aren’t asking for a tax or budgetary allocation to finance their demands. Their demands are usually that private developers simply provide “affordable housing” rather than what a developer is usually proposing which opponents think is expensive, anti-family or out of character development. Developers refusing to provide affordable housing is simply so they can acquire excess profit, they say. Well-intentioned but reveals why people don’t understand why housing is so expensive and what affordable housing does.

Of course a real estate developer’s goal is to build and sell their housing as soon as possible while making a profit. In most of California, a developer can expect profit between 6 - 18% with an average around 11%. In the trifecta of real estate: building (developers), owning (landlords) and selling (realtors), building is by far the most risky venture. Most developer capital goes to construction workers being bid on by other developers, the purchasing of material goods subject to global economic headwinds, and most developer capital is borrowed. Banks won’t lend unless a developer can demonstrate a building is more profitable than the loan for several years and rising interest rates made many construction projects too expensive to proceed.

In a market system, unless you’re living in the home you build, few would bother developing homes unless they make a profit. This is where co-housing comes in. Co-housing is a type of social housing to solve the developer profit-seeking problem by eliminating the for-profit developer altogether. A community of people pool money together to build housing for themselves and rent or mortgage their units at the cost of construction there after. In simple Marxist terminology: the worker (and consumer) is commandeering the means of production.

For example, a group of 12 people propose to build 20 homes and look for would-be new community members by selling the remaining 6 at-cost of labor’s inputted value (a.k.a not by market value; surplus profit) to help finance the construction loan. The 6 - 18% surplus value making up the profit at behest of developers is removed from the home price, instead the home price reflects the cost of making their home, alone. To quote a co-housing project’s website in Sacramento: "Your price is tied to actual cost, not what the market will bear."

It’s a great idea but in Northern California, co-housing projects in Berkeley, Fremont and Sacramento, while remarkable, haven’t produce low cost housing. The Berkeley homes are projected to span between $900,000 to $1.5 million in a market where median home prices are $1.5 million. In Fremont, it’s $800,000 to $1 million in a market median of $1.3 million. And in Sacramento, it’s $400,000 to $600,000 in a market median of $500,000.

The developer middle man has been removed and yet housing sold at-cost is only a couple hundred grand short — at best — of median sale prices. Why? Because “affordable housing”, “market-rate housing” etc. are meaningless terms in how they’re used. High housing prices reflect among several things, expensive construction costs. The only difference is despite the identical cost, affordable housing is deed-restrict to be sold or rented well below its costs in expensive construction markets, while market-rate housing is sold for cost of construction plus the profit venture.

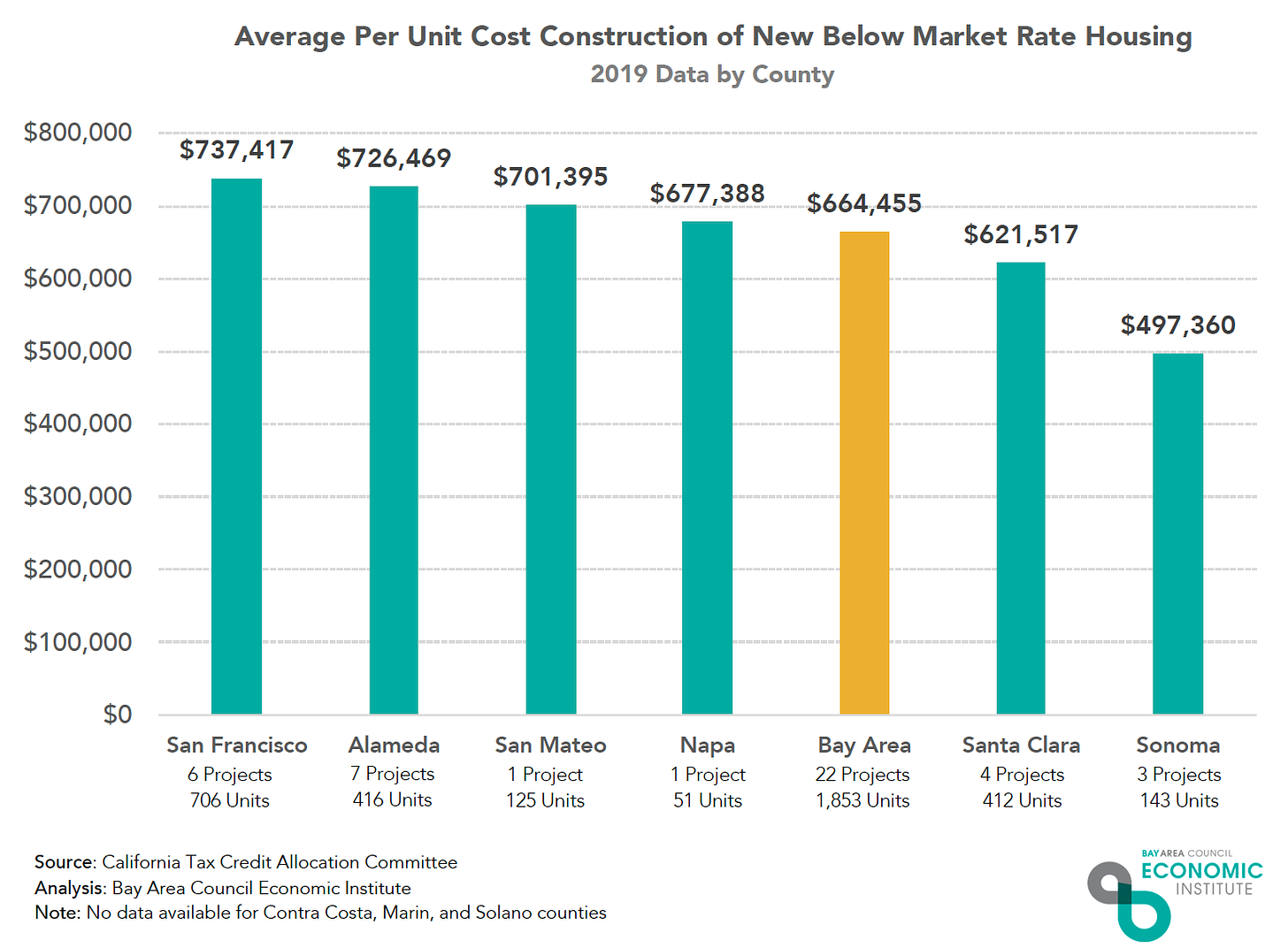

Affordable low rent, subsidized housing often exceeds the already high costs of market-rate housing construction, due to differences usually in labor standards, difficulty in acquiring a accumulation of time-sensitive financing, and the higher level of scrutiny publicly-subsidized projects receive than private. This, on top of all the regular housing cost burdens exacerbating private development costs. In the Bay Area, low income, subsidized housing is often three-quarters to $1 million per one unit in a complex.

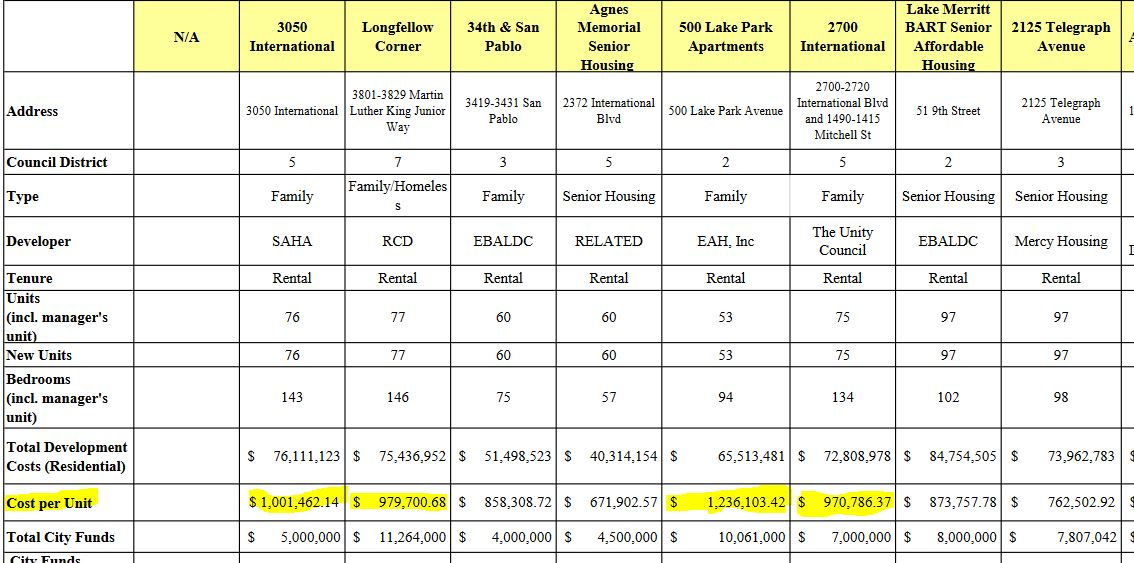

In Oakland, subsidized affordable housing projects span $600,000 per home to over $1 million, with the lower end projects generally being only studios and parking free. Note the higher bedrooms generally predict higher costs in this survey of low income development projects. This is often why private developers prefer small studio and 1-bedroom units vs. larger bedrooms for families in condos.

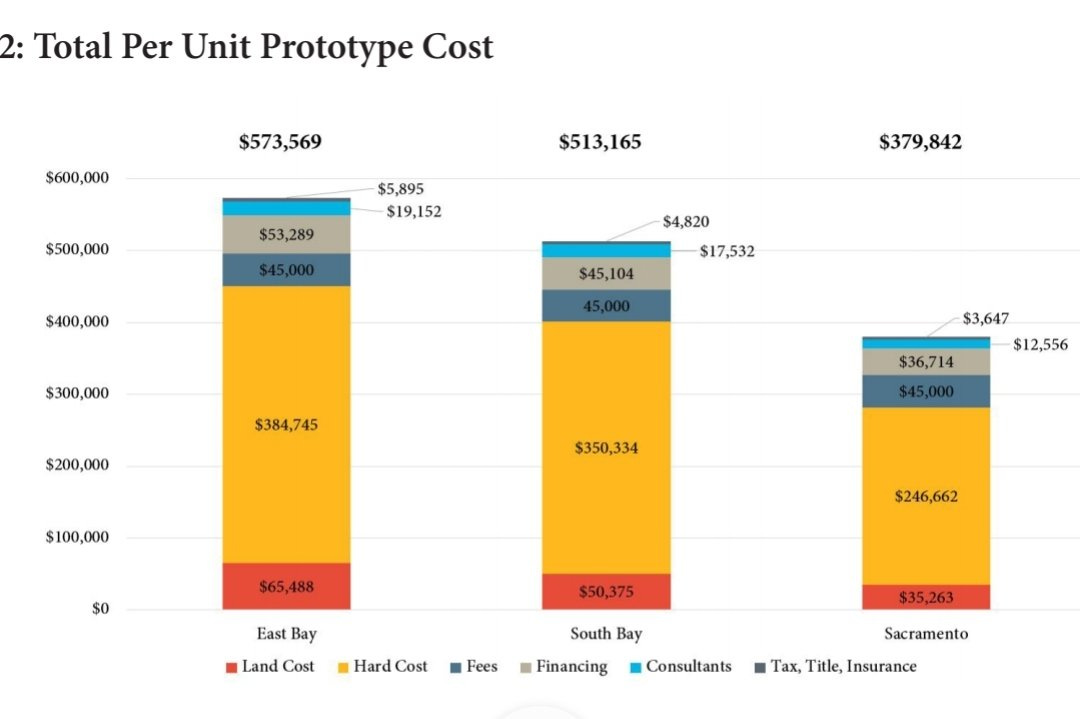

UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation does a lot of work explaining housing finance. In their report on construction costs, things like land costs are only contributing 12% of total project costs and can’t be blamed for high construction costs. In their model assuming 0 affordable housing requirements and 0 environmental mitigation, your average East Bay housing unit will cost $570,000 to build. That’s the bare minimum before additional soft costs are imposed, and each additional cost pushes that $573,000 minimum sale or rental value further up.

Something’s seriously wrong with the construction market nationwide. But note that if East Bay per unit cost are reaching $1 million for subsidized developments, that gap between $573,569 and $1 million is entirely being filled by excessive administrative delays, zoning and permitting costs.

So the problem with terms like affordable housing is that the prices people are asking for is often well below the cost of construction before profit’s even considered. The only way you can provide housing at a cost below its operational and construction costs, is through public subsidies and a cap rents through a law or deed. Or in the case of inclusionary units in market-rate housing developments, by relying on high rent unregulated units to subsidize rents lower in the inclusionary, deed-restricted ones. Inclusionary only works in expensive rental markets.

Failure to reconcile this often leads activists to propose housing policies that make housing more unaffordable to build. Berkeley last year produced housing per-capita at twice the rate of San Francisco. Why? Because San Francisco set even higher inclusionary requirements exceeding max 10 - 20% norm and a whole series of additional fees that made construction prohibitively expensive. Berkeley stayed steady at 20% affordable tops which is the higher end of what Terner recommends not exceeding. SF’s Controller’s Office predicted it would result in fewer homes built, including affordable ones, and that’s exactly what it did.

Well meaning people hyper-focused on adjusting percentages of new development without looking at the absolute number of affordable homes feasible. A higher percentage of a smaller quantity is fewer over all. Homes prices are set on what the market will bear, and if production costs exceed market prices, no one builds. High construction costs and zoning limited land in places like SF means the only housing that exceeds costs and profit is high end, expensive, A-class units and demand for it isn't that high. (These are normative statements about markets, not prescriptive, to be clear.)

Nevertheless, this is why I’ve largely abandoned the term “affordable housing” and opt for subsidized housing. The vagueness of the term allows for those who push policies that make housing unaffordable to abstract ideas of cheap housing without committing to the reality that it must be funded. It’s also important for journalists when reporting the share of housing approved that’s affordable vs. not that what they’re really describing is subsidized housing vs. non-subsidized housing.

Plain and simple: High housing costs are indicative of high construction costs. We’re never going to have affordable housing for all if “affordable housing” costs $1 million per home to build. Notably, the among the biggest supporters and sponsors of YIMBY legislation in Sacramento to ease construction costs aren’t real estate groups, but nonprofit subsidized housing development associations who can’t afford these costs any longer.

Next week I’m publishing new Census data analysis as a sequel to my piece “Where Did All The Black People in Oakland Go.” This time it’ll focus on all demographics with key new household data and new interactive maps.

Subscribe for first week access and thank you for reading!

Darrell, this is a perfect explainer! I stopped using the term "affordable housing" about a year ago, and started explaining to people that "affordable housing" means deed-restricted, income-qualified, government-subsidized apartments, not a place that your 30-year old kid could afford to rent. Now I will send them your article. Actually, I won't. I recently moved to pro-housing Santa Rosa after 40 years in Santa Monica. I was partly motivated to leave because I was so tired of explaining this to my friends, neighbors, and even the clerks at the grocery store on a site that is slated for a large mixed-use project. "At least you may be able to rent an apartment in this new building; your union-scale paycheck is too high to qualify you for most affordable housing projects, and an affordable housing project will have to select tenants from a national lottery, not from the neighborhood workforce." GRRRRR.

Great article, as usual. One candidate for the absolute floor on per-bed costs in coastal California is the proposed Munger Hall at UCSB. According to Wikipedia, it's supposed to cost $1.4 billion and house 4,500 people, which is a per-bed cost of around $310,000. This is for a building where 90% of the rooms won't have windows, which would not be considered habitable under any zoning code I've ever heard of. So if that's the cheapest we could *possibly* build, it shouldn't surprise anyone that a humane living space with a window and a toilet is going to cost quite a bit more.